Towing your car is his dream job

If fame is measured in name recognition, then Lew Blum must be considered one of Philadelphia's biggest celebrities.

If fame is measured in name recognition, then Lew Blum must be considered one of Philadelphia's biggest celebrities.

Not the most popular, mind you. He is not liked, not even a little, judging by the torrent of vitriol heaped on him in online Yelp reviews. "The lowest of the low," is one of the nicer comments you'll find there. But it's a name guaranteed to evoke a nod of recognition, and no small shiver of fear, by anyone who parks on the streets of Philadelphia.

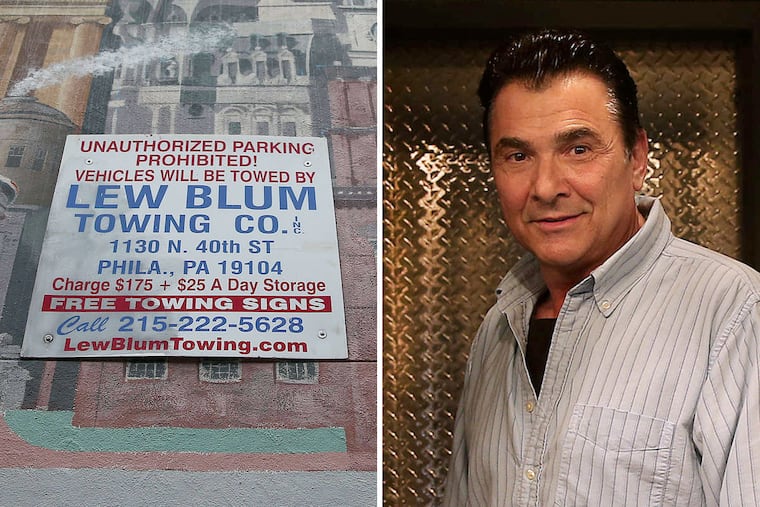

The name "Lew Blum" can be seen in large, blue capital letters on the 36-by-36-inch signs that hang by the thousands in parking lots, on garage doors, and near driveways and loading docks, from Plymouth Meeting to the Delaware state line, giving fair warning that UNAUTHORIZED VEHICLES WILL BE TOWED. Even for those who get off with the minimum payment - $175, plus $25 a day for storage - an encounter with a Lew Blum tow truck is never a good experience.

Who is this Lew Blum guy, and why did he choose an occupation that so many people despise?

"Lew Blum" signs have been a fixture of Philadelphia streetscape for so many decades that it is hard to imagine that an actual Lew Blum exists in human form. The name sounds more like a made-up advertising character, the Betty Crocker or Colonel Sanders of Philadelphia towing. "Lew Blum towing is as much a part of Philadelphia history as Benjamin Franklin," George Polgar, a former nightclub manager who used to help customers rescue their cars, wrote in a Facebook comment.

But there really is a flesh-and-blood Lew Blum, and he can be found behind a bulletproof window, jammed inside a closet-size vestibule where every inch of the floor, walls, and ceiling has been lined with indestructible diamond-plate steel paneling.

"Towing," Lew Blum tells a reporter who managed to penetrate the inner sanctum of his Mantua headquarters at 40th and Girard, and to make it up an unlit staircase to a spacious office overlooking a mini-mart and several windowless houses, "is my dream job."

Few know the deep passions, intensity of purpose, or long-running feuds that inspire the man whose email handle is "hookasaurus."

Blum, who is a youthful 60 with jet-black hair, and who wishes it to be known that he is single, is actually third-generation towing royalty. As a child growing up at 38th and Lancaster, in a house demolished to make way for Presbyterian Hospital's expansion, he only had to walk a block to his grandfather's Powelton Avenue garage and gas station. The second of eight children in a half-Greek, half-Jewish family, Blum was named after the towing patriarch, Lew Smith.

"My mother worked in the office when she was pregnant with me, so I must have heard the tow trucks from the womb," explains Blum. His father was often absent, and he just wanted "to be with Grandpop."

At 8, he was "hooking" cars for his grandfather's business. At 13, he was skipping school to drive the trucks. Blum says his grandfather routinely paid off the truant officer from the Drew School (recently demolished to make way for a University City Science Center development) to look the other way. By 14, he had dropped out to work full time. And when the business was passed to an uncle, George Smith, another towing celebrity whose name is plastered across the city, Blum was a mainstay.

After they had a falling-out in 1976, Blum found himself adrift, responding to routine breakdowns for another garage. But it was never "wreck-chasing" that interested him. Blum considers his work a calling; it's his job to fight parking anarchy by keeping people from leaving their cars where they're not supposed to, on the private property of others.

This is something that the "violators" who arrive in his steel-plated vestibule to retrieve their towed cars fail to understand, especially when they are in the first stage of fury and spewing unprintable words at him.

They think they are his customers, explains Blum, who is 6-foot-1, 205 pounds, and carries a gun. They are not. It's the property owners who post his signs, at no cost to themselves, that Blum serves. He has made it his life's work to plant as many "Lew Blum" signs as he can around the city. "It is a good feeling to see your name on 5,000 signs," he says, beaming.

Sometimes, Blum gets a little carried away, according to others in the towing business, posting his signs where he hasn't been invited.

Blum, who taught himself management skills by reading the self-help work of Dale Carnegie and Norman Vincent Peale, insists he is just trying to build his business. It bugs him to no end that developer Bart Blatstein hangs George Smith signs on his properties. Unlike Lew Blum Towing, that firm no longer has a George Smith behind it. The company was sold out of the family after the death of Blum's uncle. Both firms, incidentally, get a one-star Yelp rating.

In a parking-obsessed city, it is not surprising that violators nearly always insist that their cars have been wrongly towed. They frequently accuse Blum of outright theft. Blum maintains that his tow operators follow a strict protocol, photographing each vehicle before it is hooked and checking in with police. He won't say how many tow trucks he owns or how many cars he hooks a day.

Don't get him started about who he thinks the real cheaters are. He faults the police, the politicians, and, most of all, the Philadelphia Parking Authority for interfering with the legitimate work of private towing businesses. He reserves his greatest ire for the parking authority, which, he claims, misleads drivers by not posting their fees for releasing a towed car.

"Why does City Council require private [towing companies] to have these big signs, and not the parking authority?" he fumes. If their signs were bigger, there's no way that PPA would be towing what Blum estimates is 300 cars a day, he said. "It's not called the 'Towing Authority.' "

In an instant, Blum reverts to his jovial self, talking about his beloved nieces and nephews. When he is not hooking the cars of violators, he likes to take the children to Diggerland in South Jersey, where they can operate real backhoes, excavators, and dump trucks. Unfortunately, the amusement park has yet to include a tow truck.

215-854-2213@ingasaffron