Booth mystery must remain so - for now

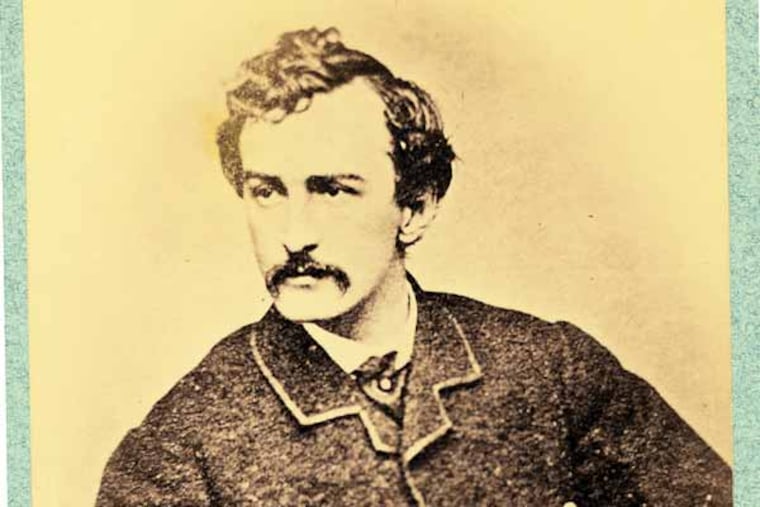

The drama is clearly the longest running of any that John Wilkes Booth played during his acting career. Was Booth, the assassin of Abraham Lincoln, killed by a soldier at a tobacco barn near Port Royal, Va., on April 26, 1865, as history books and government accounts record?

The drama is clearly the longest running of any that John Wilkes Booth played during his acting career.

Was Booth, the assassin of Abraham Lincoln, killed by a soldier at a tobacco barn near Port Royal, Va., on April 26, 1865, as history books and government accounts record?

Or was someone else shot through the neck and declared to be Booth as a way of putting an end to the national tragedy? Did the president's killer actually escape?

Though those questions are settled in the minds of most scholars, they have intrigued and frustrated some historians and Booth family members, including some locally, who hoped to finally find answers.

But this month, just two weeks before the assassination anniversary, they were disappointed when the Army thwarted an effort to compare the DNA from the man in the barn with that of Booth's more famous thespian brother, Edwin.

Their request for access to an alleged Booth specimen - three cervical vertebrae in the collection of the National Museum of Health and Medicine in Washington - was rejected.

"Although the results might be intriguing, and the temptation to exploit emerging technologies is strong, the need to preserve these bones for future generations compels us to decline the destructive test," wrote Carol Robinson, the Army's congressional actions manager for the U.S. Army Medical Command, which oversees the museum. "The three vertebrae that were removed during an 1865 autopsy, believed to be [of] John Wilkes Booth, are unique and DNA testing may or may not yield the information desired," said the letter to U.S. Rep. Chris Van Hollen (D., Md.), who helped submit the request.

The answer is "beyond disappointing. . . . I'm angry," said Joanne Hulme, a Booth family descendant who lives in Philadelphia's Kensington section. "I would like to know who's buried in the family plot" in Baltimore's Green Mount Cemetery, where the assassin is allegedly interred.

"This never ends," she said Friday. "I may take this to my grave, but I will take it kicking and screaming."

Hulme's family and others - including Maryland educator and historian Nate Orlowek - sought permission in 1995 to open the grave believed to be Booth's but were thwarted by a judge who concluded its location could not be conclusively determined. Some reports had placed it at an undisclosed site in the cemetery.

That left the cervical specimen as the next best way to determine whether Booth or someone else was killed.

Its DNA could be compared with Edwin Booth's DNA retrieved from his grave in Cambridge, Mass., the family has said.

Philadelphia's Mutter Museum has cervical tissue of the man in the barn, but its DNA has been degraded by storage in formaldehyde and alcohol.

"We, the American people, own" the National Museum of Health and Medicine, said Orlowek, who has researched questions surrounding Booth's death for 40 years. "Why on earth should we spend millions of dollars to maintain a museum that withholds the decisive piece of evidence that would solve the greatest crime in American history?

"The American people should demand that they stop holding history hostage," he said Friday. The search for the truth "is only over if the American people allow this museum to stiff-arm history."

The testing of the specimen would not have seriously damaged it, said Krista Latham, director of the University of Indianapolis Molecular Anthropology Laboratory, and an assistant professor of biology and anthropology who would have performed the DNA test.

"We would have only needed 2 grams of bone," she said Friday. "That's a small amount, and it would have been minimally destructive.

"This is frustrating. This is a very important issue, and the worst thing we could do is give up."

For those questioning accepted history, the crucial days of April 1865 play over and over.

At 9 p.m. on the 14th of that month, Booth walked into Taltavull's Star Saloon next to Ford's Theatre and asked for a bottle of whiskey and some water.

"You'll never be the actor your father was," a customer reportedly told him.

"When I leave the stage, I will be the most famous man in America," Booth fired back, according to accounts.

An hour and a half later, the dark-haired actor - matinee idol of his time - shot Lincoln in the State Box at Ford's and dropped about 11 feet to the stage, breaking his left leg.

History says Booth was cornered 12 days later by detectives and Union soldiers in the barn in Port Royal. Shortly after 2 a.m. on a cool and cloudy Wednesday, he was mortally wounded in the neck.

Or was he?

From the beginning, several people who saw the body questioned the official account. The dead man didn't resemble the fair, raven-haired Booth. He had red hair, was freckled, and had a leg injury inconsistent with the assassin's. The questions will linger "as long as the demands of the American people for the truth are ignored," Orlowek said. "They have to let their voices be heard."