A&E intervenes to rescue ex-boxing champ

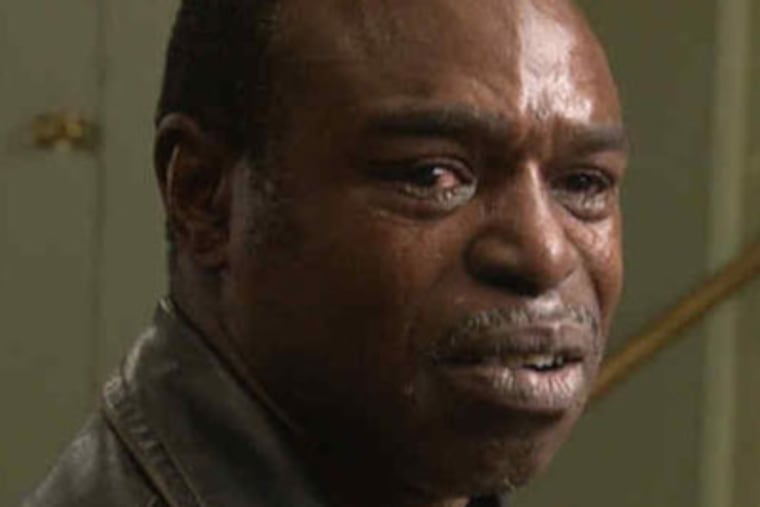

ROCKY was always just a nickname, but it came to represent a broken-down champion who lost his family and more than a decade of his life to crack and alcohol on the Camden streets.

ROCKY was always just a nickname, but it came to represent a broken-down champion who lost his family and more than a decade of his life to crack and alcohol on the Camden streets.

But, with the simple change of one letter, former two-time world boxing champion Rocky Lockridge, 51, is Ricky again, a man from Tacoma, Wash., struggling with sobriety and trying to reclaim his lost years.

"The thing is, when he was out on the streets, all those people called him 'Rocky' or 'the champ,' but he didn't feel that way. He didn't feel like a champ at all," said Bobby Toney, an Audubon, Camden County, man who helped pull Lockridge off the streets last year. "Now he's just going to be a man again, Ricky L. He's going to be a new man, one day at a time."

Monday night, Lockridge's story will be chronicled on the A&E program "Intervention," an Emmy-winning reality series that follows addicts through their daily lives and ends with an intervention involving family and friends.

The addicts are faced with a choice: to continue destroying their lives, or to get on a plane to a treatment facility. Most accept the plane ticket.

Lockridge, who lived in Mount Laurel during his peak years as a boxer, is now living in Louisiana after spending 90 days in a treatment center. He could not be reached for comment. His family said he's staying clean and trying to get Social Security benefits and disability payments he's never received.

"He's been sober for over four months now," said son Ricky Lockridge Jr.

Fighting out of Tacoma as a youth, Lockridge won a national amateur championship and a Golden Gloves title before turning pro. In 1984, he was scheduled as a tune-up fight for the World Boxing Association's super-featherweight champ, Roger Mayweather, who was undefeated at the time. Rocky floored Mayweather in the opening round.

"In a stunner, Rocky Lockridge has knocked out Roger Mayweather in Round 1," commentator Marv Albert roared as Lockridge raised his gloved hands in victory.

Lockridge won the International Boxing Federation's super- featherweight title three years later, and retired in 1991 with a record of 44-9 and 36 knockouts. Last year, Lockridge told the Daily News that he had lost most of his winnings to drugs, alcohol and "bad choices," and wasn't equipped to make a living outside of boxing. In 1993, he left his wife and twin sons in Tacoma and moved to Camden.

"I wish I hadn't," Lockridge told the Daily News in August. He has also has a third son, Ramond, with another woman.

On most episodes of "Intervention," addicts are faced with severe consequences from family members: No more money for drugs. No more roof to sleep under. No more phone calls.

But Lockridge had passed that point more than a decade ago, and his family didn't know where he was or whether he was even alive. His three sons had no contact with him.

"Their whole life had a hole in it," said Candy Finnigan, the intervention specialist who handled the case for A&E. "These boys had really suffered."

Last year, Ricky Lockridge Jr., 25, saw his father for the first time in 15 years. He said he was always willing to forgive his dad if he got clean. His twin brother, Lamar, didn't want to see him.

"He took it a lot harder than I did," Ricky Jr. said of his brother. "He put my dad in the back of his mind. It hurt him too much."

For the last decade, Ricky Lockridge replaced his family with a ragged entourage at 7th and Chestnut streets, a notorious intersection in Camden's Bergen Square neighborhood, where many have been shot dead and regulars shuffle aimlessly back and forth between an abandoned storefront and a liquor store across the street.

Despite having had a stroke and having spent some nights behind bars, Lockridge has managed to survive, hobbling about Camden on his four-pronged cane, because those fumes of fame still left some folks a little awestruck.

"He had a lot longer life as an addict because there was always someone willing to help him out and give him a little money," said Finnigan.

Eventually, another entourage found Lockridge, folks like Bobby Toney and Camden mail carrier Orlando Pettigrew, who admired Lockridge's boxing pedigree but who were concerned about his future.

"I think he had just given up. He had given up on himself and thought everybody else had given up on him," said Pettigrew, who gave Lockridge food and clothes and helped contact Ricky Jr. last year. "I'm keeping my fingers crossed."

The road to "Intervention" wouldn't have been possible without the Retired Boxers Foundation and its executive director Jacquie Richardson, a woman who fights for athletes like Lockridge long after the sport they loved has left them behind. She was the one who contacted A&E for help.

"It's on Rocky now," said Richardson. "He needs to make the best with the life he has now."

Richardson said she'd like to see Lockridge find a "good woman" or get a little storefront with a few heavy bags in it. She doesn't want him to go back to Camden, ever.

"I don't think he would last too long out there again," she said.

Ricky Lockridge's "Intervention" episode will air at 9 p.m. Monday on A&E. For more information, visit www.aetv.com/ intervention.

For more information about the Retired Boxers Foundation, visit www.retiredboxers.org.