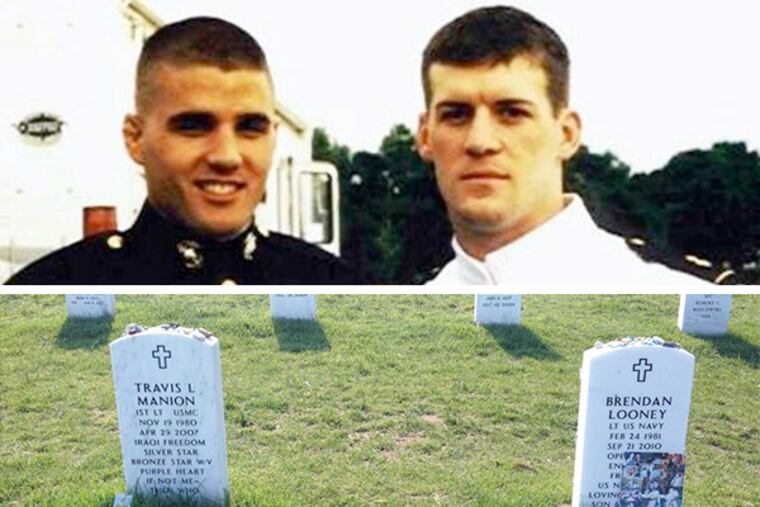

The Pulse: Side by side, an eternal bond

As Thanksgiving approached in the fall of 1999, 18-year-old Naval Academy plebe Travis Manion was convinced he'd made a mistake. Missing the freedoms associated with conventional college life, he decided that he was not suited for the academy. All that stood between him and the exit door was a battalion officer, Lt. Col. Corky Gardner, who just happened to be a friend of Travis' father, Tom, himself a 20-year Marine.

As Thanksgiving approached in the fall of 1999, 18-year-old Naval Academy plebe Travis Manion was convinced he'd made a mistake. Missing the freedoms associated with conventional college life, he decided that he was not suited for the academy. All that stood between him and the exit door was a battalion officer, Lt. Col. Corky Gardner, who just happened to be a friend of Travis' father, Tom, himself a 20-year Marine.

Gardner implored Travis to first speak to his parents. A restless holiday weekend ensued at the Manion residence in Doylestown, where Col. Tom Manion told his son that although it was his decision, he was "making a big mistake." Travis decided to leave. But after only one semester at Drexel University, he realized his father knew best. Reapplying to the Naval Academy was at least as difficult as initially gaining admittance. And only when Gardner personally extended himself with a written recommendation was Travis Manion welcomed back, now as a member of the Class of 2004.

It was in Annapolis that Manion watched the events of Sept. 11 unfold, while gathered around a television amid other midshipmen, including Brendan Looney. Manion, a wrestler, and Looney, a football player who turned to lacrosse, were in the midst of forming a strong bond. Watching news of the attack confirmed the desire that each had to serve his country, including a willingness to stand in harm's way. So struck by the events of 9/11 was Manion that he visited New York Fire Department's Rescue 1 unit and came home with mementos. To his father he gave a baseball hat with the Rescue 1 FDNY logo on the front and "9-11-01 Never Forget" on the back. He told his father, "Always remember this is what we're fighting for."

Three years after terror struck America, Manion and Looney graduated as officers in the Marines Corps and Navy, respectively. Looney eventually became the first to receive a waiver for color blindness into the SEAL program. Manion was the first to deploy, to Iraq, and after his first tour of combat, returned to his family in Bucks County.

While resting up before a second deployment, on Dec. 4, 2006, he accompanied brother-in-law Dave Borek to an Eagles game at Lincoln Financial Field. Soon he'd be reengaged in the bloody battles of Iraq, but for one night he sought solace watching his beloved Eagles beat the Panthers, 27-24. Exiting the Linc, Borek joked to Manion that if he tripped him and caused an ankle break, Manion could sit out the deployment.

"You know what, though, Dave?" Manion replied. "If I don't go, they're going to send another Marine in my place who doesn't have my training. If not me, then who? . . . You know what I mean?"

Four months later, on April 29, 2007, Tom and Janet Manion awoke to a glorious sunny day. They spent part of Sunday morning watching Tim Russert question Sen. Joe Biden on Meet the Press. The Manions winced when Russert asked Biden whether the war in Iraq "was lost."

On the other side of the globe, in Fallujah, a team of Marines was on a mission in the "Pizza Slice," a distinctively shaped section of narrow alleys between two arteries, in search of a sniper. Worn down from battle, First Lt. Chris Kim had asked Manion to take his place. He readily agreed. On the mission, Manion was felled by a sniper.

Stateside, a general who knew Tom Manion got word of the death. He immediately placed a call to Corky Gardner - the same man to whom Travis had tendered his Naval Academy commission and who had supported his reapplication. Gardner, though now retired, had stayed in touch with Travis during his deployment. Leaving church in Ardmore with his wife, Gardner retrieved a voice mail, learned of Travis' death, and immediately agreed to accompany a young Marine, First Lt. Eric Cahill, who had the unenviable task of going to the Manion residence to break the news.

For the 96th time in the first 29 days of April 2007, the military was about to inform a family that a son or daughter had made the ultimate sacrifice in Iraq. It took a moment for the Manions to realize why Gardner stood outside their door. When reality struck, Janet Manion was so overcome she slammed the door with a force that tore its hinges. Tom, after being told of the death of his only son, maintained the presence of mind to offer: "Lt. Cahill, you did a fine job."

Three thousand miles away in San Diego, preparing for the SEALs' arduous underwater demolition training, Brendan Looney got the news. Upon completion of that training, he gifted the gold trident pin that every Navy SEAL earns to Janet Manion. By now, Travis had been buried at Calvary Cemetery in West Conshohocken.

Looney was initially deployed to Fallujah, where he saw those hot spots where Travis had served and died. Looney's second deployment was to Afghanistan. On Sept. 21, 2010, in the midst of his 59th mission, he perished in a helicopter accident that killed nine in Zabul province.

Back home in Doylestown, the Manions felt as if they had lost a second son. Along with the Looneys, they decided the former roommates should spend eternity together. Today, the graves of Travis Manion and Brendan Looney rest side by side in Section 60 of Arlington National Cemetery. And now, Tom Manion, assisted by Tom Sileo, has written an emotional tribute to both men titled Brothers Forever.

"Throughout our history, generations have continued to answer the call to defend our nation, and none more proudly than today's volunteers. This book is for them," Tom Manion writes in the book's acknowledgments.

"Some of these guys have been over there for 10 years; some have served two or three terms," he told me last week. "We are trying to connect them and the country with their service. These kids are like the kids up the block."

That the story of two members of this new great generation deserves to be told was evidenced by President Obama's remarks at Arlington three years ago this weekend:

"Heartbroken, yet filled with pride, the Manions and the Looneys knew only [one] way to honor their sons' friendship - they moved Travis from his cemetery in Pennsylvania and buried them side by side here at Arlington. 'Warriors for freedom,' reads the epitaph written by Travis' father, 'brothers forever.' "