A brother's spy act helps police capture a killer

A little more than 24 hours after Shamsiddin "Snap" Sallam shot Greg Jarvis dead in West Philadelphia on Sept. 7, 2009, the killer's phone rang.

A little more than 24 hours after Shamsiddin "Snap" Sallam shot Greg Jarvis dead in West Philadelphia on Sept. 7, 2009, the killer's phone rang.

"Yo, Snap, this is Jarvis," said a familiar voice. "I'm still breathing."

Snap stuttered - "Who? Who is this?" - and hung up.

In that moment, a trap had been sprung, and Snap Sallam had no idea.

Sallam and Jarvis had kept in touch since prison, both still dealing drugs. On the morning of Sept. 7, Labor Day, Sallam told Jarvis he had new connections and would repay a debt owed from a previous deal. He just needed Jarvis to advance him more drugs.

Jarvis said he would bring a half-brick of cocaine, police said, about $17,000 worth, to a first-floor apartment near 62d and Callowhill Streets. The apartment belonged to Harry Williams, another Sallam friend from prison.

Jarvis left home around noon.

In the apartment, police said, Sallam opened fire without warning, shooting Jarvis and Williams multiple times before fleeing.

"It was an execution," said George Pirrone, the Philadelphia Police Department's lead detective in the case. "Sallam was trying to come up again in the drug world, and he knew he'd never make any money if he had to repay everything he owed."

Police don't believe Jarvis was a big-time dealer, Pirrone said. He went unarmed and alone to the meeting, a mistake no hardened criminal would make.

Police arrived at Williams' apartment shortly after 3:30 p.m., after a neighbor called 911. Williams, shot at least four times, was hospitalized in critical condition. Jarvis was dead.

'My brother got shot'

Andres Jarvis was not a cop, and he never wanted to be one. But over the next three months, he would become the best weapon a homicide detective could ask for.

Born a year and a half apart, Andres Jarvis and his brother Greg were often mistaken for twins; even their voices were similar.

Grief-stricken and angry a day after Greg's murder, Andres drove 700 miles from South Carolina to Greg's Allentown house. He needed to know what happened to his "little big brother."

Greg's fiancee said he had been going to meet a man named "Snap." Andres urged her to find the man's phone number.

Greg Jarvis' online call log showed seven calls from one number before 3:30 p.m., when Jarvis was killed, then nothing. Andres Jarvis dialed the number.

He chose his words for maximum effect. "I'm still breathing" came from a rap song Greg had recorded. Sallam's reaction confirmed his suspicion: Sallam was the killer.

Andres called Sallam back that day, and this time he identified himself.

"My brother got shot and killed in Philly when he came to see you," Andres said.

"I don't know nothing about that," Sallam replied. But he kept talking.

Hoping to sow seeds of paranoia, Andres said dealers were looking to get paid for the money Greg was supposed to collect. Andres implied that he was looking to pick up where his brother left off. But Sallam declined Andres' invitation to attend Greg's funeral.

From then on, Andres set out to earn Sallam's trust and draw out information vital to police. For the next three months, the two talked about everything from the Philly drug trade to Greg's budding music career.

After the first conversation, Andres contacted Pirrone and gave him Sallam's number. That allowed detectives to request his phone records, which would show that Sallam also called Williams five times in the hour before the murders.

Fighting the wrong fights

Developing a relationship with his brother's killer was an unexpected turn of events for Andres, 39, a soft-spoken family man with no criminal background. But his life took on the singular focus of putting Sallam behind bars.

"It was all I thought of for so long," he said in a recent interview. "Every week when I cut my grass, I would review it all in my head, go over and over it, so I wouldn't forget anything. . . . I just needed to feel I was doing something."

Despite their striking physical similarities, Andres and Greg went in different directions more than two decades ago.

After a childhood on St. Croix in the U.S. Virgin Islands, their mother moved them and their two sisters to Reading in 1985. They went from climbing trees barefoot to playing basketball on pavement.

Andres did well in their new life, but Greg struggled. He didn't know how to walk away from a fight, and was sent to an alternative school after a fight at school.

"He was a protector," Andres Jarvis said. "Loyal to a fault. He took on people's fights, whether they were right or wrong."

After graduating from high school in 1992, Andres shipped off to Virginia with the Navy. The next year, Greg went to prison for stabbing a man.

At Smithfield State Prison, Greg met Sallam, who was in for assault and gun offenses.

After Greg's release in 2000, he moved to Allentown, where he focused on a growing interest in hip-hop and reggae that had blossomed in prison. He met his future fiancee, Veronica Montes, and they had two children.

Greg's record made it difficult for him to find steady employment, and money was tight. By now, Andres knew from the wad of cash Greg carried that he was selling drugs; Greg said he just wanted to provide for his family's future.

In 2005, Greg's music began attracting local interest, and in 2008 he got a recording deal and a signing bonus that he used for a down payment on a house. His label booked a tour of venues near area colleges.

But the money ran out and Greg's mortgage went under. Andres dug into his 401(k) to keep his brother from drugs, believing that once he went on tour and finished the album, the money would come.

"People believed in his talent, so everything was looking good," Andres said. "It was just a matter of getting him to that next point."

The circle closes, a weight lifts

Andres and Sallam would discuss Greg's music as much as they did his murder, as their relationship solidified in the months after the killing.

"I just want him to be even-keel. I don't want to push him away or force him not to take my calls," Andres told a judge in a September 2010 preliminary hearing.

Often Sallam asked Andres if he had heard anything about Williams, the other victim shot.

"He'd ask, was he alive? Was he talking? Did the police say anything about him?" Andres said. "He was real concerned about him waking up and saying something."

A month after the shooting, on Oct. 3, Williams died.

Meanwhile, detectives strengthened the case against Sallam. Outdoor surveillance footage from a corner store showed Greg and Sallam entering the home shortly before the shooting, then one of them running from the building moments later.

And in the weeks after the murder, police had spoken to a man who said Sallam confessed to the killings and wanted help selling the stolen drugs.

By the end of October, police had a warrant for Sallam. They couldn't locate him, but Andres kept in contact by phone, baiting him with stories about thugs looking for Greg's stolen drugs.

Members of the fugitive squad nabbed Sallam on April 12, 2010, in North Philadelphia.

When Andres walked into court to testify a few months later, Sallam appeared shocked at seeing Greg's double. "He couldn't look at me," Andres said.

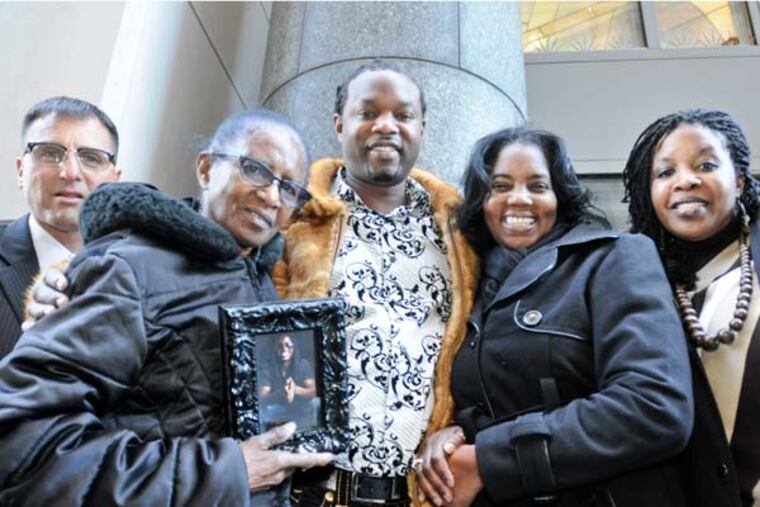

Andres recounted his detective work at the five-day trial in December 2012. Sallam was found guilty and sentenced to life in prison.

Prosecutor Richard Sax said Andres' help was critical: "Without Andres, we don't know how the case would have proceeded."

And Andres' burden was gone.

"I physically felt the weight lift. . . . I felt like, I did it," Andres said. "I know Greg's not coming back, but I got him."