A dream had carried the boys so far from home, some 5,000 miles across the ocean to a cramped and dingy apartment in Philadelphia: a hope that ice hockey could change their lives.

Ivan Pravilov could fulfill that dream, they were told. He could take them from the daily grind of post-communist Ukraine to the gleaming ice of the NHL.

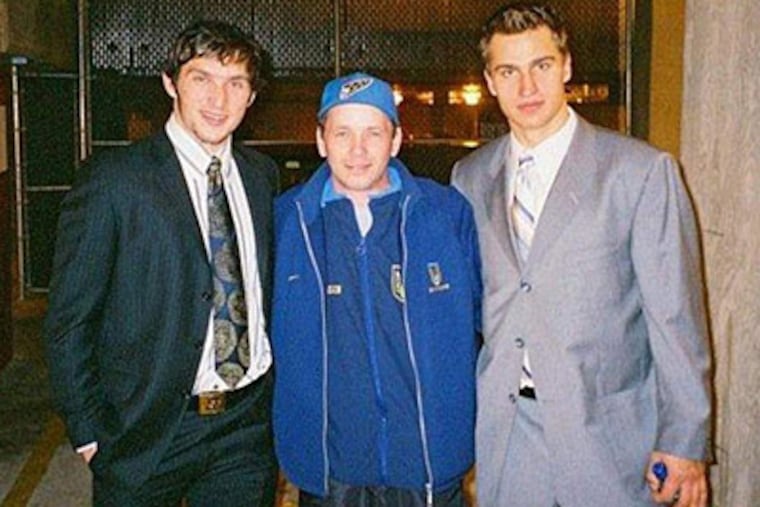

He'd done it before. He'd done if for Andrei Zyuzin, who went on to play for six NHL teams. He'd done it for Konstantin Kalmikov, a third-round draft pick of the Toronto Maple Leafs in 1996. And he'd done it for Dainius Zubrus, Pravilov's star pupil, a forward with the New Jersey Devils who had been the Flyers' first-round draft pick in '96.

Who could argue with that success? For two decades, Pravilov, 48, had produced players who trained harder, skated stronger and dominated their opponents with a machine-like efficiency that was well-known in hockey circles around the world.

In the early morning hours of Jan. 3, however, one young player would learn the price of that dream. He awoke to see a familiar, frightening form in the darkness of the small apartment in Mount Airy: Ivan. Ivan — that's what they all called him — was their mentor and their master. But now Ivan was there in the room, looming over another boy on a nearby mattress. Now he was something else — a monster.

According to a criminal complaint later filed in U.S. District Court, the boy, 14, saw Ivan kneeling and "displaying his genitals" in front of his teammate, also 14. The witness told authorities that he rustled in the bed so Ivan would realize he was awake. So he would know he was watching.

Ivan hit the boy on the head and told him to go back to sleep. Then Ivan snaked his hand under his victim's blanket toward his genitals. The witness tried to distract him again. This time, Ivan reached over and pulled the bedcover over his head.

This was the nightmare that no one ever told the boys about, the profound sacrifices they and teammates past and present had made for a future in professional hockey. Playing for Ivan meant many things: a chance to see the world, an opportunity to escape a bleak future in the Ukraine. But it could also mean a random punch in the eye in a locker room after a bad game, a hand shoving a tear-filled face into an unflushed toilet for some imagined act of defiance. And in that Philadelphia apartment on Musgrave Street, it meant something even worse.

*****

When he was young, Dainius Zubrus was the star of Druzhba-78, the youth hockey team that Pravilov had built from scratch, mostly from a group of standout soccer players in his hometown of Kharkiv, Ukraine. Zubrus wasn't from the Ukraine; he'd come from his native Lithuania to play for Pravilov in the late 1980s, not long before the team embarked on a worldwide tour to showcase its skills.

On that tour, Druzhba-78 (the name came from the fact that the team was composed of players born in 1978), would become one of the world's most-renowned youth ice-hockey clubs ... and a feel-good story: poor little boys in hand-me-down skates rising above bleak realities at home to rack up trophies and accolades wherever they played.

Because of the team's precision stick-handling and super-human stamina, Druzhba-78 was frequently compared by North American journalists to the famed Soviet Red Army teams that played a series of memorable games against NHL squads in the 1970s and '80s. Pravilov was lauded for his scientific breakdown of the art of skating, the work ethic he instilled in his young charges, for the discipline he demanded. "The Ukrainians bring an intensity, a somberness, to their sport that U.S. kids do not have, perhaps because Pravilov rules their world," the Boston Globe wrote of the team in 2005.

Agent Brian Feldman first saw Druzhba-78 in 1993 when he was 21 and working at an ice rink in Maryland. He eventually became close to several of the players on the team. Comparing Pravilov's methods to those used by the Soviets was just an easy cliché, Feldman says. Not because the Red Army teams were essentially professionals and Druzhba was made up of kids, but because Pravilov's team was actually better coached, he says; Pravilov broke new ground by deconstructing the smallest mechanics of the game. "He really could have been something legendary," Feldman says.

At practice, the boys skated forward and backward in endless loops and circles, shaving down the ice in shabby skates, until it was as natural as breathing. In the Ukraine, they'd often have to practice wearing in-line skates when power outages melted the ice in their arena. They had no need to resort to the violent, dump-and-chase style of play that defined hockey in North America. They often won games by double digits; teams sometimes couldn't clear the puck out of their zone, while Druzhba hammered their goalie with 50 or more shots. Feldman, now 40, says that the original Druzhba-78 squad is still the most unique hockey team he's ever seen on the ice at any level. "They were mesmerizing," he says. "It was like a fairy tale." On their initial tour of western Canada in 1993, Druzhba played 27 games in 44 days — and lost just once.

Yet even then there were signs that all wasn't right with the team. Druzhba-78 may have won games, but won them with little celebration; the boys on the bench silent, their heads trained to the ice. "Druzhba-78 is an aberration on skates," the Minneapolis Star-Tribune wrote at the time. "During games, they don't act like teenagers and they certainly don't play like teenagers." Another article from the same era mentioned a player staring at a can of soda that a stranger had given him, afraid to pop it open unless Ivan permitted — like a well-trained dog. Some who came in contact with the team noticed that Druzhba-78 players would at times transform from typical, happy teenagers into, as one host parent put it, "unemotional robots." It happened whenever game day approached. Or whenever Ivan came around.

Walter Babiy, a hockey enthusiast from Alberta, and Yuriy Grot, a Ukrainian journalist, were some of the first outsiders allowed to get a closer look at Pravilov's operation. In the 1990s, Babiy had helped bring Druzhba-78 to the Alberta area. On and off for several years, he and Grot traveled with the team as it toured North America. Druzhba-78 was a rare talent for sure, Babiy recalled, outscoring opponents 228 to 33 during one leg of the tour he was on. Yet he knew something was inherently wrong with the team: the marks and bruises that were out of place, the attitude that was odd for a bunch of kids playing sports. "They would hardly speak at all, about anything," Babiy says. "They had hollow eyes."

Babiy particularly noticed the bruises, the out-of-place black eyes that mysteriously emerged after the locker-room door opened. While traveling with the team, he had had to bail Pravilov out of some boorish, beer-fueled benders. And although he never saw Pravilov strike a boy, he took some of the players to see Dr. Randy Gregg, a former defenseman for the Edmonton Oilers, to look at some suspicious injuries. "He said to me, 'There's something going on here. These aren't hockey injuries,' " Babiy recalled.

Former players now say there was a reason that Druzhba players didn't "act like teenagers." In the book Behind the Iron Curtain: Tears in the Perfect Hockey Gulag that came out in December, former Druzhba player Maxim Starchenko explains in gruesome detail what it was like to play for Pravilov; where those mysterious injuries came from. If the team experienced one of its rare losses, for example — whether to boys much older or against a goon squad that physically pounded the Druzhba team — Pravilov would close the locker-room door and announce: "So my friends, get to work," a command that meant two players would have to fight, to pummel one another for the right to take a shower, or to go to the bathroom, or for no reason at all. Whoever lost the fight might later be beaten by Ivan himself. Sometimes the winner would be beaten.

According to Starchenko, more abuse took place in hotel rooms, and even at his own home back in the Ukraine, while his parents were in another room. On one occasion, Starchenko says he was forced to lick a dirty toilet while Ivan punched him in the head. "In the most literal term, he was a psychopath," Starchenko says of Pravilov.

No one was spared from Ivan's rage, says Starchenko, not even Zubrus, the team's star player. "[Pravilov] abused him in front of my own eyes," Starchenko told SportsWeek. "He could not look me in the face and say it never happened." Zubrus has publicly denied any knowledge of abuse by Pravilov, and several other Druzhba players and former coaches did not respond to requests for comment or couldn't be reached to confirm Starchenko's recollection. One Druzhba-78 teammate of Starchenko, though, Andrei Lupandin, told the Edmonton Journal that Pravilov started abusing him when he was just 9. "He took our childhood away," Lupandin told the newspaper. Starchenko's book is a brutal and frustrating read, not unlike the infamous affidavit filed against Jerry Sandusky in the Penn State sex scandal. The abuse doled out by Pravilov was mental, often physical and, at least for some, sexual, Starchenko claims. He recalls the time Ivan tried to kiss him, his breath a fetid swamp of Marlboros and alcohol. Then there was the time Ivan was laughing after sodomizing a boy with the end of a hockey stick. Starchenko writes that the players would prefer to fight one another in the locker room rather than one of the alternatives Pravilov offered: masturbating in front of the whole team. "Some looked dead, with no expression at all," Starchenko wrote about the players' reactions after one such incident.

For Starchenko, the worst incident was back in Ukraine, one night in 1990, years before Druzhba-78 would make a splash in North America. Inside a dark gymnasium on the western border of Ukraine, where Druzhba was training at the time, Starchenko and two young teammates were trying to fall asleep on the gymnasium's second-floor balcony, hoping Ivan wouldn't come for them. Fear steadily frying their nerves, they waited as the minutes stretched on, listening for the slightest sound, any hint that Ivan was on his way. For a while, the only sounds they could hear were the birds fluttering along the window sills.

But then, suddenly, Ivan was upon them, tearing off their blankets and yanking Starchenko by the collar to face him. The boy could feel his coach's breath as he shouted curses at him. A bouquet of rage bloomed across his face, turning it shades of scarlet and purple. Ivan told Starchenko it was his "judgment night." "Haven't you realized already that karma is inevitable, and I am here to fulfill that obligation as an executioner?" Ivan said to him. Starchenko thought Ivan might actually kill him right there.

He told Starchenko to take four or five steps back toward the edge of the balcony. Then Pravilov, a former professional soccer player, proceeded to kick him in the gut. Over and over, so many times that Starchenko lost track of how many kicks he endured. The other boys watched silently. The only thing Starchenko remembered was how "the noise from the kicks would always make a resounding thump throughout the gym," he recalled, and how after each, "I noticed the birds would fly away from the window."

*****

Cultural differences — the strict, regimented life in Ukraine vs. the freedoms of United States — were a major reason that Pravilov didn't draw more scrutiny once he started visiting North America, say Starchenko and others. He took advantage of a Soviet-style system that not only manufactured perfect athletes, but groomed children with little input from their parents. It was common for parents in Ukraine to never see a child play — in a practice or a game, Starchenko says. Pravilov exploited the situation. Like a cult leader, he says, Pravilov isolated boys from their families, broke them down with mind games and kept them under a constant threat of random violence.

Most of the Druzhba boys had never been out of their hometowns in Ukraine, let alone to another country where no one spoke their language. On the team's international hockey tours, which sometimes lasted more than half a year, Pravilov was responsible for every facet of the players' lives. He controlled their money, their visas, where they lived and when they bathed.

He had built the perfect system to be a predator.

What he didn't account for were the strangers, though; those American and Canadian hockey moms driving from rink to rink in their minivans, families who had invested so much time and money in their kids' passion, parents who expected to be intimately involved in their kids' lives. Ivan allowed those strangers to form tight bonds with players from Druzhba-78, and some succeeded in slowly peeling away the layers that hid the kids' pain.

Instead of constantly housing the boys in hotels, where he controlled their every move, Ivan often chose to use host families on his teams' trips to North America, where there were always people willing to open their doors to house and feed players for days or weeks. For Pravilov, the setup saved money, but there were other perks, as well. Women in those host households would often cook for him, write letters, and do other random errands, usually because their own children skated better after a few lessons from Ivan, and because they had truly come to love the boys.

But host families could also be a problem, and they caused Ivan headaches from the very beginning. In the early 1990s, Druzhba-78 won a prestigious peewee tournament in Quebec, the largest in the world. Soon after, reporters began investigating a pair of allegations regarding Pravilov: that he was milking his hosts' sympathy for money and, more seriously, that he was inappropriately touching the young teens on his team.

Pravilov denied it all. "I have been coaching these children since they were 8 years old," he told the Hamilton Spectator. "I taught them how to tie their skates. I wipe their nose for them. And, sure, sometimes I have to be severe. But to have done the things I'm being accused of ... never."

A complaint was lodged with the Royal Canadian Mounted Police against Pravilov, but no charges were ever filed, and Canadian reporters who investigated the matter later issued Pravilov a formal apology. The tournament director in Quebec, meanwhile, said Druzhba-78 was the best team to ever compete in his event. He also said he didn't want them back again because of all the turmoil.

After that, no matter where he went, Ivan usually had at least one family question his tactics. Host families in North America were accustomed to being intensely — sometimes too intensely — involved in the sporting lives of their children. And so they noticed the bruises, the fat lips and shiners that shouldn't be there when the boys were wearing helmets with full facemasks.

Wayne Kelly, who lives outside Edmonton with his wife, Judy, hosted Zubrus and another player, Gennady Razin, on a Druzhba-78 tour of western Canada. Kelly says he remembers being puzzled when Zubrus once emerged from a locker room after a loss with a bruise on his cheek. "He said he got into a fight, but I had taken a picture of him when he came off the ice, and lo and behold there was no bruise," he said. "I knew then that something was wrong."

Kelly recalled a morning in 1993 when his wife found Zubrus alone in a bedroom in their house on game day, weeping. "She asked him what was wrong and he said 'Nothing, I'm fine'," Kelly said. "She knew, though, that he was scared." When Zubrus' agent, Jerrold Colton, was asked to respond to specific claims that Zubrus was physically abused, he was adamant that nothing happened. "It's just not true," Colton said.

Razin eventually ran away from the team, calling the Kellys from a hostel in Montreal after he fled. Players like Starchenko often begged their parents to let them quit or called local families to come rescue them, only to be ridiculed and eventually prodded back to the ice. Feldman, who was close with Zubrus, Razin, and Starchenko, recalled instances when players would ask him to help them "escape" the team. "I said, 'Don't you mean leave the team,' like the English was bad or something," Feldman said. "They'd say 'no, I mean escape.' "

*****

In the summer of 2000, Elise MacKenzie says she got a call from Zubrus at her home in Minnesota. Zubrus was preparing for his first season with the Washington Capitals, but he apparently found the time to call and question MacKenzie about a story that was soon to appear in the Star Tribune.

Over the years, MacKenzie had gotten to know several Druzhba-78 players when they stayed with her while training in hockey-mad Minnesota. She had even traveled to Ukraine herself to visit the players' families. In the Star-Tribune article, she alleged that the 13-year-old boy who had been staying with her told her that Ivan was hitting the boys. "He didn't cry, but he was so afraid that I did believe him," she told SportsWeek.

When the article appeared, Pravilov's supporters accused MacKenzie of creating a smokescreen so that the boy could stay in the United States. "I know kids who would run through a brick wall for this man," an American parent named David Webb, now deceased, told theStar-Tribune.

Police in Minnesota looked into the accusations, but — as in Quebec — no charges were filed. "The whole thing was just such a big, complicated mess," MacKenzie said.

For any charge of physical or sexual abuse to stick, one of Pravilov's players would have to come forward, give a statement against the coach and possibly testify against him in court. Pravilov seemed confident that would never happen, and he would usually move on to another part of the country — or the continent — before too many people became suspicious.

Not long after the incident in Minnesota, Babiy and Grot published a book about Pravilov: Reign of Fear, alleging that all of his success, all the praise lavished on Druzhba-78, was off the mark. The reason Druzhba-78 was so good, the authors contended, was simply because the players were terrified of being anything less. "It was absolute fear," Babiy told SportsWeek. "He had control over their minds and bodies at all times."

Published in 2002, the book does not mention sexual abuse. Babiy said he wasn't comfortable addressing an issue that had been only been rumored to that point.

Despite the allegations it contained, Reign of Fear didn't do much to derail Pravilov's career. "In one word, I'd say the reaction was mixed," says Sam Budman, of Accent Ltd Publishing, which published the book. "Some people were saying, 'Why did you do that? He's one of us. And others said, 'Good for you.' " Physical punishment on and off the ice was more or less accepted by the parents in Ukraine, Budman says. "That's all right,' they'd say, 'That happens, as long he gets them in the NHL and gets them out of Ukraine.' Their kids were their meal ticket."

For the next decade, despite the coverage in the Star-Tribune and Reign of Fear, newspaper articles continued to laud the skills and exploits of Druzhba-78. By the mid-2000s, Pravilov would be bringing in multiple teams under the Druzhba banner to tour the United States for weeks at a time, mostly up and down the Northeast. By then, he was also running "Ivan Pravilov's Unique Hockey School," at arenas around the country, for which he charged $350 per kid.

Many people who came in contact with Pravilov, even many who hosted Druzhba players, say they saw nothing amiss. One, a local ice-hockey rink manager in the Delaware Valley who hosted some of the Ukrainian players, would only speak on the condition of anonymity when reached by SportsWeek. The man said that Pravilov had passed all background checks, that no one suspected him of any kind of abuse. In fact, many local parents marveled at the way he transformed the American players on the ice. "When he came to your rink for a camp, your kids were better in one week," the parent says. "It was good for the American kids to see that work ethic. He wasn't a normal guy. Very stoic, very communist, but we never had any problems with him."

Yet the problems were there — and not especially hard to discover. In 2007, for instance, Interpol, the international police organization, issued a red notice — the closest thing it has to a universal arrest warrant — after Pravilov was accused of assaulting a man at the Druzhba home rink in Ukraine. The warrant can easily be found with a basic Internet search.

According to several accounts, Pravilov had a ready story for anyone who asked about the warrant. He said the ordeal was an example of greedy officials trying to destroy his team, and used it to solicit donations.

*****

The story of Pravilov's downfall can't be told without a German ballerina turned hockey mom named Beate Proller, who first let the coach and some of his players into her Annapolis, Md., home in 2007. Ivan trusted Proller just a little bit more than the American host families he met on his trips, she told SportsWeek, maybe because she was European. Whatever the reason, it would turn out to be his biggest mistake of all.

Proller, 46, first befriended Pravilov around 2006, when she met him at the IceWorks Skating Complex in Aston, Pa., where her son often played hockey. The following year, Pravilov phoned her and said that he would be coming to the Washington, D.C., area with some players and needed a place to stay. She agreed to host, and Ivan and a young Ukrainian boy lived with her and her sons for the duration of their stay.

Over the next several years, Pravilov would often stay with Proller when he had a team touring the area, and the family soon developed a deep relationship with one of the players.

In 2009, though, Proller began to notice that the boy would try to avoid Ivan if he could. "He never wanted to be alone in his own room," she says. "He always insisted on sleeping on the floor in my son's room. There was a huge difference in the way he tensed up when Ivan was around and how he relaxed when he was gone."

Eventually, Proller confronted the boy. "He looked at me and said, 'I can't tell you. I cannot ever speak this to anyone, not even my mother,' " Proller recalled the boy saying to her.

Proller began to search the Internet, shocked at the history of allegations she found against Pravilov, a trail that stretched from the Ukraine to Canada to the United States. Then, one day in March 2009, during a stretch when Pravilov and the boy were staying with her, she came home early from work to discover a disturbing scene. As she entered, she says, the boy ran upstairs, naked. "Ivan was undressed as well, scrambling to put his clothes on."

Pravilov seemed panicked, Proller said, and she feared that he would flee for good if she confronted him there. She later spoke to police, but they told her that without a witness, there would be no case, she says. She knew that the boy wouldn't talk, at least not yet, so she worked even harder to develop his trust. "He was scared of what the other boys would think, but I told him that one day you'll have had enough," she said.

Over next two years, Proller says, she made inquiries with local and federal law-enforcement agencies, hospitals, and social-service agencies, reiterating every time that she believed Pravilov was abusing his players. Often, she says, officials would approach the players only to be rebuffed. No player was willing to come forward. The other complicating factor, says Proller, was the fact that none of the boys was American. The boys' parents were thousands of miles away from home and it wasn't always clear what officials could do even if they believed something had happened.

Proller, it should be noted, has her detractors. There are more than a few hockey parents who called her "nuts" and rink managers who balk at her contention that she was ringing the alarms about Pravilov's physical abuse while others did nothing about it. Law-enforcement officials have refused to wade into the name-calling, but they admit Proller was zealous in her determination that Pravilov was an abuser who had to be stopped. "I will tell you this, I wouldn't want her after me," says Sgt. John Kelly, with the Delaware County District Attorney's Office Child Abuse Unit. "She went up against some walls and people didn't believe her, but she kept on going at it."

Proller remains unapologetic about her efforts. "So many people knew about it and covered it up and I feel like these people are guilty. They failed to do the right thing for these children," she says. "This has been going on for 25 years. It's been way too long and he hurt too many people."

Finally, in late 2010, out of frustration, Proller called the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children to state her concerns. The center referred the matter to the Delaware County District Attorney's Office, which is how Kelly got on the case. "This thing had gotten lost in the cracks," he says.

In the summer of 2011, Kelly began to investigate Pravilov. One day, he visited IceWorks in plainclothes just to check out Pravilov and the kids. Although he admittedly knows little about ice hockey, the talent of Pravilov's teams was obvious, even if the silence was odd for a group of teens. "They just killed the American teams," he says. "There was no comparison whatsoever. But those kids sat on that bench every time I was there and never said a word, ever, to one another."

Because of the various international issues involved with the allegations, Kelly contacted the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement's Homeland Security Investigations division to take over the case. Despite the added firepower, however, it was clear that the case would still need a break if Pravilov were ever to see the inside of a courtroom. That break finally came in January, after a 14-year-old Druzhba player witnessed Pravilov molesting a teammate in the Mount Airy apartment where the coach had brought the boys.

To Pravilov's chagrin, the boy who witnessed his friend being molested was a rarity in his world: a rebel. The boy didn't force himself back to sleep that night, guilt-ridden yet relieved that Ivan had chosen someone else. He didn't keep quiet about it, either. He went online and messaged his friends about what he had seen.

Through his assistant coaches, Pravilov learned that the player was talking. Ivan usually dealt with defiance immediately, and 10 days after the incident, he confronted the boy in a locker room at The Rink at Old York Road in Elkins Park.

"Should I kill you?" Ivan supposedly asked the boy. Then he struck the boy on the neck.

But the boy was not going to be intimidated. Almost immediately after the locker-room confrontation, the Wilmington family hosting him contacted authorities. Investigators could still see the mark on the boy's neck when they interviewed him.

It turned out that this moment had been coming for years: the boy Pravilov confronted — the boy who had seen his teammate molested in that dingy apartment — was the same boy that Beate Proller had encouraged to come forward years earlier.

On Jan. 26, Pravilov was arrested and charged with sexual abuse.

*****

During an initial court appearance in Philadelphia after his arrest, Pravilov urged the judge to set an earlier date for his bail hearing because his team was "beheaded" without him. Behind the scenes, sources say Pravilov was increasingly worried that players and Druzhba-78 assistant coaches — many of whom were former players — were lining up against him. Proller claims Pravilov sent her a Facebook message from prison, where he threatened to have her and her son murdered. "You are a rat and you will rot in hell for betraying me and getting the kids talking to police," he allegedly wrote.

Because both Pravilov and the minors involved were in the United States on visas, thousands of miles away from their home country, the case was inordinately complicated, says John Kelleghan, special agent in charge of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement's Homeland Security Investigations in Philadelphia. By the time Pravilov was arrested, investigators were working to find more victims and had even planned to travel to Ukraine to conduct interviews.

Sources familiar with the case say Pravilov immediately sought help from Zubrus, who had known Pravilov for almost 20 years. Although Zubrus left the Flyers after the 1998-99 season, he still owns a home in Cherry Hill that Pravilov had used as a mailing address for years. Colton, Zubrus' agent, appeared on Pravilov's behalf at his initial court appearance (although Colton did not represent him at any point after that).

Pravilov often cited Zubrus as his "protégé" and played up his connection to the NHL stalwart on his now-defunct website and in fliers for the skating camps he hosted in the United States. After the arrest, reporters reached out to Zubrus for a comment. "I still keep in touch with him," he told the Newark Star-Ledger in January. "It's disappointing. Obviously I never thought in my head he'd ever be accused of something like that. But there is a lot of stuff going on back in the Ukraine. He has a lot of enemies there. I'm sure the truth will come out."

A source said that Zubrus visited Pravilov in jail in early February. Although he hadn't publicly condemned Pravilov, or admitted that he was a victim of abuse himself (as others have claimed), the source says the married of father of two was finished with Ivan, and his only concern was for the players.

The morning after Pravilov met with his most-prized player, he was found dead in his cell. He had hanged himself.

Zubrus declined to comment for this story, but he did issue a brief statement after the suicide: "Unfortunately, I have come to learn that in actuality, he may have been very different than the person I thought he was," the statement said. "Since learning of the terrible accusations against my former coach, all my thoughts and concerns have been for the children. I have reached out to the children, and assured them that I am, and will continue to be, there for them."

Among those children were the only real heroes in this tragedy, the two 14-year-old boys who finally spoke out against their coach after so many others could not. They had much to lose by outing Pravilov, and both are back in Ukraine now, free from their coach but so much farther away from any future in professional hockey. "All they wanted to do was play hockey. That was going to be their life," says Kelleghan. "It's all been put in limbo."

Pravilov's death brought the case to a close, so it's impossible to say how many victims the coach may have had, how many people in the world are still struggling to come to terms with what he may have done to them. But his suicide also ended the possibility that his young players, children who just wanted to play hockey, would have to testify against him, would have to confront him face-to-face. It was, perhaps, the only time he ever spared them from pain, says Kelly. "I think it's the best thing that ever happened to the kids."

To return to The Best of SportsWeek, click here.