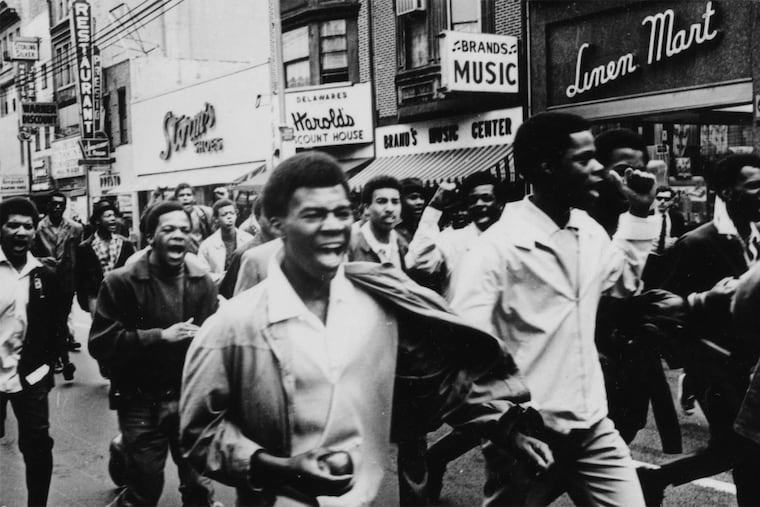

Did 1968 occupation of Wilmington spark decline?

For more than 9 months in the 60s, National Guard troops patrolled the city the longest military occupation on U.S. soil since the Civil War. Scars remain.

THEY CALLED themselves "the Goon Squad" - a kind of A-Team of strong, burly African-American men who drove the streets of Wilmington's predominantly black neighborhoods in the late 1960s looking for early signs of gang violence and telling young people to keep it cool.

Herman Holloway Jr., a veteran community activist in the Delaware city who helped organize the Goon Squad when he was in his early 20s, recalls that the team included a former Navy heavyweight boxing champ and a man who moved broken-down cars with his bare hands. But even these guys weren't enough to keep a lid on the tensions that erupted on the night of April 8, 1968 - four days after the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in Memphis.

That afternoon, Holloway and his band of heavyweights were assaulted by a group of teens throwing a brick through the back window of their Cadillac Fleetwood. A few hours later, local ministers and the NAACP called a meeting at the YMCA seeking to calm things down, but the youthful activists and rebels would have none of it. The pastors and black community leaders were cursed at and called "Uncle Toms."

"After that, they opened the doors and a lot of them went running down the hall yelling, 'Burn, baby, burn!' " Holloway recalled. "That was the night they set the West Side on fire."

Almost every major American city endured rioting in the late 1960s, but Wilmington turned out to be different - very different. On one hand, the violence after King's murder was contained mostly to arson and some looting, without the bloodshed experienced in nearby Baltimore, where six people were killed during unrest that April.

On the other hand, in a sign of some of the deep divide and mistrust in Delaware that lingers to this day, the white Democratic governor down in Dover decided to send in the National Guard - and then kept troops on the streets of Wilmington for nine long months, the longest military occupation of a U.S. city since the Civil War.

Today, nearly a half-century later, as civic leaders protest Jada Pinkett Smith's planned ABC-TV drama series set in Wilmington called "Murder Town" - and as the streets where armed troops once cruised in open jeeps ("the Rat Patrol," many locals called them) struggle with rising murder rates and the entrenched drug trade - some wonder whether the epic turmoil of 1968 sowed the seeds for the long-term decline of Delaware's largest city.

"It had its impact," said James Baker, who was working in the streets to reduce gang violence in 1968 and later served as the city's mayor from 2001 to 2013. "But there were a lot of things going on causing problems . . . There still are."

Indeed, Baker remembers the riot and lengthy occupation as one thing that drove working-class families away from Wilmington's West Center City and other inner-city neighborhoods, but there was also the accelerated loss of manufacturing plants throughout the 1970s as well as the construction of Interstate 95, which ripped apart entire blocks. Many large single-family homes that remained were divided into smaller apartments, for a less-rooted, poorer population.

Not that Wilmington's lower-middle-class areas were paradise 47 years ago. In a state where slavery took place and was hotly debated before the Civil War, blacks who lived in the Delaware city had been feeling the pain of discrimination in housing and the labor market even before the shock of King's assassination.

In the end, though, it may have been old-fashioned election-year, law-and-order politics that drove Delaware's then-incumbent Democratic governor, Charles Terry, to continue the state of emergency that was declared in the April 1968 riot for the rest of that tumultuous year. Terry, a rural down-stater, seemed convinced that Wilmington was on the verge of a major insurrection.

"He had the wrong people telling him the wrong things," Baker recalled. In fact, the nine-month occupation only made things worse on the West Side and in other predominantly black neighborhoods in Wilmington. The troops were mostly young men from the farm belt of lower Delaware with no experience in urban policing, and several incidents escalated into what locals saw as needless violence. But what really grated on residents was the accompanying curfew that restricted their movement at night, preventing some from even getting to their jobs.

Evidently, the majority of Delaware voters agreed that the lengthy military occupation was a dumb idea. That November, Terry was voted out of office and replaced by Republican Russell Peterson, who took the oath of office at midnight Jan. 21, 1969, and had the National Guard out of Wilmington by 3 a.m.

But the memory still burns for those who lived through the occupation. "It sent a shock wave through the social-service agencies . . . and the city as a whole," Baker recalled. "People said, 'What are we doing?' "

215-854-2957

On Twitter: @Will_Bunch

Blog: ph.ly/Attytood.com