In Kensington, a rent-to-own deal that wasn't so sweet

In July, a property manager for a company called Kenpor L.P. offered Ruth Roman a deal: She could rent the shell of a house at 2023 Castor Ave., fix it up and, in a few years, take ownership.

In July, a property manager for a company called Kenpor L.P. offered Ruth Roman a deal: She could rent the shell of a house at 2023 Castor Ave., fix it up and, in a few years, take ownership.

She's put more than $10,000 into new plumbing, flooring, heaters, appliances and roofing, and has begun paying $700 per month toward a purchase price of $28,400.

Now she's worried she could lose it all.

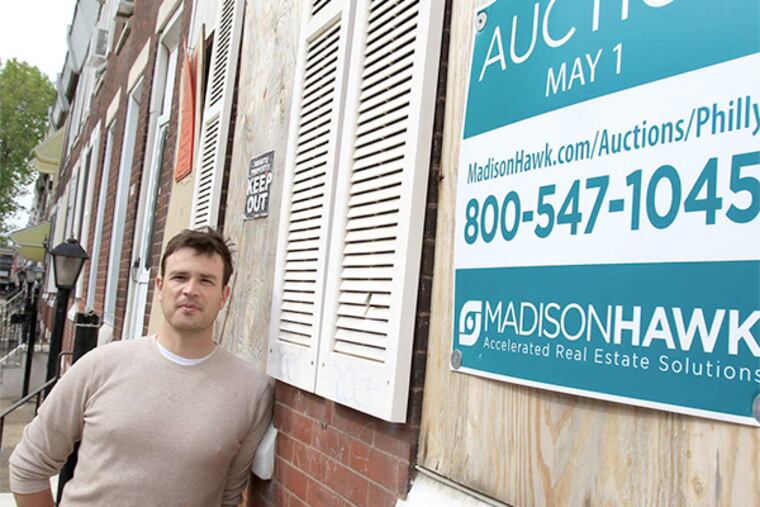

In April, Roman learned that her house will go up for auction Tuesday, along with at least 85 other properties in Kensington once owned by convicted scammer Bob Coyle.

"I don't want to be out on the street," Roman said. "This is our home. It's not done, but it's getting there. It's not perfect, but it's just right for me and my family."

To anyone who has followed Coyle's story, Roman's plight will sound familiar. Coyle put hundreds of tenants into rent-to-own agreements, then defaulted on more than $10 million in mortgages on the properties, leaving the renters in limbo.

Developers said there's a reason history is repeating: There's virtually no other profitable way to dispose of homes that could cost $40,000 or more to rehab - but, even fixed up, are not worth much more than that.

Given that troublesome math, even as prospective buyers prepare their bids, those who live and work in the area fear the cycle of blight is about to reset.

"I'm very concerned," said City Councilwoman Maria Quiñones Sánchez, who had urged Kenpor to prescreen the bidders.

"None of these houses is going to be refurbished without some level of subsidy," she said. "I don't see how any private investor can make the numbers work."

A Department of Licenses and Inspections spokesman said the department offered to review the list of registered bidders to weed out any chronic slumlords. Kenpor had not, by Monday, taken L&I up on the offer.

It's more than just the balance sheets of bidders at stake.

The fates of these properties will affect the whole neighborhood, said Jamie Moffett. The filmmaker turned activist keeps a studio at H and Westmoreland Streets, in the middle of Coyle country; 40 Kenpor parcels lie within a half-mile radius.

Moffett and others have been trying to clean up the area: tidying trash-filled lots, locking up alleyways, installing floodlights, sealing vacant houses, and posting no-loitering signs.

But Coyle's legacy, paired with other vacancies, continues to attract crime and depress property values.

"The guy's been in jail for a year, yet he still has a stranglehold on the neighborhood," Moffett said.

A 2012 analysis of shootings and vacancies by Joel Caplan, associate director of the Rutgers Center for Public Security, underscored that point.

"Gun violence is not happening randomly in the Kensington area," Caplan said. "It's in fact clustering closer to vacant properties."

Citywide, he found, the chance of a shooting decreased by 24 percent for every block moved away from a vacant property.

Given the high concentration of those properties, Moffett and others were hopeful when Kenpor cut a deal to buy the properties in 2012.

But when Kenpor circulated a price list asking more than $30,000 for many of the properties, those hopes were dashed.

Partly as a documentarian, partly as a potential investor, Moffett has photographed 30 of the houses, collecting dozens of portraits of ruin and neglect.

He's fixed up five nearby properties himself, and started an organization, Kensington Renewal, that aims to boost home ownership in the area. But he's ended up renting the rehabbed properties, unable to sell them.

Phyllis Martino of the Kensington nonprofit Impact Services Corp. said she expects, given the area's bleak real estate market, that most of the properties sold at auction will ultimately be rented.

Others, she said, should probably be demolished.

"Anything that reduces vacancies can be helpful. But do you want a lot of absentee landlords who keep the place in bad condition?" she said. "I think the saga will continue."

In 2010, Jeffrey Allegretti at Innova, a Philadelphia developer, reviewed a different portfolio of former Coyle properties for potential subsidized redevelopment. It didn't work out. "This is a really tough portfolio," he said. "Getting them for nothing might not be cheap enough."

He estimated the cost of refurbishment, per house, at $80,000. Shortcuts - say, fixing a roof rather than replacing it - would only set up low-income buyers for disaster if they cannot afford repairs.

"Without a subsidy, I couldn't figure out how to make it work," he said. "Maybe [rent-to-own] is the only way. But that's a flawed model, as the outcome proves, because the people who get involved in rent-to-own have limited income and poor credit. Those people are the least likely to be able to take on the home-repair burden."

Putting that burden on the tenant isn't legal in Pennsylvania, said Mike Carroll, supervising attorney at Community Legal Services of Philadelphia. Even if it were, rent-to-own deals often leave tenants vulnerable.

"I can't recall one where the tenant ended up with ownership," he said.

Still, for Roman, who's on disability and has bad credit, this is her shot at owning her own home.

She said it's an investment in her family.

"My daughter just turned 14, and at first she didn't want to go in there. She was scared," Roman said. In the bathroom, to keep from falling to the floor below, they had to balance on three beams. Now, Roman has repaired that, and is saving up to refurbish the kitchen.

"The first thing I did was her bedroom," she said. "Because I wanted her to be comfortable."

215-854-5053

@samanthamelamed