N.J. leaders lack an appetite for double-dipping reform

Double-dipping is so sweet that New Jersey public officials have little appetite for reform.

So despite the sour taste for taxpayers, the legacy of governmental retirees who collect a state pension – then return to public payrolls for a second check – will continue into 2014 and likely for years to come.

New Jersey Watchdog investigations this year found:

• Eighty State Police retirees were rehired by the state, but continued to receive their pensions. Collectively, they received $12.8 million a year – nearly $7 million a year in salaries, plus $5.8 million in retirement pay.

• Seventeen county sheriffs and 29 undersheriffs also double-dip. Together, the 46 top cops raked in $8.3 million a year – $3.4 million from pensions and $4.9 million in salaries.

• Forty-five retired school superintendents returned to work as interim superintendents during the past school year. In addition to their executive pay, they used a loophole in state law to pocket more than $4 million from pensions.

Even though state pension funds face a $47 billion shortfall, New Jersey authorities have never tried to keep tabs on double-dipping or calculate how much it costs. In the State Legislature, 18 double-dipping lawmakers and their colleagues stand in the way of any attempt at reform.

The biggest dipper in the Legislature is Sen. Fred Madden, D-Turnersville, who collects nearly a quarter-million dollars a year from two public jobs and a state pension. In addition to $49,000 in legislative pay, the Senate Labor Committee chairman receives $85,272 from a State Police pension and $111,578 as dean of Law & Justice at Gloucester County College.

"Obviously, I don't have a problem with people doing it," Madden told New Jersey Watchdog last year.

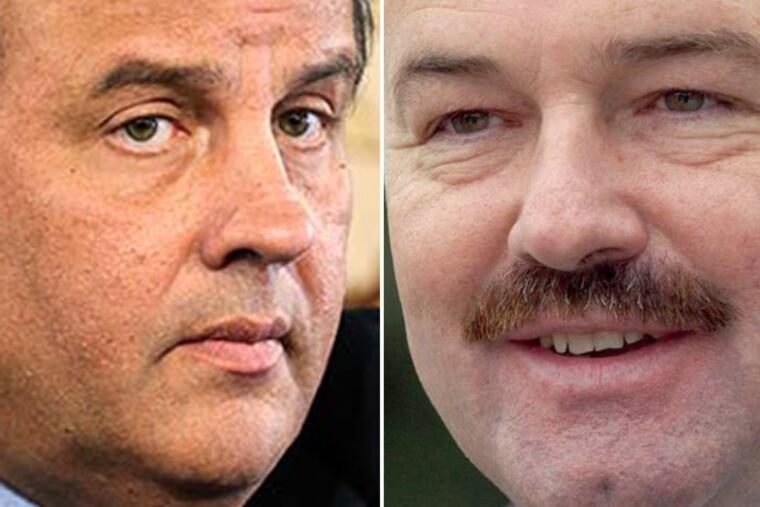

Don't expect Gov. Chris Christie to ride to the rescue.

Christie's deputy chief of staff, Louis Goetting, gets $228,860 a year — $140,000 in salary plus an $88,860 pension as a state retiree.

"The governor called him out of retirement," explained spokesman Michael Drewniak. "And we are grateful to have him."

Not everyone is grateful that double-dipping is such a widespread practice in New Jersey. "It's not appropriate," said Sen. Jennifer Beck, R-Red Bank, one of the few legislators to openly oppose double-dipping.

"The pension system is intended to support you at a time you are no longer working. So when you are an active employee, you should not be able to tap into both."

A reform proposal co-sponsored by Beck could end double-dipping in New Jersey. If enacted, Senate Bill 601 would suspend state pension payments to retirees who return to public jobs that pay more than $15,000 a year. Their retirement benefits would resume when they permanently leave public employment.

Predictably, the measure has failed to reach the floor for a vote. It has been trapped in the Senate's State Government Committee since it was first introduced in February 2011 by Beck and Sen. Steven Oroho, R-Sparta.

During the legislative process, Treasury informed lawmakers that the agency had "no estimate" of the extent or cost of double-dipping.

The lingering question is whether Christie's bean counters were lazy, less than forthcoming, politically motivated or all of the above.

In an effort to determine how easy or difficult it would be for Treasury to track double-dipping, New Jersey Watchdog requested the records that show how the agency keeps its payroll and pension payment records. Treasury denied the request, claiming its records of records are "not government records" and that release of the documents could jeopardize the security of state computers.

In response, a New Jersey Watchdog reporter filed a suit in Mercer County Superior Court. The case is pending before Judge Mary C. Jacobson. Meanwhile, the state's pension deficit continues to grow, as double-dippers tap into their pensions years, and sometimes decades before their retirements were anticipated by actuaries.

"You just can't afford to do this stuff," said Beck. "We're not going to be able to afford to allow people to collect a pension while working full-time. You're really destroying the fabric of the pension system."

The New Jersey Watchdog is a public interest journalism project dedicated to promoting open, transparent, and accountable state government by reporting on the activities of agencies, bureaucracies, and politicians in the state of New Jersey. It is funded by the Franklin Center for Government and Public Integrity, a libertarian nonprofit organization.

Contact reporter Mark Lagerkvist at Mark@Lagerkvist.net