Ligambi defense seeks tape of Merlino

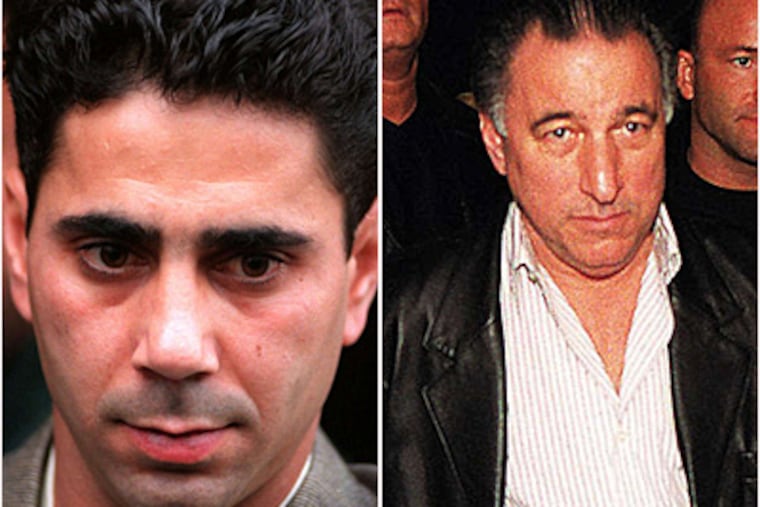

Florida-based Philadelphia mob boss Joseph "Skinny Joey" Merlino had at least one meeting with mob informant Nicholas "Nicky Skins" Stefanelli while Stefanelli was wearing a body wire for the FBI, federal authorities confirmed last week.

Florida-based Philadelphia mob boss Joseph "Skinny Joey" Merlino had at least one meeting with mob informant Nicholas "Nicky Skins" Stefanelli while Stefanelli was wearing a body wire for the FBI, federal authorities confirmed last week.

But prosecutors say the conversation, recorded in Florida sometime in 2011, has nothing to do with the mob racketeering case pending in U.S. District Court against several top Merlino associates, including alleged "acting Philadelphia mob boss" Joseph "Uncle Joe" Ligambi.

Ligambi's defense attorney, Edwin Jacobs Jr., has said he would like to make that determination himself. He has asked U.S. District Court Judge Eduardo Robreno to order the prosecution to turn the tape over to the defense before the start of the trial.

Jury selection begins Oct. 9. The trial, a racketeering case built around allegations of gambling, extortion, and loan-sharking, is expected to last eight to 12 weeks.

Though Merlino, 50, is not a defendant, he has emerged as a presence in the courtroom during several pretrial hearings. So has Stefanelli, a Gambino crime family soldier who recorded dozens of conversations for the FBI before committing suicide in March.

Two tapes Stefanelli made at meetings in North Jersey restaurants will be played for the jury during the trial.

At one lengthy lunch meeting at the posh La Griglia restaurant in Kenilworth, three codefendants and five members of the Gambino crime family, including Stefanelli, talked for hours.

Prosecutors hope to play about 90 minutes of conversation from that session, which Assistant U.S. Attorney Frank Labor has compared to a "meeting of the board of directors of organized crime."

The conversations, according to transcripts that have been made public, included several references to Merlino, who was finishing a 14-year prison sentence on racketeering charges at the time.

"I think fair play should entitle us to hear the Florida tape," Jacobs, Ligambi's lawyer, said after last week's hearing. "We obviously can't cross-examine Stefanelli. I think we're entitled to know whether he said something in Florida that might conflict with what he said during the restaurant meetings."

Judge Robreno has asked for more details from Labor.

The prosecutor said during the Sept. 24 hearing that he had not heard the tape but had read a "summary" of its contents. Labor said he believed the conversation had no relevance to the pending case and that the defense was not entitled to it.

He said the tape was in another jurisdiction and not under the control of his office or the local FBI. He also argued that there might be "security" issues in disclosing the tape.

Stefanelli, 69, was a major operative for the leaders of the Gambino crime family when he began cooperating, and he apparently met with mobsters up and down the East Coast. He was working primarily for the FBI and federal prosecutors based in Newark, N.J., and New York.

In addition to the Ligambi trial, a mob boss in Rhode Island is under indictment in a case that includes taped conversations with Stefanelli.

The implication in the legal debate over the Florida tape is that Merlino could be the focus of an ongoing investigation in another jurisdiction: South Florida, Newark, or New York.

The fact that Stefanelli traveled to Florida and met with Merlino while wearing a body wire would indicate the meeting was part of an FBI probe.

No other details about what was said at that meeting have been made public.

Merlino moved to Florida after finishing his prison sentence. He spent about six months in a halfway house in West Palm Beach before moving to the Boca Raton area.

According to several sources, the former Passyunk Avenue celebrity gangster is living in a four-bedroom, three-bath condo about a mile from the beach. He drives a Cadillac Escalade and frequents several local bars and restaurants that cater to a young, hip crowd.

An FBI "situational information report" filed shortly after he moved to Florida suggested that Merlino "appears to be . . . developing relationships for a potential South Florida crew" and "may become involved in illicit gambling/bookmaking activities again."

Merlino, who seemed to enjoy the media spotlight in Philadelphia, has turned down requests for interviews since his release. Sources who have spoken with him said he intends to stay in Florida and wants to put his criminal life behind him.

He has spent about 16 years of his adult life in prison, with convictions for racketeering and for an infamous armored-car heist in which $357,000 in cash was stolen. Merlino was convicted of masterminding that robbery and was sentenced to four years in prison. The money has never been recovered.

In moving to Florida, Merlino had hoped to avoid the limelight, friends say, and to begin his life over. Among other things, he had hoped to get involved in the bar and restaurant business, they say, and had toyed with the idea of selling rights to his life story to a movie company. Neither has happened.

Law enforcement sources say they are curious about how Merlino, after spending more than a decade behind bars, was able to walk out of prison and into a lavish lifestyle with little means of support.

The FBI situational report alleged that Merlino had reestablished connections with some members of the Philadelphia mob now living in Florida and with members and associates of the New York and North Jersey Lucchese and Gambino crime families who were also in the area.

Those connections may have led to the meeting with Stefanelli, according to investigative and underworld sources. But if federal prosecutors in the pending Ligambi case have their way, what was discussed at that meeting will remain part of an investigative case file rather than the public record.