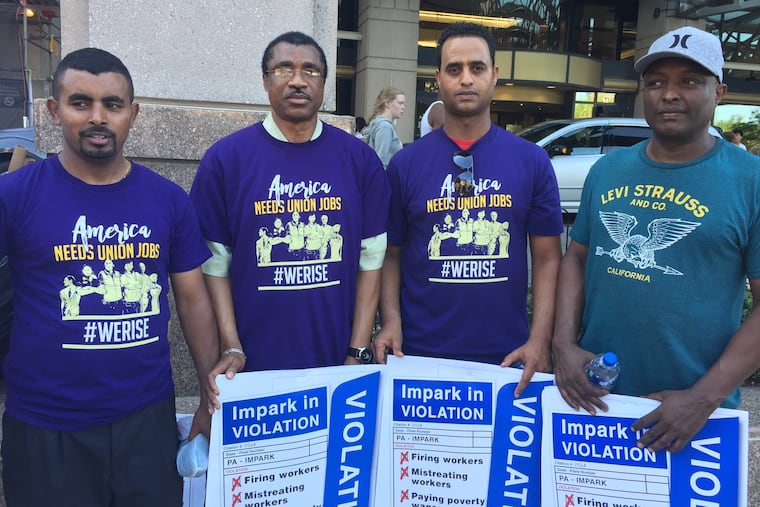

African valets who park the cars at Penn Medicine say they got fired after trying to unionize

Six parking lot attendants, nearly all of them immigrants from Africa, were fired in June by their employer, Impark. Union 32BJ SEIU says it was retaliation for union activity. Impark has denied this.

When he was 24, Surafel Fisiha won the lottery.

His prize wasn't cash, but a visa that allowed him to come to the United States.

He had a good job in his hometown of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia's capital, installing computer networking in universities and banks. But if he lost that job, he knew it'd be hard to find another. And everyone talked about how America was a place of opportunity — maybe, he thought, that meant he'd be able to get a better job and help his family.

America, he soon learned, was far from what he expected. More than a decade later, he again found himself in another unexpected position: as one of the leaders in a campaign to unionize parking lot attendants in Philadelphia.

Now 35 and living in Southwest Philly with his wife, wife's mother, and two toddlers, Fisiha is one of six parking lot attendants who were fired last month for trying to form a union, according to SEIU 32BJ, which is working to organize valets around the city. Their experience offers a window into the challenges private-sector workers face when trying to unionize. The valets who lost their jobs, nearly all immigrants from Africa, worked at parking facilities at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania (HUP) run by parking giant Impark, short for Imperial Parking. Impark spokesperson Leonard Calder said allegations that the company fired employees for union activity are "unfounded," adding that it respects its employees' right to choose whether to join a union.

Fisiha, who goes by "S.F." and worked at Impark for two years before being fired in June, said it was shortly after he encouraged coworkers to sign a union petition that management called him in for a meeting. There, three managers told him he was being fired because he left during the workday to play soccer in May, which Fisiha says is false.

In a memo posted in the workplace, Impark denied firing Fisiha for union activity, saying that he had abused "well-known company policies."

"The important thing," the memo read, "is that Surafel knows what he did and hopefully he will encourage others not to make the same mistake."

His former coworkers, Fatoman Traore, or "F.T.," a Malian immigrant who started with Impark at $4 an hour in the early 2000s, and Thomas Frezgi, a nine-year Impark employee from Eritrea, also were let go.

It's illegal to terminate someone for union activity, but it's a well-documented tactic for employers to intervene with a union campaign, both because it's hard to prove the reason for dismissal and because it sends a powerful message to others. A 2011 report from the left-leaning Economic Policy Institute found that in one-third of union elections, employers responded by firing workers. During 32BJ's years-long campaign to organize Philadelphia airport employees, workers who were especially outspoken about working conditions were fired, incidents which wheelchair attendant and union leader Onetha McKnight said were among the most challenging times during the campaign.

(SEIU has filed a complaint with the National Labor Relations Board about the firings, but this process could take months or years.)

Another common tactic is threatening to stop operations or move labor offshore, and in some cases, like with local news outlets DNAinfo and Gothamist, owners do shut down when workers vote to unionize. In Impark's case, Fisiha and his coworkers say that management told them they'd lose their jobs if they voted for a union because a union would cause Impark to lose its contract with Penn.

Impark, a Canadian company that employs more than 9,000 and operates 3,500 facilities across Canada and the United States, began running the parking lots at HUP and other hospitals in the area in 2001, when it acquired parking operator DLC Management Group. Some U.S. Impark employees are unionized, like those in Seattle, but according to a review of collective bargaining agreements, the company appears to have more union employees in Canada.

Asked how unionization would affect contracts, Penn Medicine Vice President for Public Affairs Patrick Norton said through a spokesperson, "We respect employees' right to organize and have never indicated that any efforts to do so would impact our current contract with Impark/DLC."

If firings and threats to shut down the company are the "stick," the "carrot" can come in the form of raises or promises of change. Before being fired, the attendants said they got an unexpected raise of 17 cents an hour. This bumped Frezgi up to a rate of $10.08, to which Traore quipped, "You're lucky." Traore was making less — $9.48 an hour — after working at the company for six years longer than Frezgi.

But for the valets, like other low-wage workers fighting for unions, it's not just about money. It's about not worrying you'll be fired for any misstep. It's about having a form of representation in a job when every customer complaint — whether it's unrealistic ("You used my whole tank of gas") or insignificant ("Why'd you roll the window down?") or borderline cruel ("You made my car smell bad") — can get you in trouble.

"I work two jobs, I work long hours. That's not the point," Fisiha said. "The point is for respect."

Since coming to the States, he worked at the Marshalls warehouse in the Northeast, at a 7-Eleven, and as a taxi driver, which he says became unsustainable after Uber and the long hours he had to work to afford his weekly $450 medallion payments and household bills. He eventually landed two valet jobs, working back-to-back eight-hour shifts during the week, before he got fired at Impark.

But now he has a house of his own and a family. Though he doesn't have any time to spend with his family or friends like he did back home, he says there's still more opportunity for work in the U.S. than there was in Addis Ababa.

Now he's looking for a second job. And he still believes in improving conditions at parking garages, out of respect for his fellow valets, most of whom are immigrants, like him, from Africa.