Yale's Class of 1964, always on the cusp of change

The men of Yale University's Class of 1964 graduated from a citadel of tradition into an America that was about to change radically - and would revolutionize many of their lives as well.

The men of Yale University's Class of 1964 graduated from a citadel of tradition into an America that was about to change radically - and would revolutionize many of their lives as well.

"As straight as we were, and as socialized as we were in the experiences and expectations of post-World War II . . . we couldn't take a straight line from there as a group," says Howard Gillette Jr., author of the new book Class Divide: Yale '64 and the Conflicted Legacy of the Sixties (Cornell University Press).

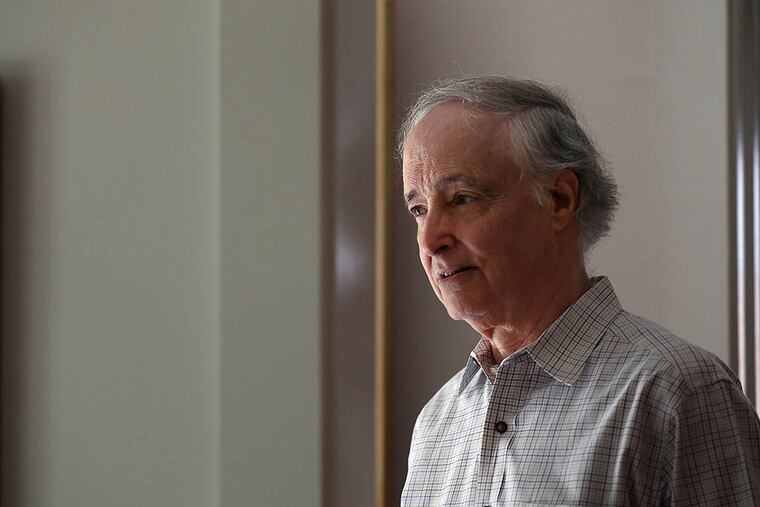

A retired Rutgers-Camden professor of history and a progressive urbanist whom I've known and respected for 20 years, Gillette, 72, was a self-described "Lincoln Republican" from small-town Illinois when he entered Yale in 1960.

Like him, most of the 1,000 freshmen were white, Protestant, and privileged; they had been born, bred, and prep-schooled to serve as leaders of the nation their fathers and grandfathers had helped to make.

But as Gillette's book shows, within just a decade of graduating, some members of the class had gone in unexpected directions, some were holding fast to old-school convictions, and others had become unmoored by the cultural upheavals of the late '60s and early 1970s.

Events in the book "are part of my own story," says Gillette, who lives in Haddonfield with his wife, Margaret Marsh, Distinguished Professor of History at Rutgers-Camden.

The author of Camden After the Fall and three other books, Gillette began working on Class Divide six years ago.

He was prompted in part by the story of classmate Stephen Bingham, with whom he served (along with Joseph Lieberman, a future senator and vice-presidential candidate) on the staff of the campus newspaper, the Yale Daily News.

A prominent civil-rights attorney, Bingham was charged with smuggling a gun into a California prison where a 1971 riot claimed six lives, including that of his client, an activist inmate. Bingham fled the United States and lived in Europe before returning home to face trial; he was acquitted in 1986.

"It was fascinating that one of our own would become a fugitive from justice for 13 years," says Gillette, contrasting Bingham's trajectory with that of their classmate William Bradford Reynolds.

A scion, like Bingham, of a noteworthy New England family, Reynolds headed up the civil-rights division of the U.S. Department of Justice under President Ronald Reagan. He later become a lightning rod for criticism of the administration's approach to enforcement of civil-rights laws.

"That two such well-educated men of privilege . . . each idealistic and responsible in his own way, could end up on such far ends of the civil-rights spectrum would have been surprising in 1960 . . . [but] confirms the continued dilemma of race in America," the author writes.

The civil-rights struggle was "absolutely central" in creating the divide of his book's title, Gillette tells me.

He notes that Lieberman and other classmates went to Mississippi to help secure black voting rights in 1963, evidently inspired by the emerging ferment on campus, as well as by Yale's long-standing culture of public service.

Having graduated before the Vietnam War and the sexual revolution roiled campuses nationwide later in the decade, others among the 110 classmates Gillette interviewed for the book spoke of "missing" the '60s.

But he discovered a number of Class of '64 members had thrown themselves into the era's famous sex, drugs, and rock and roll. Others emerged as champions of women's equality, gay rights, and the environment, and still others deepened the conservatism of their youth.

John Ashcroft, Yale '64, served as George W. Bush's attorney general. And in an apt illustration of the divisions among Yale '64 graduates, Lieberman voted against his classmate's confirmation in the Senate.

Bush, like his father, also was a Yale man (Class of 1968), which attests to the role the 314-year-old university continues to play in American life.

The divide endures as well: Gillette says the GOP in which he once was active long since abandoned the progressive values he had grown up with.

But in his conclusion to Class Divide, he notes that regardless of divergent political philosophies, the subjects of his book "did not remain on the sidelines" after leaving the university.

The Yale experience still resonates for alums like Gillette, whose professional life as an urban historian culminated, in a sense, in Camden.

But his world view was nurtured, and his career took root, in New Haven.

"Yale," Gillette says, "opened the world to me."