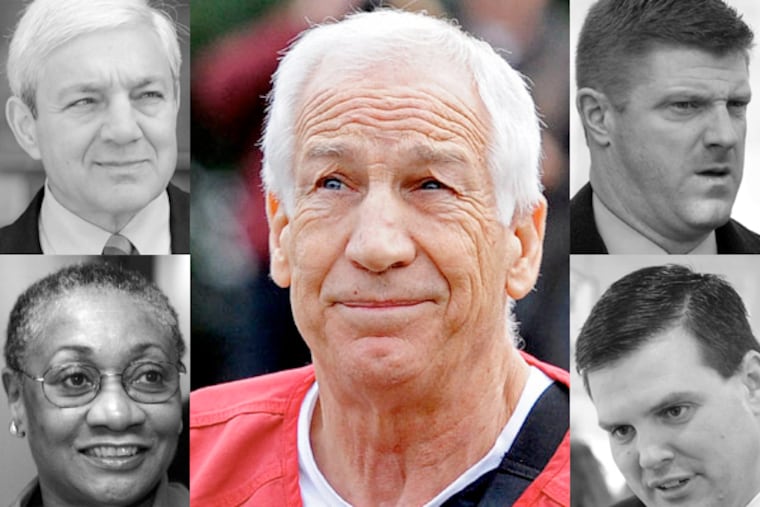

Suits from Sandusky scandal linger on

A complaint filed this week served as a reminder that the legal battles over the Jerry Sandusky child sex-abuse scandal are far from over.

A complaint filed this week served as a reminder that the legal battles over the Jerry Sandusky child sex-abuse scandal are far from over.

At least seven civil cases as well as criminal complaints against three former Pennsylvania State University administrators are pending.

A January settlement between the NCAA and a Pennsylvania state legislator restored 111 of former head football coach Joe Paterno's wins and replaced the consent decree that defined penalties against the university. But for key participants, the fights continue. And when they may end is unclear.

Former university president Graham B. Spanier filed a defamation complaint Wednesday against Louis Freeh, the former FBI director and author of a report on the Sandusky scandal that served as the basis for the now-superseded consent decree.

Subpoenas for documents are out in some of the cases. Those can precede a settlement, said Matt Haverstick, who represented state Senate Majority Leader Jake Corman (R., Centre) in his successful action against the NCAA.

"In general, if one side in a litigation or the other is concerned about documents that it may have to turn over, that may encourage settlement," he said.

Spanier and former assistant coaches Mike McQueary, William Kenney, and Jay Paterno, the former coach's son, seek damages.

Victory in other cases may be more symbolic. A university trustee is a plaintiff in the Paterno family suit, and other trustees, such as Anthony Lubrano, a leading critic of the report and decree, would consider it a win if the NCAA retracted the conclusion that Penn State's "culture of reverence for the football program" allowed Sandusky to flourish.

"Penn State has never lacked athletic integrity," Lubrano said.

Though the consent decree between the NCAA and Penn State has been superseded, the NCAA has not withdrawn its conclusions. The Paterno family disputes the consent decree's statement that the head coach, who died in 2012, covered for Sandusky to protect the school's football program. The suit seeks to do to the consent decree what it temporarily did to Paterno's wins - wipe it from the records.

Sandusky is serving a 60-year term after his 2012 conviction for sexually abusing 10 boys.

The NCAA, Penn State, and most university trustees contacted declined to comment for this article. Pepper Hamilton, which bought Freeh's law firm, also did not respond.

The 2012 Freeh Report looms large over the suits. Paterno, Spanier, former vice president Gary Schultz, and former athletic director Tim Curley showed a lack of empathy toward victims and concealed Sandusky's activities to prevent bad publicity, it concluded, and "failed to protect against a child sexual predator harming children for over a decade."

Only Spanier has sued Freeh, but suits from the Paterno family and two assistant coaches focus on Freeh Report language used in the consent decree. The report was biased, inadequately researched, and reached conclusions not supported by evidence, the suits claim.

Here is where the suits stand:

Paterno family v. NCAA. The Paternos are suing the NCAA, president Mark Emmert, and former chairman Ed Ray for statements in the consent decree that the coach helped to cover for Sandusky. The family is not seeking money, spokesman Dan McGinn said. It wants Joe Paterno's reputation restored.

"You can never undo all the damage that they did, not to Joe Paterno, not to the other individuals," McGinn said.

Penn State is also listed as a nominal defendant, and Jay Paterno and William Kenney are also plaintiffs.

Jay Paterno and William Kenney v. Penn State. Both men, let go in the months after the scandal broke, have a separate federal suit that takes issue with the report's claims that "some coaches" ignored warning signs about Sandusky. Penn State had the right to dismiss them but was wrong to later disparage them by quoting from the consent decree without letting them respond, both men say. Both say it has hurt their careers.

"The lawsuits have been very, very productive that way in uncovering the truth, and that's really what we're all about," Paterno said.

The university filed a motion to dismiss the federal suit, denying the two coaches' claims.

McQueary v. Penn State. Former assistant football coach McQueary's suit against the university claims he was defamed and punished for blowing the whistle on Sandusky. While a graduate assistant coach in 2001, McQueary says, he saw Sandusky engaged in "illegal sexual conduct" with a young boy in a Penn State locker room showers. McQueary's suit says he shared what he saw with Joe Paterno, Schultz, and Curley.

McQueary eventually was let go, and argues his treatment by the university came because he cooperated with criminal investigators. His lawyer declined to comment.

The university also denies McQueary's claims.

Spanier v. Freeh. Spanier's direct challenge to Freeh this week argued that the report was commissioned to falsely point the finger at him.

"Dr. Spanier was never aware of any child-abuse accusations," the suit states, "and therefore never could have concealed such allegations."

Spanier also alleges the report led to criminal charges filed against him in 2012.

The report was direct and responsible, argued Freeh's lawyer, Bob Heim.

"Despite all his 'sound and fury,' the Freeh Report stands unchallenged on its facts," Heim said.

Others. There are three other suits pending. Two suits filed by Sandusky victims, one in federal court and the other in Philadelphia Common Pleas Court, are in the discovery phase. A suit by Schultz against former Penn State lawyer Cynthia Baldwin has seen no activity since 2012.

The criminal case. Spanier, Schultz, and Curley are charged with concealing information about Sandusky's crimes and lying to investigators. A trial has not yet been scheduled, and the men say they are innocent.

They are challenging a judge's decision that Baldwin did not violate attorney-client privilege when she testified in grand jury hearings. A judge ruled that Baldwin was representing the university and the three men as employees of the school, not as their personal counsel. The defendants argue that they thought Baldwin was their lawyer during their grand jury testimony, and that she did not tell them otherwise. They call her testimony a violation of attorney-client privilege.

In February, Spanier also filed a sealed appeal for extraordinary relief with the Supreme Court. The details are not public.

That application has the potential to finally move the criminal cases forward, said Francis Chardo, first assistant district attorney in Dauphin County, who has assisted the Attorney General's Office with the prosecution. It is possible, Chardo said, that the high court could address all the issues under appeal, resolving them and moving the case closer to trial.

610-313-8114 @jasmlaughlin