'Recovery homes' are often unlicensed and unhealthy

In one case, a drug counselor at a Center City clinic rents homes deemed "unfit for human habitation" to methadone patients.

JEFFREY Jackson, as an addictions counselor, is supposed to save the city's most desperate. At the same time, outside of his job, he's renting rooms to them in hazardous homes that the city has deemed unfit.

In a side business he dubbed "Dignity Recovery," Jackson for years has run shabby "recovery homes" that house former and current clients treated at Addiction Medicine & Health Advocates (AMHA), where he works, and others.

He collects rent even though he has no rental license or zoning permit, and housing officials have repeatedly deemed the properties, including one crammed with as many as 34 beds, "unfit for human habitation," according to city records.

The city's Department of Licenses and Inspections seems unable to stop Jackson from renting rooms. After L&I cites the homes for numerous violations, Jackson opens others elsewhere. He has run at least seven homes, including four on Clearfield Street in Kensington, according to city records and neighbors.

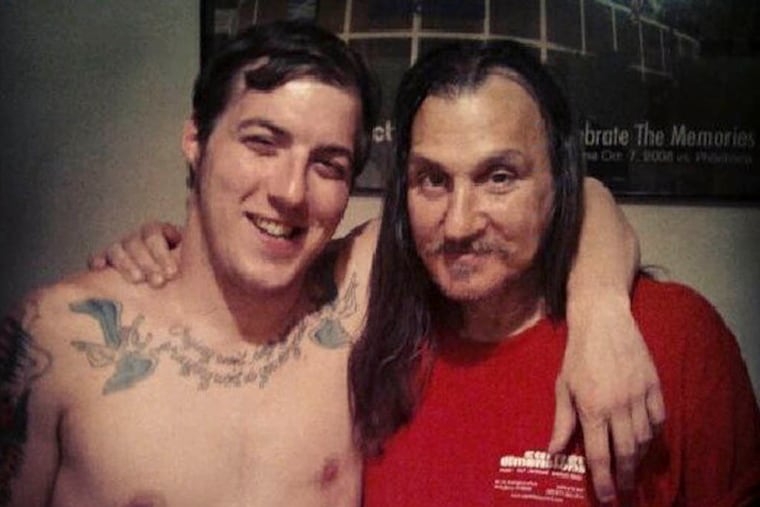

A little more than four months ago, an AMHA client, Michael Berk, died of a drug overdose inside a Jackson-run home on Kensington Avenue near Cambria in Kensington.

The graffiti-scrawled, three-story house with a metal grate shielding the first floor sits under the thunderous El train at ground zero of open-air drug sales in the city.

To live there, Berk paid Jackson nearly $600 a month in rent and food stamps, according to his son, Jordan Berk.

"For a rehabilitation drug-treatment counselor, to set someone up in a place like that is . . . setting him up to fail," Jordan Berk said.

L&I moved to close the house late last month. An L&I sign on the door dated Aug. 21 read, "Cease Operations/Stop Work Order . . . This premise is ordered vacated immediately of all occupants."

But last week when reporters visited the property, the sign was still on the front door, but the door was ajar and people were coming and going.

Jackson's operation is far from unusual. City officials say the house on Kensington Avenue is one of hundreds of unlicensed, for-profit recovery homes in Philadelphia. Landlords collect rent, often in the form of Social Security disability benefits and food stamps, as part of this underground economy. The conditions of the homes vary, as do the services provided.

Some have tough-love staffers who encourage tenants to attend programs to stay sober and do urine screenings. Others, some of which have bloomed inside abandoned homes, devolve into drug dens and brothels.

Those who work in the field of addiction treatment acknowledge that even the worst recovery homes often serve as a safety net for those who are alienated from their families and have nowhere else to go.

To Jackson's supporters, he is a do-gooder who tries to help hard-core substance abusers, "the worst of the worst," and struggles to collect rent and pays utility bills out of his own pocket.

To Jackson's critics, he's a money-hungry manipulator who puts at-risk substance abusers in unfit, unsafe homes and uses his drug counseling job to find tenants.

'He got me methadone'

The Daily News gave Jackson, 46, repeated chances to tell his side - by phone and once in person. He declined to comment other than to describe himself as a "professional" and his properties as "rooming homes," not recovery houses.

During the last phone conversation on Friday, Jackson told a reporter, "I have nothing to say. Whatever you gotta do, you gotta do. I don't think you were fair."

Jackson doesn't have the required licenses, including a housing rental license and business privilege license (now called a community activity license), to run either a rooming house or a recovery home. Nor does he have zoning permits, city records show.

How much Jackson has profited from the homes is unclear.

Former and current Jackson tenants told the Daily News that he charged roughly $400 to $600 a month, including about $190 in food stamps. Tenants said he provides them three meals a day, although some groused about the quality.

They said that some of Jackson's tenants relied on AMHA's outpatient-treatment clinic, on Market Street near 9th, for their daily dose of methadone. Methadone is a synthetic opioid mostly used to reduce or mask the debilitating, flu-like symptoms of heroin withdrawal.

One woman, who was living in a Jackson-run home on Kensington Avenue in June, likened methadone to "liquid handcuffs."

Another woman, Diane Sanford, 64, a former Jackson tenant who still gets her methadone (which she calls "juice" from AMHA, said she feared she would die without her daily dose.)

Sanford, who said she had been a heroin addict since age 17, arrived at AMHA's doorstep about five years ago because she was desperate for methadone. Sanford had been rejected from other clinics.

Jackson, who is an intake counselor for AMHA's "methadone maintenance program," helped her, Sanford said.

"He got me methadone," she recalled in a recent interview. "He kicked ass to get me on the program."

For a while, she said, her life was manageable, but then she and her boyfriend lost their home.

"I have no place to go. I'll be living under the bridge," Sanford said she told Jackson. "He said, 'As luck would have it, I have some places.' "

She and her boyfriend, Kurt Albertelli, agreed to pay Jackson about $400 a month to rent a room in a house on Allegheny Avenue near F Street in Kensington. She said she was one of 12 people living there. It wasn't long before she felt like a hostage, she said. She worried that if she failed to pay rent, her methadone would be withheld.

"He told me, 'I don't go through the system. I have my own system,'" Sanford said. "I was intimidated and I was afraid."

Robert Holmes, AMHA's executive director and Jackson's boss, said Jackson does not have sole discretion over who gets accepted into the clinic's methadone program.

Jackson simply "presents the case to a supervisor and a decision is made among our staff, including the medical director," Holmes said.

Jackson has worked at AMHA, which receives roughly $2.4 million a year in federal funding, for eight years.

Holmes described Jackson as a "responsible person who does his job well."

Holmes said he knows that Jackson rents out housing, adding, "We don't tell him what to do outside working here."

Likewise, patients have free choice, Holmes said.

"Our patients have a right to live wherever they want. If they choose to live there, that's their decision," Holmes said.

Holmes said he was mindful of potential pitfalls: "We discourage people who are interviewed or counseled to live in one of his properties because it could be viewed as a conflict of interest. [Jackson] knows he should not be referring people directly to his properties. It's that simple. I'm real clear about that."

Fred Way, executive director of the Pennsylvania Alliance of Recovery Residences, said it is a conflict, especially since Jackson can be privy to the government financial assistance the clients receive.

"[Jackson] is working at an outpatient program. He's using that as [a] feeder. That's exactly what he's doing," Way said. "What he is doing is wrong."

City Councilwoman Maria Quinones-Sanchez represents the 7th District, which is chock full of recovery homes, particularly in Kensington and Frankford.

She said she was not aware that Jackson worked as an addictions counselor until a reporter told her.

"That's definitely a conflict," she said. "Unless there is a written transparent policy, no one can measure or monitor what he's doing."

Roland Lamb, director of the Office of Addiction Services for the Department of Behavioral Health and Intellectual disAbility Services, monitors a network of treatment providers, including AMHA.

Lamb said he would look into Jackson's homes after a call from the Daily News.

The next day, while the Kensington house was still open, Lamb told the Daily News that Jackson's homes are "far below standards."

"Right now I would categorize his recovery houses as at-risk," Lamb said, meaning that "they are so far below our standards that we would not consider them to be appropriate."

Bedbugs and rats

The house at Kensington and Cambria was a persistent neighborhood nuisance. Over a recent 12-month period, police were called there 20 times for a variety of complaints.

Former tenants said the house was infested with bedbugs and rats. The door, with the house number scrawled in black marker, was unlocked during each visit by the Daily News.

Earlier this summer, a woman, who identified herself only as "Rose," told Daily News reporters that she is the house manager and was cooking pork chops. She referred all questions to Jackson, whom she described as a good man who just wants to help people.

L&I last inspected the property in May when it appeared that some repairs had been made to fire-damaged areas, according to Ralph DiPietro, deputy commissioner.

Jackson had until Aug. 21 to vacate the property because he had failed to obtain required licenses and permits, DiPietro said.

"We try to give them as much time, as much advance notice as possible, because we just don't want to throw people out on the street," he said.

The Kensington Avenue property and the one on Allegheny Avenue, which Jackson still runs, are owned by Mark Nuzzo and Joseph Bennett, of Sewell, N.J.

Neither returned repeated calls from the Daily News.

For years, serious L&I violations have piled up on both properties. Inspectors found multiple code violations, including an inoperable fire-alarm system, and none of the required licenses or permits.

In 2010, L&I found 34 beds in the Kensington Avenue home. And in 2009, inspectors counted 24 beds in the Allegheny house, which at the time inspectors said was "dangerous to human life."

The L&I case file cited the property owners and Jackson.

Jackson himself has been down the road of recovery. He used to be addicted to cocaine and heroin, according to a 2009 interview with Philadelphia Weekly. He has a criminal record that includes convictions in 2000 for theft in New Jersey and drug possession in Philadelphia.

He earned his master's degree in behavioral studies, became an addictions counselor, first at Girard Medical Center and later at AMHA.

In 2011, Jackson, who lives in a modest three-bedroom townhouse in the Northeast, filed for bankruptcy, listing his 2010 AMHA earnings as $46,660.76.

The filing lists $226,703.38 in assets and $561,146 in liabilities. The document makes no mention of Dignity Recovery, which he founded in June 2008, state records show.

Sanchez said her office received complaints about Jackson when he ran a recovery house on Harrison Street near Hawthorne in Frankford.

"He made statements and commitments that he didn't fulfill. The community pushed back," she said.

Carl Williams, who rented the large home on Harrison Street to Jackson, said Jackson started out with good intentions, but without city funding and support, he struggled to pay rent and utilities.

Williams said he wanted $4,000 a month for what he described as an 11-bedroom house, but Jackson never once paid the full amount.

Most of the people who Jackson placed at the home were drug addicted and on methadone, Williams said. The house was set up to accommodate women and children.

"A lot of women came to him for shelter and he tries to put them up. He stuffs them in; even if it's illegal, he'll find them a cot," Williams said.

Jackson is in a unique spot as an addictions counselor and the city should help subsidize his recovery homes, according to Williams.

"A guy like that has that many people - that many addicts at his grasp - all the addicts in the city know him," he said. "If he could change 10 percent of them, that would be a great big help to the city even if he [is in violation of city regulations.]"

Overdosed on heroin

Some time after L&I shut down the house on Harrison Street, Jackson popped up at the Kensington Avenue address.

A fire damaged the roof of the Kensington Avenue property in 2011 and the agency deemed it unsafe and in danger of collapse.

"While the dwelling is designated as unfit for human habitation, you are denied the right to collect rent or admit new tenants," L&I wrote in a July 2011 violation notice sent to Nuzzo and Bennett, and to Jackson as executive director of "Dignity Recovery."

More than two years later, on March 18, 2014, L&I's Code Enforcement Unit sent a more urgent notice: "[The house] presents an immediate hazard to safety and must be evacuated."

Jackson continued to run the place. Michael Berk, 58, was one of the tenants and Jackson had been one of his longtime counselors.

Every morning about 6:30, Berk would go downstairs for a cup of coffee and a cigarette. There in the kitchen, another tenant, Stacey Malseed, said she routinely joined him.

On April 28, Berk didn't show up. At 7 a.m., Malseed went upstairs and pounded on his door. No answer.

In a panic, she busted open the door and found Berk sprawled face down on the bed. His body was swollen, stiff and cold.

"I moved his hair away and there was blood on his mouth," Malseed said. "It was Mike and I just never seen nothing like that. I was traumatized. It took a good three weeks to get the image of him out of my head."

The cause of death: drug intoxication, according to the Medical Examiner's Office.

Berk, according to his son, Jordan, had overdosed on heroin and Xanax, combined with methadone that he received from Jackson's clinic.

"When my dad would complain about the conditions, Jeff would blow smoke up his ass and said everything was going to be OK," Jordan Berk said.

"It never was."