Father continues fight for custody of son

TWENTY-eight-year-old Kirtis Golden wants to be a single dad. He isn't thinking about fathering souls he's yet to meet or faces he's yet to see.

TWENTY-eight-year-old Kirtis Golden wants to be a single dad.

He isn't thinking about fathering souls he's yet to meet or faces he's yet to see.

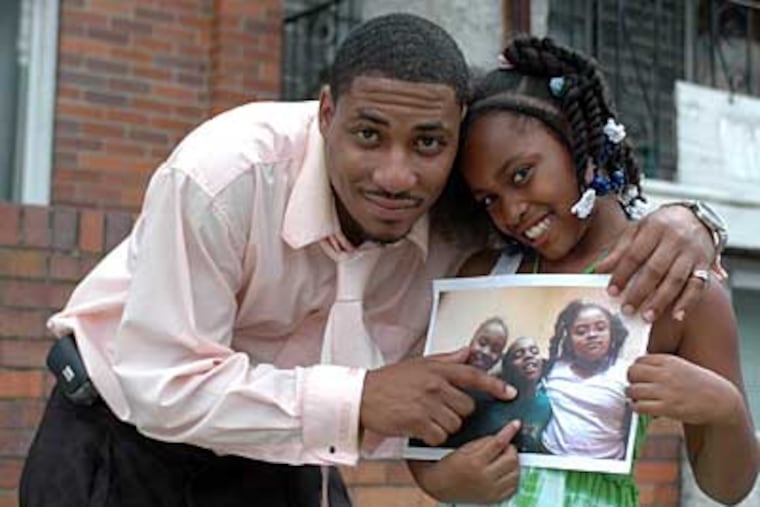

Golden wants to be a dad to his own son and daughter - and for seven years he's been fighting to do what so many men don't fight for at all.

It was only in April, when a family-court judge awarded Golden full custody of his daughter, 9-year-old Kameara, that he was able to start being the type of father that would have made his dad proud.

But Golden's 7-year-old son, Keream, remains in the care of the Department of Human Services, and Golden said that the agency is attempting to terminate his parental rights and put the boy up for adoption.

"I'm here screaming 'Give him to me! Give him to me!' " Golden said. "I could understand if I was this hoodlum and I had a rap sheet the size of Broad Street and I didn't have morals, values, ambitions or goals, but that's not the case."

But, according to DHS, a clean record, a house in West Philadelphia and a steady job just aren't enough.

The agency said that Golden hasn't kept required biweekly visits with his son and, despite the fact that he's begging to parent Keream full-time, the missed visits could result in the boy's adoption.

"I don't see the justification," said Golden's elder brother, Kendall. "If he hasn't visited enough, wanting full custody goes beyond visiting."

Golden admits that he hasn't been to see his son since he dropped him off about a year ago at a behavioral-health facility in Langhorne, as required by DHS.

Keream, who has been in foster care since he was 6 months old, was ordered to the facility because he was acting like an animal - literally.

"He wanted to portray a cat or dog," Golden said. He then surmised, "That shows me he lacks the love and attention he needs and wants."

Although he talks to Keream on the phone, Golden said that he's so "devastated" about where Keream has ended up that he doesn't want to see his son, or his son to see him, "under those circumstances and conditions."

"Every time I think about it, it makes me sick to my stomach," he said.

Golden also said that his ever-rotating shift at Temple University Hospital - where he transports patients to various wings for testing - his recent health issues and a lack of transportation have compounded his troubles.

DHS spokeswoman Donna Wyche said that all parents are fully informed of the visitation requirements, and that DHS not only provides transportation for visits, but also picks up the cost.

Golden denies that he was ever offered transportation.

"We have one whole unit, that's all they do - order train tickets, bus tickets and hotels," Wyche said. "Visitation is definitely an integral part. The court is basically looking at the relationship between the parent and the child and that has to start with them seeing each other."

Citing confidentiality, Wyche said that she could speak only in generalizations and not specifics of the case, but she said that even if a parent expresses a strong desire to be involved in a child's life, visitation is key.

"Everything, from school to the work that we do, it's not based on what you're saying, it's based upon your actions," she said.

Golden said that his children were living with their mother when they were taken out of her care by DHS in 2002 because she was not providing them proper medical treatment.

Keream was 6 months old and Kameara was 2 years old when their mother relinquished her rights, Golden said, though DHS could not confirm that statement.

Initially, the kids were placed in Golden's temporary custody and lived with him at his mother's house. But within two months, DHS removed them from his care because he didn't get them their immunizations in a timely manner, he said.

In the seven years following, the children were separated and placed in a total of 12 foster homes, Golden said.

Throughout those years, Golden said, he tried to get both children back. He held down jobs, kept a home, visited the kids on weekends and attended required Family Therapy Treatment.

In a November 2007 letter from Family Therapy Treatment counselor Diana Kochan, provided to the Daily News by Golden, she writes, in part:

"Kirtis, your ability to overcome the various obstacles that you have encountered on your path to bringing your family together taught me what a father's love looks like. The amount of resilience and strength that your family possesses provides a sense of hope to those that come into contact with you."

Golden said he not only attended the required treatment with his family but also passed two psychological evaluations with "excellent" marks.

Coming from a family with 13 siblings, Golden said that parental responsibility was instilled in him by his father, a city firefighter, and his mother, a teacher.

"I understand the value of family," he said. "I understand how it's pivotal to long-term success because, ultimately, it gives you a sense of accountability.

"I want to be the man my dad showed me to be," he said.

Golden's older brother, Kendall, 44, who raised six children himself as a single dad, has watched his brother jump through "hoop and fire" to get his kids.

"It was not by design, but the men of this family have stepped up to the responsibilities of fatherhood," he said. "We set standards and expectations, not only for our children, but ourselves."

Phil Lafosse, a minister at Calvary Baptist Church, on Haverford Avenue near North Robinson Street, where Golden attends, has counseled him through his travails. Lafosse said that Golden has been sincere, mature and resilient in his struggles.

"Unfortunately, I told him it looked like he was stuck in an environment and in a system that was so not used to seeing someone doing what he was doing - trying so hard," he said.

Lafosse said that Golden and his daughter come to church every week. The first time he brought her after winning custody, she was so happy to be by his side that she didn't want to leave to attend a separate, children's church, Lafosse said.

"Those are the moments you wish you could document and show to DHS," he said. "Because things on paper don't always make the best proof."

But Wyche said that state mandates require the appropriate paperwork documenting visitation and the like.

"A social worker may believe you love your kid, however, there are things you have to do," she said. "It can't be based on me going into court and saying you love your kid.

"It's not a secret. It's clearly written out that these documents need to be signed," she said. "Sometimes parents just can't do it for a variety of reasons, but it's not due to lack of knowledge."

Golden's love for his children is evident. He keeps a clean house, replete with religious paintings, family photos and plants, and is stern, yet kind, with Kameara, who remembers far too well the last seven years before she lived with her dad.

"I was away from home," she said. "I cried every time my dad had to bring me back to foster care. I was so happy when I got to move back in with Daddy."

Kameara, a fashionable and articulate 9-year-old, enjoys going on vacations and shopping with her dad.

She spontaneously bursts into dance while talking about a class she will take this fall, and spontaneously kisses her father when they talk of the dog they will buy after she proves herself in school this year.

There's just one thing missing.

"I want my brother home," she said. "So that way he can stay with us and we can be a family.

"And he can help me walk our dog."

Golden smiled before his voice trailed off. He said that he envisions classes for his son, too - perhaps drum lessons - and sports, maybe football.

But all he can do now is worry what will happen if he never gets the chance to be the father his son deserves.

"I'm so scared if I don't get him things will get worse," he said. "I'm scared he won't have a sense of what it takes to be in a family."