16 schemes lottery legend Joan Ginther likely didn’t use

She probably didn’t crack the scratch lottery code or reverse-engineer a prize-distribution algorithm to win four huge prizes.

Joe Bennett strongly doubts lottery legend Joan Ginther had inside help, as skeptics have suggested.

He shared the number of lottery workers who know where to find unscratched winners in instant games.

"Nobody. Zero," said Bennett, vice president of game development for Scientific Games, which prints instant tickets for almost every state lottery.

And it's been that way for almost a decade.

In 2004, William C. Foreman, a Hoosier Lottery security official, told two men which grocery store had one of the $1 million prizes in $2,000,000 Bonus Spectacular. Foreman, eventually sentenced to eight years of home detention, got the information from a colleague.

The following year – before Ginther won any of her three major scratch-off prizes -- Scientific Games switched to a patented encrypted software system that kicked humans out of the loop.

Nobody can tell if an instant ticket is a winner until it's been scratched off.

"That's really part of my job, to make sure nobody knows," Bennett said.

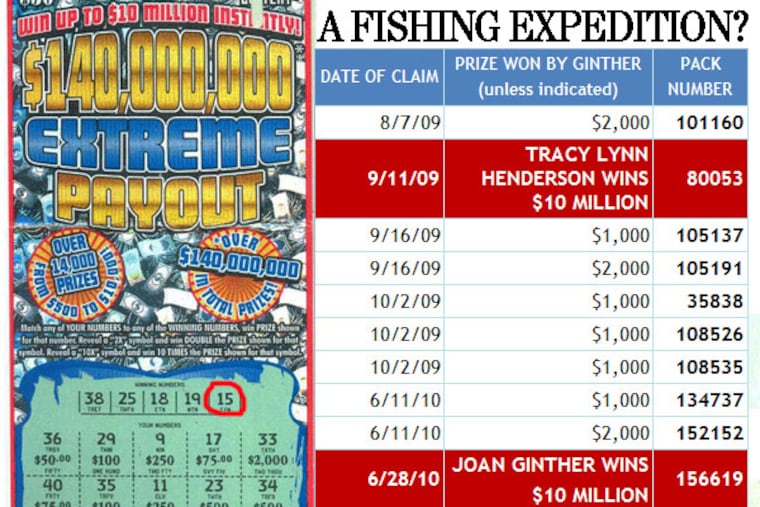

That puts quite a damper on suspicions that Ginther must have had inside help to win four multimillion-dollar lottery prizes, beginning with a $5.4 million annuity from splitting a Lotto Texas jackpot in 1993. Her scratch-off bonanzas were $2 million in 2006, playing Holiday Millionaire, $3 million in 2008, playing Millions & Millions, and $10 million in 2010, playing $140,000,000 Extreme Payout.

Frankly, most theories that Ginther had an ingenious system, from "cracking the lottery code" to high-tech ticket-scanning, wither in the face of scrutiny.

She didn't need to know prize-distribution and shipping patterns to deduce when her last two big instant winners were to arrive at Times Market in her hometown of Bishop. In effect, she made them come to her by buying massive quantities, triggering massive orders. Times Market was No. 1 in sales for $140,000,000 Extreme Payout among the state's 16,000 lottery retailers.

See Part 1: "How lottery legend Joan Ginther bought a flabbergasting number of tickets"

Indeed, months of data-gathering and analysis, often with the help of experts, point more toward a theory based on basic gambling principles: She won mostly because she bought an astonishing number of tickets, and she bought that many tickets at least in part because she realized Texas scratch-offs were among the best bets lotteries ever offer.

See Part 2: "How lottery legend used odds, Uncle Sam to win millions"

Skeptics will always wonder, though, so here's a rundown of theories that, while intriguing, seem to fall short.

A history of cheaters

The Hoosier Lottery scandal is far from the only example of official dishonesty.

There's the famous Triple Six Fix. On April 24, 1980, the Daily Number came up 6-6-6 in Pennsylvania, and an unusual number of winning bets aroused suspicions. The perps apparently injected paint into all the numbers but the 4's and 6's, making them most likely to rise.

In 2002, a security audit of the Maryland Lottery cited an estimated $232,000 worth of instant tickets being "improperly activated over a 15-month period," with at least $112,000 in winning tickets being fraudulently cashed.

More recently, there's the case of the Arkansas lottery official who cashed in 22,710 tickets. Remmele Mazyck collected nearly a half-million dollars from 2009 to 2012 by designating tickets as promotional giveaways, then redeeming them. Mazyck got three years in prison.

It's hard to see any relevance to Ginther. She didn't work for the lottery and wasn't a retailer. People saw her buy a lot of tickets. And what kind of conspiracy calls attention to itself by letting a three-time winner collect another $10 million, triggering headlines around the globe? After that win, she kept right on claiming smaller prizes for two years, suggesting she had nothing to hide. Her friend Anna Morales also openly claimed about two dozen prizes worth $10,000 to $10,000, as well as hundreds of smaller prizes that could have been cashed at retail stores.

Patterns in the prizes?

Perhaps the tickets themselves gave Ginther clues to the whereabouts of winners.

In "The Luckiest Woman on Earth," a 2011 article in Harper's, Nathaniel Rich speculated that Ginther might have deciphered the algorithm, or set of mathematical rules, for how major prizes are seeded in each game, perhaps by analyzing hundreds of tickets. Then, if she had a source of information about shipping patterns, she could predict where winners would land.

We've already shown Ginther didn't need to know shipping routines. Playing repeatedly greatly elevated the odds of winners coming to her town.

Choosing her timing wisely might have helped, however. Say Ginther thought the second of three top prizes tended to show up 60 percent of the way through the game. She could have kept track of remaining prizes by checking the Texas Lottery website or stats in the Lotto Report newsletter published by Dawn Nettles. Ginther could have waited until sales passed 55 percent, say, to start ordering like crazy.

Bennett, head game designer for Scientific Games, dismisses the whole idea she outsmarted any random-number generator (RNG).

"Even if you had a supercomputer and a trillion data points, you still could not predict if the trillionth and one ticket is a winner," he said. "You still wouldn't have enough information to predict the next ticket."

He also dismissed the idea of timing.

"Every game is unique in what we call the shuffle," Bennett said.

Tickets can have tipoffs

Another approach is to find a way to screen tickets. If you could eliminate losers without scratching them off, costs would plummet and playing would turn a profit, even if you never found a top prize.

Mohan Srivastava figured out just such a system, as detailed in Wired Magazine's "Cracking the Scratch Lottery Code." In some games, the Toronto statistician discovered, patterns of symbols printed on the outside of the ticket gave clues as to whether that ticket was likely to yield a prize.

"I remember thinking, 'I'm gonna be rich! I'm gonna plunder the lottery!' " he told Wired. He found retailers who agreed to take back his unscratched rejects, since they didn't believe any such screening was possible. Soon those dreams dissipated. "... I estimated that I could expect to make about $600 a day. That's not bad. But to be honest, I make more as a consultant."

So he spilled the beans to lottery industry officials.

Such a scheme could have funded a sustained search for a colossal payday.

The trick, though, didn't work for the games Ginther won.

"I don't think she used a variation of what I did," Srivastava emailed. "At that time, it couldn't have worked in Texas ... I know because I looked into this specifically, even before I knew anything about Joan Ginther."

Images of tickets from the games she won confirm. All had the same identical sets of symbols on each ticket. No clue-producing patterns. Check out this comparison of an unscratched Holiday Millionaire ticket with Ginther's actual $2 million winner:

Besides, such a scheme would generate a massive number of unscratched losing tickets to foist off on unsuspecting buyers. Folks in Bishop, though, complained about Ginther monopolizing all the tickets for some games, according to Rich. Further, records show Times Market returned no tickets to the lottery at the end of Extreme Payout.

Still, that's not the only scheme for screening tickets.

A light idea

After Ginther's $10 million win made headlines in 2010, an instrumentation expert called the Texas Lottery in 2010 and suggested she used high-intensity light or X-rays to get a sneak peek at hidden layers of symbols.

It's a lottery player's dream. But tickets are printed with extra layers and extensively tested precisely to prevent such attacks, according to lottery officials.

Even during the press run, tickets undergo testing in a lab. "We're subjecting the tickets to heat, to high-intensity light, we're subjecting the tickets to chemicals. We've developed the chemistries and the engineering to prevent those things from happening," Bennett said.

Funky marks

Some players believe that marks might be a tipoff to winning lottery tickets. Problem is, some point to white lines, others to black "alignment marks."

"That's ridiculous. It really is," Bennett said. "... There's no connections between a mark or a color of anything. It's all computer controlled."

It's not like winning tickets are printed separately and shuffled in, resulting in detectably lighter or darker ink. A game could have a million winning tickets and millions of losers, and they're all created with the same layerings and inks, as the presses run off 1,000 feet of tickets every minute, he said. Coloring might vary, but it's not related to any prizes.

"There's nothing in the bar code that offline determines the value," he added.

Post-win shenanigans

The possibilities could continue -- if we wanted a conspiracy theory for a plot twist on TV.

The most common kinds of lottery cheating happen after a winning ticket is found.

Ginther wasn't a store owner, or a retail clerk, so it's hard to see how she'd get involved in strategies like buying tickets after losing streaks, microscratching, cheating customers (like thefts worth $12.5 million and $5.7 million in Ontario, $5 million in Syracuse, $1 million on Long Island, and $1 million in Texas) or bootlegging U.S. tickets in foreign countries.

In store-worker scams, retailers not players are usually the ones cashing tickets.

Professional ticket cashers -- like the Massachusetts individual who redeemed 1,492 tickets valued at $2.6 million in 2007 -- are hired (often illegally) by people with something to hide, including fathers owing child support, fugitives, divorcing spouses, welfare recipients, and undocumented immigrants.

Ginther profited far more off prizes than any such scheme could yield, and the 28 prizes she claimed, ranging from $1,000 to $10 million, were from just eight high-priced instant games. A ticket casher is likely to collect prizes from all sorts of games, including daily drawings.

Morales was even more upfront. Prizes under $600 can be cashed by retailers, yet she claimed a thousand prizes of $100 or less at lottery offices, making all of them part of state records.

While Morales' cashing $88,000 in prizes over eight years is remarkable, that sum pales in comparison to what Ginther's speculated buying spree should have generated. At the prize payback rate for high-priced scratch-off games in Texas, anyone spending $1.7 million should have won more than $1 million in secondary prizes.

Reached by phone, Morales, who works in the city's water department, declined to comment.

Any illegal money-laundering scheme is even tougher to imagine, especially since Ginther was never investigated. Law enforcement tends to be on the lookout for known underworld associates winning major lottery prizes. In 2003, Jose Luis Betancourt, who won $12 million playing Lotto Texas, was convicted of various drug charges and ordered to give all his winnings back.

So many possibilities – and yet so few similarities to the Ginther case.

More on "Lottery Legend" series

Contact staff writer Peter Mucha at 215-854-4342 or pmucha@phillynews.com.