In Pa. and elsewhere, death penalty is dying a slow death

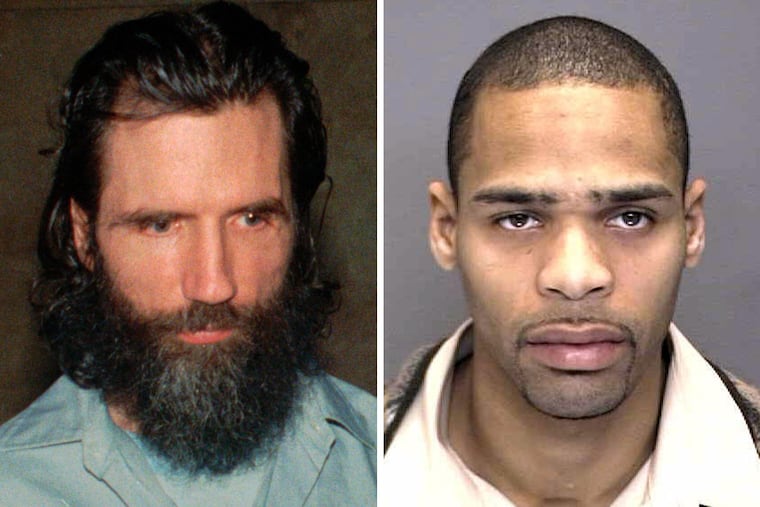

The crime was horrific: LaQuanta Chapman fatally shot his teenage neighbor, then dismembered him with a chainsaw. The Chester County District Attorney's Office promised it would seek the death penalty - and it delivered.

The crime was horrific: LaQuanta Chapman fatally shot his teenage neighbor, then dismembered him with a chainsaw.

The Chester County District Attorney's Office promised it would seek the death penalty - and it delivered.

Chapman was sent to death row in December 2012. But he remains very much alive, and two weeks ago the state Supreme Court reversed his death sentence, citing prosecutorial error.

Chapman is just the latest example of a death-row inmate spared execution.

In fact, no one has been executed in Pennsylvania since Philadelphia torturer-murderer Gary Heidnik in 1999. And he requested it. He is one of only three prisoners put to death since the reinstatement of the death penalty in 1976.

In Pennsylvania and in other states around the nation, the death penalty - once a hot-button political issue - has been dying a quiet death. Experts cite a variety of reasons, including a general decline in crime nationwide that has turned voters' attentions elsewhere.

District attorneys and other law enforcement officials continue to advocate for it, but as a political issue, it has all but disappeared.

"Let's face it, how many people actually get put to death?" said G. Terry Madonna of Franklin and Marshall College, calling the death penalty "virtually nonoperative" in Pennsylvania. "In many states, it's a dead letter."

Gov. Wolf last year imposed a moratorium on executions pending a bipartisan committee's report on the commonwealth's use of capital punishment. The report, more than two years overdue, is looking at costs, fairness, effectiveness, alternatives, public opinion, and other issues.

The committee, formed in 2011 during Gov. Tom Corbett's administration, has been collecting data with Pennsylvania State University's Justice Center for Research, which has just begun to analyze the information. The basis for the center's death-penalty analysis will be 1,106 first-degree murder cases completed between 2000 and 2010, said Jeff Ulmer, a Pennsylvania State University professor working on the analysis.

The committee's report should follow before the end of the year, said Glenn Pasewicz, executive director of the state commission that oversees the committee.

Richard Long, executive director of the Pennsylvania District Attorneys Association, which supports the death penalty, said the report needs to come out as soon as possible.

The moratorium, he said, "becomes less and less temporary with every day that passes."

State Sen. Stewart Greenleaf (R., Bucks), one of the leaders of the state task force, stressed the need for it to be thorough.

"I think it's going to be a landmark review of the death penalty, certainly in Pennsylvania, maybe nationally," he said.

The American Bar Association and the Pennsylvania Supreme Court Committee on Racial and Gender Bias in the Justice System are among the groups that have criticized the inequality of Pennsylvania's capital punishment system and have urged changes.

About 150 death sentences and capital convictions in the state have been overturned in the post-conviction process, according to the Death Penalty Information Center, a nonprofit group critical of the ways in which the death penalty has been administered. Of those, 120 have had new sentences imposed.

But juries continue to issue death sentences. Pennsylvania has 180 people on death row, the fifth largest number in the country. The 178 men and two women are housed in three state correctional institutions.

Nationwide, the death penalty has continued to fall out of both favor and public consciousness. In the 1988 presidential election, Democratic nominee Michael Dukakis was famously asked whether he would oppose the death penalty even in the hypothetical case of a man who raped and murdered his wife. Among issues raised in the 2016 presidential campaigns, the death penalty hasn't been one of them.

In addition to Pennsylvania, governors have imposed moratoriums in Washington, Oregon, and Colorado, according to the Death Penalty Information Center. Nineteen states have gotten rid of the death penalty, including New Jersey, which spiked it in 2007.

All five candidates vying to succeed Kathleen G. Kane as Pennsylvania attorney general support the death penalty, saying that the law reserves the punishment for egregious murders.

State Sen. John Rafferty (R., Montgomery) opposes Wolf's moratorium, saying the governor "took a tool out of the tool belt of our prosecutors." He added that the death penalty should be used for people who kill children, senior citizens, and first responders in the line of duty.

John Morganelli, Northampton County's district attorney and a past appointee to the state Supreme Court's committee on capital cases, said the state should enforce the death penalty. But, said Morganelli, a Democrat, it also should provide more training and resources for defense lawyers handling capital cases to even the playing field for everyone.

Joe Peters, a Republican and former spokesman for Kane, echoed that sentiment, saying, "We always have to be vigilant [the death penalty] is not being imposed in a disparate fashion."

The former prosecutor said a thorough death-penalty report is worth the wait, especially because the death-row inmates still are removed from society.

Josh Shapiro, a Montgomery County commissioner and chairman of the state's Commission on Crime and Delinquency, said the report needs to come out soon to fix Pennsylvania's broken system.

Shapiro, a Democrat, said a debate over the death penalty needs to be part of a larger discussion on criminal-justice reform.

Stephen Zappala, Allegheny County's district attorney, said the death penalty must be applied in a thoughtful way. He is concerned that the death penalty is not a deterrent and does not actually bring closure to victims. Recently, his office argued a couple of death-penalty cases that went back to the trial level more than 10 years after convictions.

"That's not closure, by any means," said Zappala, a Democrat.

In Pennsylvania, hundreds of death warrants have been signed, although only three have been carried out, said Robert Dunham, executive director of the Death Penalty Information Center.

"If any other public policy had a failure rate that enormous," he said, "one would expect something would have been done about it."

610-313-8207@MichaelleBond