What it's like to make art on the front lines of Philly's opioid epidemic

People in the throes of addiction are coming in to work with Mural Arts in Kensington. Now, the question is, what's next?

This is the second in an occasional series on the Kensington Storefront, an art-based intervention on the front lines of Philadelphia's opioid epidemic.

Along Kensington Avenue these days, people are dispensing with the niceties. A man panhandling on a recent Tuesday morning made his pitch, in Sharpie on cardboard, simple and clear: "Dope sick."

Dealers openly sought clients on the sidewalk. Users slouched against walls.

And artist Kathryn Pannepacker stood outside the Kensington Storefront, inviting them all inside. There was air-conditioning in there, she told them, peanut butter and jelly sandwiches in plastic baggies, hot tea and cookies, and a craft project to complete.

The theory of the four-month-old Storefront — a collaboration between Mural Arts Philadelphia, community organizations, and the city Department of Behavioral Health and Intellectual disAbility Services — isn't exactly art therapy, though Mural Arts has done that with people in recovery for years. It's more like art as harm reduction, the same principle that guides needle-exchange programs and safe injection sites.

Now, they're finding out just what that looks like in practice.

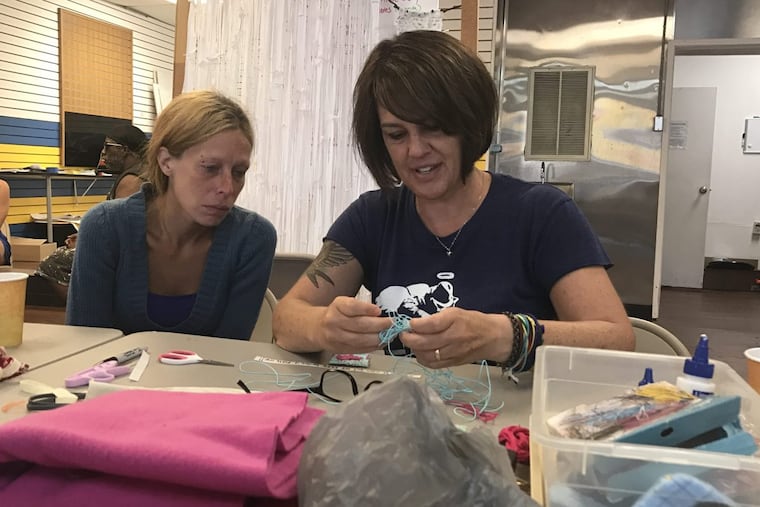

Pannepacker and another artist, Lisa Kelley, teach workshops there on Tuesdays to people recruited off the street and a handful of regulars, mostly retirees from the neighborhood.

On a recent morning, one participant was Holly, a 36-year-old from State College, Pa., who looked exhausted and afraid. She hunched over the morning's project: making a tiny pouch, just big enough to hold a note on a slim strip of paper, like a Chinese restaurant fortune.

Holly, who declined to give her last name, has been sleeping on the sidewalk in Kensington since March. The reason she came into the storefront this morning was simple: "She was really nice," she said of Kelley. "It's a little bit of hope. You need it when you're hopeless and addicted."

Since Holly couldn't steady herself enough to finish her sewing, Kelley helped. Holly said she planned to keep the talisman close, so she could refer back to her note. It read: "I hope I can get off dope before it kills me."

It's just a hope, though.

Kelley, who grew up in Kensington, learned long ago not to bet against the power of addiction.

"Fifteen years ago, my husband and I took in three kids, the children of a friend of mine who struggled with addiction," said Kelley. "Now, all three of those kids have heroin addiction. Often, when it's someone close to you, you don't feel you can do anything to help. So you just do what you can. I thought this was something I could do."

Kelley is incorporating the messages, and others written by people touched by addiction, into a larger weaving project titled Epidemic. "My intention is to make 144 woven panels, which is the number of people that die every day of an overdose," she said.

A few men wandered through the front door. One of the Storefront rules is, anyone is welcome, but to stay you have to participate.

"Would you like a cup of tea?" Pannepacker asked them. "Would you like to join us? It's nice and cool in here."

Across the table, Matt, a 41-year-old man from Northeast Philadelphia who declined to give his last name, fumbled with the sewing project.

"Right now, the future isn't looking too bright, so this little workshop is a way to take my mind off it," he said. "It's nice to be in a safe environment, because you go right out the door and you're surrounded by undesirables and by danger."

He's in a wheelchair, hospital bracelets stacked on his wrists. He was discharged just a week earlier from Temple University Hospital, but he sold his TransPass, so he has no way to get to his follow-up physical therapy appointments.

"Unfortunately, my body is taking a beating. I have pressure sores and, being homeless, it's pretty much impossible for them to heal," he said. His discharge instructions were to keep pressure off the wounds, but sitting in a wheelchair all day makes that impossible.

Matt's been using heroin for more than 20 years; he stays in Kensington because that's where the drugs are. Lately, he said, "I'm finding it harder and harder to function. I feel weaker and weaker."

He wasn't sure whether he'd return to the Storefront. Given that chasing heroin is still his priority, he said, "it's hard to say what's going to happen."

That's the challenge for Mural Arts, said Jane Golden, the organization's executive director.

"People in the throes of addiction are coming in," she said. "But being a drop-in center, that's not something we aspire to. So, what's next? You come into the weaving class, what is the next thing? In this period, we need to struggle with that."

But Laure Biron, program director for Porch Light — Mural Arts' ongoing collaboration with Philadelphia's behavioral health department — believes the workshops are laying important groundwork.

"People need to encounter someone a bunch of times before they feel like, 'OK, you really do care.' People are afraid of service providers," she said. "In the fall, we'll beef up mental health services, because I'm thinking as people come to the space more, we'll build that trust."

In the interim, they're adding other programs: a writing class for teens, workshops on nutrition and financial literacy, housing-related services, expungement clinics. They're also hosting training on administering naloxone, the overdose antidote, and self-care groups for people dealing with the trauma of witnessing overdoses and administering it over and over.

And Golden wants to explore where art can play a role. She's hired a curator to bring quarterly exhibitions to the storefront, and plans on adding new signage, a colorful painted grate, and improved lighting.

"We need to make a visual impact on the corridor," Golden said.

The first manifestation of that is a red, heart-shaped weaving that Pannepacker knotted into a chain-link fence across the street — a small gesture in the face of so much misery.

Just outside the front door of the Storefront, a man sank onto the sidewalk. A few people looked out the window, wondering aloud if they should get out their naloxone kits. Then, an ambulance arrived and EMTs gently guided the man away.

Inside the storefront, most people went back to sewing.

Pannepacker sighed. "This is all the time."