Rampant overtime spikes city employees’ pensions in Philadelphia

The City of Philadelphia has spent nearly $900 million in overtime during the past five years, partly as a strategy to keep costs down by hiring fewer full-time workers. But a Philly.com analysis shows the strategy is driving up pension payments to thousands of employees.

The City of Philadelphia has spent nearly $900 million in overtime during the past five years, partly as a strategy to keep costs down by hiring fewer full-time workers. But a Philly.com analysis shows the strategy is driving up pension payments to thousands of employees.

Overtime has allowed unionized municipal employees to boost their yearly pay and to inflate, or "spike," their pensions at a time when the city pension fund is less than half funded, according to the examination of 167,000 payroll records from the calendar years 2009 through 2013. The records were obtained from the city through a request using Pennsylvania's Right to Know law.

Through overtime pay, a single employee can bring in hundreds of thousands of dollars in additional retirement income. Pensions are based on an employee's three highest years of pay, excluding workers in the police and fire departments.

Many city employees are logging almost superhuman amounts of hours, year after year, the analysis found. City officials say they look at departments' overall overtime spending, though there appears to be little or no study of its short- or long-term effects on municipal finances.

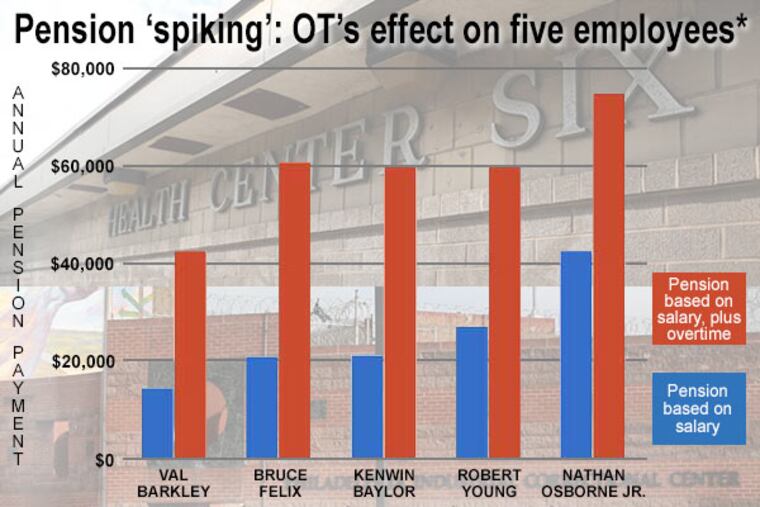

Take Val Barkley, a custodial worker for the Philadelphia Department of Health who worked more overtime hours than any other city employee last year. His base pay is $27,922 annually. But overtime boosted his total earnings to $86,500 in 2013, $78,055 in 2012 and $81,218 in 2011.

The custodian, employed by the city for six years, has accumulated thousands of hours in overtime — supplementing his base pay by $236,508 since 2009. In a conservative estimate, he would have averaged more than 50 hours beyond his regular work week in 2013 to earn $58,578 in overtime.

So if Barkley works for 25 years – never receiving a raise to his base salary or working another hour of overtime – he could retire with a $42,600 annual pension. If he hadn't worked any overtime, his annual pension would be $14,519.

The difference for Barkley over 20 years of retirement: $561,620, just from overtime.

Department spokesman Jeff Moran said the city's health centers are understaffed and custodians are often assigned to other projects. He did not provide specific records for Barkley, but added Friday that officials examined his hours and confirmed the large amounts of overtime submitted.

At Health Center #6 on West Girard Avenue, where Barkley works nights, the custodian repeatedly declined to say what duties he performed to amass so many hours: "How, what, when is not anyone's business. That's personal."

Barkley's overtime pay and pension-spiking are not aberrations.

Because the city's pension system is so complex, however, it's difficult to determine the full financial impact of overtime costs. Yet despite pursuing the overtime strategy, in part, to save on retirement costs, none of the officials interviewed - including Budget Director Rebecca Rhynhart - could point to a single cost-benefit analysis showing that the strategy works. City officials have noted that, by not hiring full-timers, they are also saving on health care costs.

Overtime pay has grown 20 percent over the five years, yet it has not raised red flags within city government.

"We look at overtime at a macro level," Rhynhart said in an interview. "I wouldn't say no one is tracking this. Each department monitors and signs off on it."

She added that $890 million over five years is not a significant portion of a city budget that runs into the billions.

Still, that nearly $900 million would have covered the school district's last two deficits of $282 million and $300 million, along with much of next year's projected $400 million hole.

Including overtime in pension calculations "substantially" increases the city's annual obligations to the Philadelphia Pension Fund, said Harvey Rice, executive director of the Pennsylvania Intergovernmental Cooperation Authority, which oversees the city's finances. Rice did not provide a firm figure, but said the overtime burden has been noted by the pension fund's actuary and other experts.

A worker need not even deliberately work overtime to boost his or her pension. Regardless, the extra hours have that effect.

"The city should initiate a systematic process for determining the optimal level of overtime for each department and hold the department accountable for their overtime use," Rice said in an email.

'10 or 12 different people who could approve OT'

Overtime permeates many city departments, yet top-down policies to regulate its use are lacking.

In the Health Department, where overtime spending increased each of the last five years, rising from $2.5 million in 2009 to $3 million last year, a deputy commissioner said that employees could have overtime approved by any number of supervisors.

"For instance, at health centers … it could be up to 10 or 12 different people who could approve OT," said Kevin Vaughan, deputy health commissioner.

"In the past, it has been that if you have several different people offered OT, there is no central place where people are looking at it," Vaughan said. He added that, after Philly.com began inquiring two weeks ago about the department's overtime and payroll management, "We are in the process of making some adjustments on that."

A half-dozen custodial workers have collected hundreds of thousands of dollars in overtime since 2009, according to city payroll data. To achieve that, those employees would have had to work an estimated 70-plus hours a week for 50 out of 52 weeks.

Said Vaughan: "If they put in those hours, they worked those hours. The issue is there are so many different people in the mix signing off, there wasn't a single person to approve it."

'I don't need a consultant to come in and tell me'

Forced overtime is a way of life within the Philadelphia Prisons System, due largely to unanticipated mid-shift responsibilities, such as transporting sick prisoners, and absences that must be covered out of safety concerns.

Supervisors will try to fill shifts with volunteers, but sometimes corrections officers are forced to work overtime.

"In slang, it's 'the hook' or 'the draft' for four hours minimum," Prisons Commissioner Louis Giorla said. "There always is because some of the OT is unanticipated. For instance, a hospital trip. An inmate has seizures and the officers that take him to the hospital have to go on OT."

Like the Health Department, however, the prison system has not done a cost-benefit analysis of its overtime.

"We haven't done that study, but I don't need a consultant to come in and tell me," said Giorla, who began his career in 1982 as a correctional officer at the House of Corrections.

He acknowledged that OT enhances his workforce's retirement pay. Prison employees, on average, made $12,820 annually in overtime each of the last five years — the highest average among city departments.

For some, the annual OT compensation was much greater.

For example, Correctional Officer Kenwin Baylor earned a total of $360,290 from overtime from 2009 to 2013 — more than any other city employee outside the police or fire departments, and far above the $203,429 he earned in base salary during those years.

Based on conservative estimates, Baylor had to average more than 40 hours of overtime per week over the five-year period.

"The people work OT," said Lorenzo North, president of the Local 159 union, which represents prison workers. "The corrections officers are the lowest paid in the state. If they were up with other corrections officers, they wouldn't have to work OT. It's tough to make ends meet."

But North also noted that forced overtime plays a large role in the amount of extra time logged by his union members.

"At the prisons, we're always short of officers. If they're not going to hire new people they're going to need OT," North said. "It could be bad because some people work mandatory OT."

Prison employees dominate the list of 898 "non-uniformed" employees who collected at least $100,000 in overtime since 2009. Seventy-three prison workers earned more in overtime than they did in base pay during the five-year period, Philly.com's analysis found.

Lots of OT = much bigger pension

One thing is for certain: Overtime paid now directly affects future obligations to the city's public pension fund, which, as of last July, was $5.2 billion in the red. The fund had only 48 percent of money needed to meet all future obligations, according to an actuarial report released earlier this year.

The troubled pension fund has prompted Mayor Michael Nutter to seek solutions, including using proceeds from the proposed sale of Philadelphia Gas Works to bolster the fund.

The unfunded pension obligations weigh heavily on Philadelphia's budget because they limit the cash-strapped city's ability to spend in other areas, from public safety to education to libraries and other community services.

Thousands of city employees will eventually collect pensions bolstered by overtime. That's because each union contract since the late 1960s has allowed all municipal employees, except police and firefighters, to include overtime earnings in their pension compensation calculation.

Pensions for non-public safety personnel are determined based on the average of an employee's three highest years' earnings, including overtime pay.

For the correctional officer Baylor, his three highest base salaries over the past five years average out to $41,132. That would result in a $21,389 per year pension, if he worked for the city for 25 years.

Factoring in overtime, Baylor's average salary rises to $115,072, boosting his pension to $59,838 – nearly $20,000 a year more than his current base salary.

The difference for Baylor's pension over a 20-year retirement: Nearly $769,000, due to overtime.

Baylor's pension could be greater if his total salary was higher in years prior to 2009. It could also rise if Baylor's total earnings increase in future years.

'The impact multiplies dramatically'

Spiking pensions via overtime is a practice some have called for ending. In a February report, state Auditor General Eugene DePasquale said including overtime earnings in pension calculations is one factor contributing to municipalities' distressed pension plans and recommended excluding such earnings when determining pension benefits.

Including overtime income "can have a significant impact on the pension plan considering that pension benefits can be paid for 20 or 30 years or more," the report said. "And when this spiking occurs for many participants in a pension plan, the impact multiplies dramatically."

Indeed, a 2013 Pew Charitable Trusts report on U.S. cities' shortfall in funding pensions noted that pension spiking has more cities tightening how final average salary is calculated "because they can have a surprisingly large effect on the size of the pension."

Rhynhart, the budget director since 2010, said she was not aware of any studies to analyze the effect of overtime on the city's underwater pension fund — though she noted that she does not sit on the Pension Board.

Francis Bielli, executive director of the city's Pension Board, which has direct authority over the $4.5 billion fund, told Philly.com it is not provided overtime figures. He said they simply use compensation figures from the city Finance Department.

Rhynhart said she and other Finance officials meet quarterly with department commissioners to discuss payroll. Overtime spending is "a big topic of discussion" at those meetings, she said.

Still, she couldn't recall any instances where someone raised concerns about the amount of overtime.

"I get a monthly payroll (from department heads), giving them the benefit of the doubt they have vetted it," she said.

Meanwhile, Barkley, the custodian who's more than doubled his pay with overtime in four of the last five years, said he can handle the long hours.

"I'm not going to delve too far into this. That's nothing to me. I worked on the waterfront before this job. I worked on the docks. The work to me is nothing. Some people might not understand that," Barkley said.