Project would restore historic Jewish site

But N.J. plan faces opposition

PITTSGROVE TOWNSHIP, N.J. - One recent morning, turkey vultures soared above the open fields and two-lane country roads of this rural patch of Salem County. Rusted tractors slept beside sun-bleached barns, dusty corner stores longed for customers and abandoned houses stood defiantly against advancing vegetation.

"The area looks more like North Carolina than New Jersey," said Norman Lenchitz, who lives at the end of a long driveway on Crow Pond Road.

Although some people might be surprised to find such tranquility in the nation's most densely populated state, Lenchitz' surprise when he relocated here from North Jersey had more to do with his discovery of the area's deep ties to Judaism.

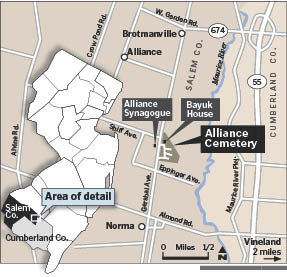

"I was camping here in the late '70s, and when I was riding bikes I saw Hebrew letters out here," Lenchitz said of the meticulously maintained Alliance Cemetery, on Gershal Avenue. "I wondered: What are the Hebrew letters all about?"

Last week, the Garden State Preservation Trust ratified and sent to the legislature a recommendation to fund a project that could help the Jewish Federation of Cumberland County spread the word about those Hebrew letters, the cemetery and synagogue they adorn, and the 42 families that fled the Russian pogroms of the late 1800s to start the Alliance Colony, one of the first Jewish agricultural settlements in the U.S.

The federation, which represents Jewish activites in Cumberland and Salem counties, would get more than $400,000 to restore the brick house that once belonged to Moshe Bayuk, an Eastern European-born lawyer, Jewish scholar and farmer whose sons founded Phillies Cigars and invented a pop-culture icon, the Phillies Blunt.

Bayuk, who died in 1932, is buried about 50 yards from the house, amid the juniper in the Alliance Cemetery. Across the street is the historic Alliance Synagogue, a simple chapel that still houses a small congregation. Another $50,000 in state funding would go toward making Bayuk's house the headquarters of the Alliance Heritage Center.

A second and more ambitious phase of the federation's project could cost almost $4 million, according to Kirk Wisemayer, the federation's executive director.

It includes moving two dilapidated and abandoned synagogues - Beth Israel, on Garton Road, in Deerfield Township, Cumberland County; and Crown of Israel, on Centerton Road, in Monroeville, Salem County - and resettling them, refurbished, in front of the Alliance Cemetery.

"Eight years ago, there were 11 such structures in the area; today there are five," said Wisemayer, a Canadian who grew up in Australia and now lives in Vineland.

But even though the neat and well-kept Alliance Synagogue would be restored to its original condition in the first phase of the project, not all of its members have been won over.

'A stupid idea'

'A stupid idea'

When Stu Cohen, 47, visits Alliance Cemetery, it takes a while for him to pay tribute to relatives and loved ones: He visits two dozen graves, from his parents and grandparents to old friends.

Cohen, a lifelong Vineland resident and a member of Alliance Synagogue - where his father, Bernard, was a leading congregant - sees the federation's plan as nothing more than a power grab.

"I think it's a stupid idea; I think they're being totally greedy," he said of the federation. "All these outsiders want to come in and take over, when the previous 50 years they wanted nothing to do with us. I'm all for preserving culture, but I think it's already preserved just fine."

The synagogue's treasurer, Lenchitz, had wondered whether the small congregation would give up sovereignty, or whether its bucolic setting, where generations of immigrant farmers are buried, would irrevocably morph into a theme park.

Lenchitz, 51, who is also a member of the cemetery association board, pondered these questions in a recent congregation newsletter. But after meeting with Wisemayer last week, he believes that the advantages appear to outweigh the disadvantages.

"We felt that things were spinning out of control, but it's not the case," he said. "We're just overly cautious if we hear things starting to change.

"If it goes off as planned, it could be a very historic place to visit. It could be the Williamsburg of South Jersey, not the Disneyland as some people thought it might be."

Jacob Small, 79, a retired Vineland pharmacist who grew up in Alliance - his father, "Julius the Barber," cut hair and gave dancing lessons for decades at Gershal Avenue and Almond Road - said that the project's price tag concerns him.

"That's the one thing I can't make up my mind about," said Small, whose parents and friends are buried in the cemetery. "To spend a lot of money to move old buildings, I just don't know."

Roots in persecution

The origins of the Alliance Colony date to the late 19th century, when Jews in what is now Ukraine were being massacred in Czarist pogroms.

In 1882, the German-Jewish philanthropist Baron Maurice de Hirsch and the Paris-based Alliance Israelite Universelle - for which the colony was named - paved the way for 42 settlers to seek out a quieter, albeit difficult life by tilling the soil instead of fighting it out among the masses in squalid, inner-city tenements.

"There was a belief that the Jews had to return to the land," said Wisemayer, 47.

In the communities of Pittsgrove Township - Alliance, Brotmanville, Norma, Six Points - the immigrants also experienced something more alien than agriculture: acceptance.

"They were in an area that was rural and affordable, and they had friendly neighbors," Wisemayer said. "There were two Christian families who helped them with their land and allowed them to work on their farms."

Most of the Alliance immigrants were subsistence farmers who grew produce and raised chickens, and who worked off-season in local cranberry bogs and clothing factories, he said.

As the decades passed, the Jewish community spread from the small homes of the Alliance Colony to nearby Vineland, where the Jewish population had risen to almost 12,000 after World War II, Wisemayer said.

Today, that number is down to 1,100 in all of Salem and Cumberland counties.

"People moved away from agriculture beginning late '50s and '60s, partly by their own desire," said Wisemayer. "Most of their parents still live here. We had three funerals this week."

Family ties

U.S. District Judge Stanley S. Brotman's father and grandfather are buried in Alliance, and his family name is on the Brotmanville sign at the Route 55 exit that takes motorists to the area.

Brotman, who splits time on the bench in both Camden and the U.S. Virgin Islands, said that he supports any cause that would shed light on all the names whose roots were planted in the South Jersey Jewish experience.

"So many families had their start in that area," he told the Daily News by phone from the Virgin Islands. "It should be given the historical significance it deserves."

Vineland lawyer Jay Green-blatt said that his father, who was a carpenter and butcher in the Alliance Colony, is buried in the cemetery, which he said gets visitors from throughout the U.S. He said that a heritage center would be a fitting voice for the dead.

"It might be centered on Alliance, but it's something for the entire area to take part in," he said. "It's quite a story. I don't think too many people are aware of it."

On this winter morning, no schoolchildren nervously eyed the cemetery gates, no buses unloaded camera-toting tourists. The historic acres were silent, except for the occasional oil truck grumbling past and the flapping of a gray tarpaulin against the roof of the Bayuk house.

Keeping watch over the generations of Jewish farmers were piles of pebbles, neatly placed atop the grave markers by loved ones who had made the trek down these scenic roads.

For more information, visit http://alliancecemetery.com