Free black woman's voice is still clear, 150 years after Civil War era

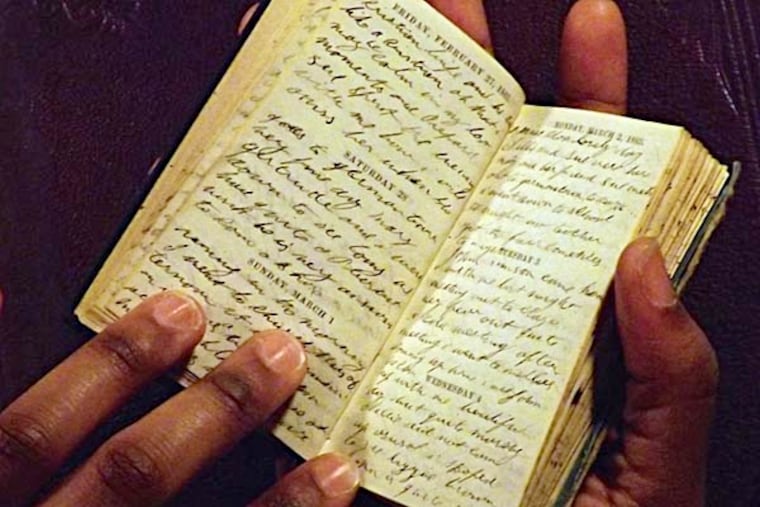

The worn, leather-bound diaries, each about the size of a smartphone, reveal a voice rarely found in print. In them, Emilie Davis, a young housekeeper and seamstress, chronicles her life as a free black woman in Philadelphia during the Civil War.

The worn, leather-bound diaries, each about the size of a smartphone, reveal a voice rarely found in print.

In them, Emilie Davis, a young housekeeper and seamstress, chronicles her life as a free black woman in Philadelphia during the Civil War.

"To day has bin a memorable day and i thank god i have bin sperd to see it," Davis wrote in an entry dated Jan. 1, 1863, the day the Emancipation Proclamation became official.

It is the first sentence in a series that fills three pocket diaries, recounting Davis' life from 1863 to 1865. An unparalleled find, it has been stored in the archives of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, which acquired the diaries 15 years ago.

Since then, what had been a hidden treasure is becoming more widely known.

Davis' diaries have been digitized by one university, and transcribed online and annotated by another. They are the subject of a short play, a prospective novel, a forthcoming documentary, and two books, with a third due to be published in two weeks.

"The diaries are exquisite," said Judith Giesberg, an associate professor at Villanova University who specializes in the Civil War. "We have very few first-person accounts from women of color."

The diary's significance is magnified because the free black community during the Civil War stands in "evidentiary silence," Giesberg said. Very few primary courses document the life of this vibrant community, Giesberg said.

Giesberg is the editor of Emilie Davis's Civil War: The Diaries of a Free Black Woman in Philadelphia, 1863-1865, published in June by Pennsylvania State University Press. The book is a product of Giesberg's work with a team of students who transcribed and annotated the diaries as part of a Penn State project to digitize historical resources.

In January 2013, the team's work went live on the Web page "Memorable Days: The Emilie Davis Diaries" at davisdiaries.villanova.edu.

Davis describes her activities in short entries, some about the size of a tweet. She writes about the weather, church gossip, her dates with "gallant" gentlemen, feuds with friends, and sewing a wedding dress for a client into the early morning.

Yet the gravity of the times peeks through.

Davis worries about her brother, who was drafted to fight with the U.S. Colored Troops, regiments of the Army composed of African American soldiers. She also frets about her father, who lived in Harrisburg when Confederate forces invaded Pennsylvania before the Battle of Gettysburg.

On April 15, 1865, Davis grieved with the nation: "Very sad newes we received this morning of the murder of President the city is in deep mourning. . . ."

Later, she describes her efforts to view Lincoln's body while it lay in state at Independence Hall: "I got to see him after waiting tow hours and a half it was certainly a sight worth seeing."

There is little analysis or politics in Davis' writing, just the facts of her life. It is that ordinary quality that Karsonya Wise Whitehead, an assistant professor of communications at Loyola University Maryland in Baltimore, finds fascinating.

"She didn't involve herself every day in a fight. She was going to school, working, spending time with friends, dating, giving insight into the social culture of young free black people," said Whitehead, author of Notes From a Colored Girl: The Civil War Pocket Diaries of Emilie Frances Davis, published in May.

Whitehead began scouring the diaries as a graduate student in 2005. She called it "a search and rescue mission to bring voices like Davis' to light." No photos of Davis have been discovered.

In census data, Davis is identified as mulatto, one of four children born to Charles and Helen Davis, said Whitehead, coeditor of Rethinking Emilie Francis Davis: Lesson Plans for Teaching Her 1863-1865 Civil War Pocket Diaries, a guide for teachers that is scheduled to be released in two weeks.

At one time, Davis lived with her brother at Ninth and Rodman Streets, in a large African American neighborhood. She attended church (at what is now the First African Presbyterian Church), school (the Institute for Colored Youth, now Cheyney University), and musical performances (the former Concert Hall) in her community.

Davis eventually married and had at least five children.

"It makes your mind reel, thinking about what her life was like," said Lee Arnold, senior director of the library and collections at the Historical Society.

Davis' diaries helped inspire Mary L. Hagy of Queen Village to write "In Sun and Snow," a short play performed as part of a Juneteenth celebration in 2006 at venues including the Walnut Street Theatre.

Kalela Williams of Mount Airy, program coordinator of One Book, One Philadelphia, is writing a novel based on Davis' life.

Davis died in 1889 at 51 and is buried in an unmarked grave at Eden Cemetery in Collingdale.

In Maryland, Whitehead has developed the Emilie Frances Davis Center for Education, Research, and Culture, a platform from which she is encouraging young people to tell their own stories.

"People feel like their lives are not worthy of being recorded if they are not doing Dr. King-type work," Whitehead said. Channel Davis and "claim your own story," Whitehead said. "Your life is worthy because it is your life."