The tiny device that can mean surgical success or failure

A big hospital can spend more than $1 million a year on sutures. A study by the ECRI Institute found there can be big differences in their quality.

It's a safe bet that the vast majority of patients never give a moment's thought to the sutures their hospitals buy. Here's your chance to learn why the threads surgeons use to tie wounds together while they heal are more interesting, important, and costly than even the experts at Plymouth Meeting's ECRI Institute had imagined.

ECRI, which evaluates medical procedures, devices and drugs, decided to look at sutures after officials at a national hospital chain based on the West Coast said they got frequent requests from surgeons to use something other than the types of sutures they had authorized, said David Jamison, executive director of ECRI's health devices group. Many hospitals have tried to reduce costs by buying supplies in bulk and giving individual physicians less choice about items like sutures or orthopedic products.

About two-thirds of hospital spending is not for big-ticket items, but for products such as sutures or caps for intravenous lines that need to be replaced often, Jamison said. Many traditionally have been chosen by physicians. ECRI decided to step into this sector with its suture report, which is available only for purchase. Jamison wouldn't say how much it costs, but said the price tag is in the thousands for non-ECRI members.

The price of sutures themselves varies widely, depending on deals hospitals are able to make with the two dominant suppliers, Medtronic and Johnson & Johnson's Ethicon division. But the cost of those little threads can really add up. ECRI estimates that annual spending for sutures is $51,000 for a small hospital, $320,000 for a mid-size hospital, and $1.3 million for a large one.

Jamison said problems with sutures have been tied to patient complications and deaths that ECRI has investigated, though there are no broad studies comparing how suture quality affects patient outcomes.

Sutures come in a variety of sizes, shapes, and colors. Many are meant to be absorbed into the body at different rates, depending on the nature of the wound or incision. Increasingly, some are barbed, so that surgeons don't have to knot the suture when they are done sewing. Most come with curved needles of various types already attached. ECRI also tested needles, because surgeons complained that some got too dull after several cuts. Some sutures are braided. Some have a single filament. They can be made of collagen, silk, or polymer.

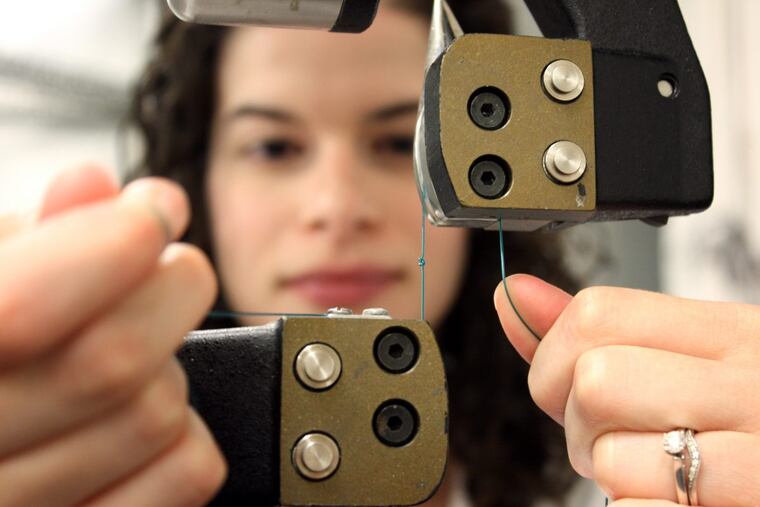

Julie Miller, a project engineer, was in charge of testing 32 product lines of sutures and four kinds of needles. ECRI did not analyze how sutures performed in patients or test them in animal tissue. Miller based her inquiry on what surgeons told her was important to them: suture strength, how well knots held, needle strength and sharpness, and "out-of-package memory," a measure of how easily a suture straightens out after it's removed from packaging. She measured strength both when sutures were fresh and after they had been in a environment meant to simulate the body. The testing detected significant differences in strength and knot slippage, which could affect bleeding. "We did find that some [sutures] were more slippery than others, and the knot did fail," Miller said.

Jamison said the research basically showed that the surgeons were right. Suture performance could vary across brands, with one type within a brand being superior while others were not. For example, Medtronic's Polysorb, a braided midterm absorbable suture, was stronger than its direct competitor, while Ethicon's Chromic Gut, an absorbable collagen suture, was stronger than its competing product line.

"The supply chain people thought the surgeons were just complaining, but it turns out they were valid in some of the comments," Jamison said.

Will this information save hospitals money or cost them more? ECRI didn't look at that. Jamison said an analysis would have to look beyond just the cost of the sutures. Surgeons, he said, would want to factor in the impact on surgical complications or wound healing.

Many surgical patients get both sutures and staples. ECRI will look at staples next year.