How a Philly author predicted Trump's win: Drinking in dive bars

His new book is a travelogue of the most deeply disinvested parts of this country, told from the window seats of cross-country Greyhound buses and over day trips to struggling towns and cities across greater Philadelphia.

In the aftermath of Donald Trump's election victory, pundits, pollsters, and political reporters were left wondering how they had failed to see it coming — and to comprehend the simmering frustration of poor folks around the country who helped put Trump in office.

One person who called it, though, was Linh Dinh. The South Philadelphia writer and photographer has, over the last several years, become a premier chronicler of American decline. His new book, Postcards from the End of America (Seven Stories Press), is a travelogue of the desperation gripping some of the most deeply disinvested parts of this country, told from the window seats of cross-country Greyhound buses and over day trips to struggling towns and cities across this region. His cast includes a Senegalese man selling body oils on the street in Camden, a man whose paltry retirement income provides him just enough to drink himself to death in Riverside, N.J., a woman dying of cancer in Bensalem, and day-drinkers and addicts from Trenton to Chester.

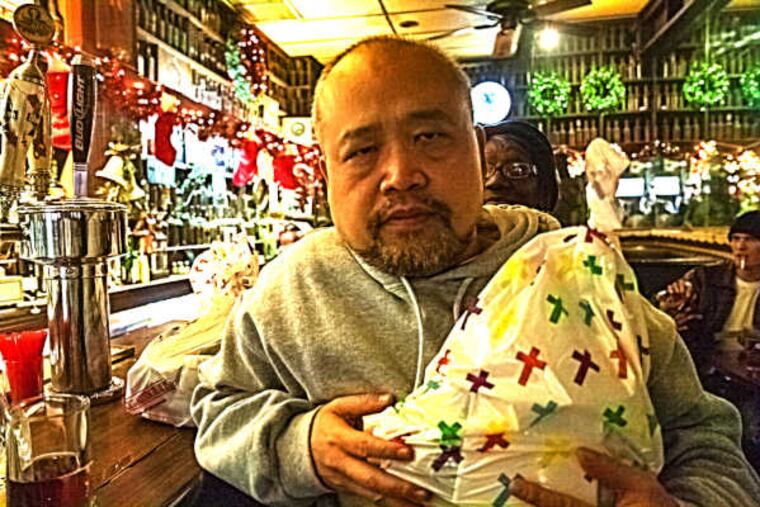

The poet laureate of dive bars, Dinh prefers the view from the bottom, where, he figures, people are at least honest. Dinh, 53, came to the United States as a refugee from Vietnam at age 11, and worked over the years as a house cleaner, window washer, and house painter. We met up in Jack's Famous Bar, at Kensington and Allegheny Avenues near the heart of Philadelphia's opioid crisis, to talk about his "postcards," the social value of dive bars, the rise of Trump, and the end of America.

You didn't grow up in Philly. What keeps you here?

It's cheap, for one. I like the people. And I like to drink beer. That's how you meet people. That's how you talk to people. This bar scene is unusual. Most cities don't have neighborhood bars to the same degree we have. Certainly not New York. I worked in D.C. for a while, and I couldn't even find a bar to hang out. I couldn't find regular people.

Much of your book takes place in 2013 and '14, but it seems to foreshadow Trump's election. How is that?

I saw it coming. I insisted he was going to win. Because when you talk to these people, there's a lot of frustration, a lot of anger, a lot of sadness. Look at this neighborhood. It used to be thriving. The reason this bar opens so early is there used to be three shifts. There used to be factories. This neighborhood was an industrial neighborhood.

I'm not saying Trump's going to do anything. But you can see why people yearn for those promises. They want dignified jobs, and they're not getting it. If you're a young man in Kensington, what are you going to do? It used to be a working-class, blue-collar guy could work with his muscles. There are no more jobs like that, and that's true all over the city.

You traveled all over the country for this book. What surprised you?

Nothing, really — except when I was in Wolf Point on the Indian reservation. That was a little too much. The level of despair and violence there. I met a guy who raped his daughter, and I met the daughter. A guy who was like my best friend for the few days I was there: He just stabbed somebody, I read in the news. There's a lot of drunken violence there, a lot of accidents. But it doesn't surprise me, because I hear the same stories over and over again.

What do you hope readers will take from this book?

I think at the bottom of society, people know we're in trouble. They know they're making less money, they're working harder. But here's the paradox: People in the intellectual class are the most clueless, because they don't come to places like this. They don't know how to talk to regular people.

They should stop being so condescending and contemptuous of regular people. I even get that complaint against me. But I'm not slumming. These people are my people. Until we have an honest dialog between the different classes, we're not going to go anywhere. I think the division between left and right is also very counterproductive. We have common issues, common problems.

You tell so many of these stories from the vantage point of a bar stool. Why?

Where else do you go to meet people? It's a social space. In most neighborhood bars, people don't go there to get drunk. They go there to talk. Especially poor people. If you're poor, you might not have cable, you might not be able to watch the baseball game at home, so you got to come to the f- bar. My neighborhood bar, Friendly Lounge, for example: There's a homeless guy who comes in, he doesn't drink anything. He just comes to use the bathroom and have a warm place to sit. The owner doesn't kick him out. The owner usually gives him a few bucks in the morning, on the pretext of, 'Can you go buy me a cup of coffee?' But he gives him extra money, very discreet. It protects his pride. People take care of each other.

What gives you hope in all this?

That sense of community. At Friendly Lounge, when a cook got fired for stealing on the job, people lent him money, gave him money, so he won't starve. Sometimes, that homeless guy? An old Vietnam vet brings him frozen meals. You see people helping each other. A bar should be a place where you have emotional, psychological, and even financial support.