A father's crusade against steroids

Don Hooton's son killed himself after using drugs to bulk up. Hooton grieved - and then decided to fight.

Don Hooton had just finished telling Congress how steroids had driven his teenage son to suicide. As he gathered his emotions in a dark corridor of the Rayburn House Office Building, a baseball owner approached.

"He said, 'I wasn't in that room today, but I was watching on TV,' " recalled Hooton, who did not want to identify the owner. " 'I want to tell you how sorry I am for what happened to your son. But you need to know that you changed Major League Baseball forever today. We're committed now to seeing that this problem gets taken care of.' "

Despite the superstar witnesses who also appeared at the House Committee on Government Reform's recent hearing on steroid abuse in baseball, it was Don Hooton's passionate account of his drug-damaged son's death that has had the most immediate impact.

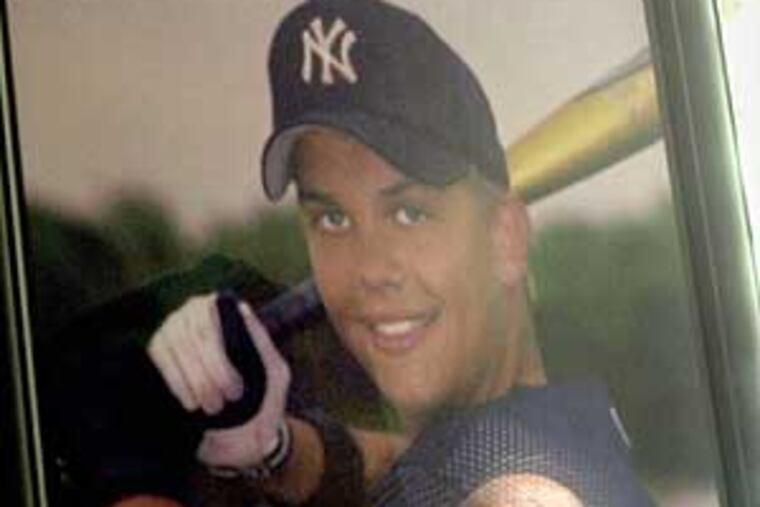

Taylor Hooton, a steroid-swollen 17-year-old high school baseball player who had grown up in Montgomery County dreaming of a big-league career, hanged himself in his Texas bedroom on July 15, 2003, not long after a coach told him he needed to get bigger.

The emotional March 17 testimony by Hooton, who had lived for 12 years in Lower Gwynedd Township and Lawrenceville, N.J., before relocating to Texas in 1999, instantly motivated not just baseball owners, but players, politicians and physicians as well.

Curt Schilling and Frank Thomas asked him to work with Zero Tolerance, their anti-steroid education effort. The American Academy of Pediatric Physicians invited him to speak before 10,000 members at its September convention. The California Senate, considering steroid-related legislation, had him testify. And his Taylor Hooton Foundation, which received its 501C3 status as a tax-exempt public charity that same week, has been deluged with offers of assistance.

"The response has been overwhelming, and I'd say 95 percent of it has been positive," said Hooton, a marketing executive with Hewlett-Packard who, along with his wife and three children, spent six years in Lower Gwynedd during the 1990s. "But, frankly, we've gotten some e-mails, always anonymous, that want to blame us or something other than steroids for Taylor's death.

"I tell them that 60 Minutes, the New York Times, and plenty of other people have done thorough investigations into the case. If there was anything else wrong, somebody would have ferreted it out. It was the steroids."

Taylor Hooton and his older brother, Donald, were in love with baseball when they lived in the Philadelphia area. The attraction was genetic.

Their father's first cousin was Burt Hooton, the ex-big-league pitcher whose 15-year career included two memorable events in games against the Phillies - throwing a no-hitter in 1972 as a Chicago Cub, and being booed off the mound as a Los Angeles Dodger during a 1977 playoff game at Veterans Stadium.

"I can't tell you how many people, when we lived in the Philadelphia area, told me the story about him being booed," said Hooton, who at the time was vice president of sales and marketing for Ulticom, a telecom software company based in Mount Laurel, Burlington County.

As a high school senior in 1999, Donald, a righthanded pitcher, was The Inquirer's player of the year for Bucks and Montgomery Counties. He helped Wissahickon High win the Suburban One League's Freedom Division title, compiling a 5-1 record with a 1.71 ERA and 70 strikeouts in 45 innings.

Taylor, meanwhile, played Little League ball in Montgomery County and was 13 when his family moved to Plano, an affluent Dallas suburb.

It was there, as a junior-varsity player for Plano West High School, that the 16-year-old got the message that ultimately led to his death. A junior-varsity coach told him and another player that if they wanted to make next year's varsity, they had better get bigger and stronger.

In the months that followed, his parents grew concerned. The slightly built Taylor had bulked up, from 170 to 205 pounds. He had developed other telltale signs of steroid abuse that they didn't recognize at the time - acne on his back, irritability, aggressive behavior, and wild mood swings. He became belligerent and on at least one occasion withdrew money from his parents' bank account without permission.

Suspecting drug use, they had a family doctor administer two tests. Donald, who went on to pitch for the University of Louisiana at Lafayette, the University of Texas at Arlington, and Gwynedd-Mercy College, from which he graduated in May, suspected that his brother might be using steroids and told his parents. Meanwhile, because the drug tests were not designed to detect steroids, the results came back clean.

"We took him to the doctor twice, and when his behavior didn't clear up, we took him to a psychiatrist," Hooton said. "What else is a damn parent supposed to do? It was during his sixth meeting with a psychiatrist that he admitted he was doing steroids. And when she asked him why, he explained to her" the junior-varsity coach's comments.

The example of that coach and his advice, innocent or not, is what Don and Donald Hooton convey to the high school athletes, coaches, physicians and parents they encounter through their foundation's work.

"We tell them, 'Guys, what was acceptable behavior 10 years ago borders on negligible behavior today,' " Hooton said. "You can't just tell a 16-year-old kid that he needs to get bigger and then leave him to his own devices to figure out what that means - especially when you find out, as we later did, that close to half the kids on that team were using steroids."

Taylor's behavior continued to worsen in the last months of his life, even as he told his parents he had stopped injecting Deca 3000 and taking Anadrol pills, some of which he was obtaining illegally from Mexican sources. He punched a hole in a bedroom wall, beat up the boyfriend of a girl he knew, and flew into frequent rages.

It was after his parents grounded him one weekend that Taylor fastened a knot from his belt and hanged himself from his bedroom door.

The foundation named for him grew out of a meeting at Plano West, just weeks after the suicide. More than 600 people turned out to hear the account of Don Hooton.

"The Dallas Morning News covered that event, and the rest is history," he said.

With Hooton as chairman and his surviving son as president, the foundation has spread its anti-steroid message across the country, primarily through high-school seminars.

"People need to be educated," Hooton said. "A paper down here did an investigation into steroid use among Texas high school athletes, and there were coaches who said things like, 'I've been a coach for 22 years and I've never seen any steroid use.'

"Well, in today's environment, they ought to be fired. That's a ridiculous and irresponsible statement. These coaches need to be trained what to look for. Otherwise, they're going to be sending these kids naively back into that environment. And then what do you expect the kids to do?"