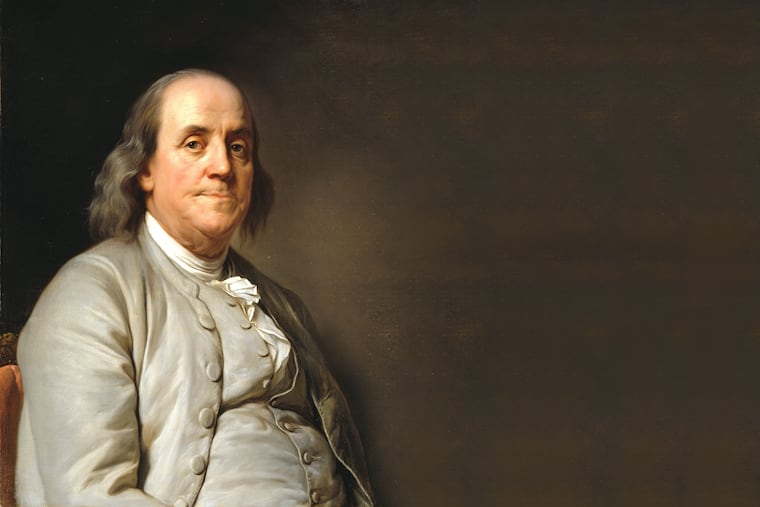

The apology from Benjamin Franklin that predicted the fight over falsehood and hate on social media

In 1731, the polymath addressed the dilemmas of free exchange and the right to offend, in a tract that prefigures today's debates involving figures such as Mark Zuckerberg and Alex Jones.

People want an apology from Facebook for its role in the 2016 election — a real one this time, skeptics say. Just as they wanted one last year from Google for allowing ads to appear alongside offensive videos on YouTube.

But the apology that might best inform the country's anguished debate over free speech and the spread of false information – which found a focal point this week in efforts to limit the platform enjoyed by Alex Jones of Infowars — is the one issued by Benjamin Franklin in 1731. The giant of colonial-era publishing might just be the intellectual lodestar missing from the 21st-century reckoning with "fake news," a term that once meant something, before it was reduced to a rhetorical bludgeon.

"Apology for Printers" was the response of the polymath and founding father to the public outcry over his decision to print an advertisement for a ship sailing to Barbados that seemed to denigrate the clergy. Franklin was no stranger to the condemnation of his readers, he said. He was so familiar with public censure that he had long considered drafting "a standing Apology," which he could republish every time he ruffled someone's feathers. He never got around to it, instead issuing the lone apology to quiet the most recent flap.

Instead of admitting guilt, he rejected the responsibility to regulate the material that he circulated.

"When Truth and Error have fair Play," he wrote, "the former is always an overmatch for the latter."

Franklin's print shop is no analog for the headquarters of the today's technology giants, where algorithms are being tweaked to decide what users see when they move their thumbs around their smartphones. Just as social media sites compete for the time and attention of their patrons, however, Franklin once had to decide how to allocate scarce space in the pages of his newspaper for classified ads, employment notices, lost-and-found records and bulletins about foreign events and far-flung travel. The parallel between the two modes of publishing has been noted on The Junto, a blog about early American history.

It's clear that he learned lessons from this experience, lessons that endure to this day.

The short tract, published on the front page of his Pennsylvania Gazette on June 10, 1731, weighs the civic virtue of free exchange against the social imperative to avoid harm. Franklin upheld the right to offend but urged forbearance, and appeared to have clear standards for material he wouldn't tolerate.

In the guise of apologizing for his "extraordinary Offense," Franklin set out principles of publishing that prefigure some of the arguments made by Mark Zuckerberg, the Facebook chief executive, in his defense of the technology company as a neutral platform, meaning it simply presents the views of others, rather than authenticating them or arbitrating among their competing claims.

Franklin made his first principle the diversity of human opinion, citing an ancient adage, "So many Men, so many Minds." Most of what is printed, he argued, concerns an opinion, by nature subject to disagreement. This fact makes the purveyor of opinion subject to a particular "Unhappiness" not experienced by "the Smith, the Shoemaker, the Carpenter, or the Man of any other Trade," who can do business with people of all viewpoints without offending any of them.

The solution, for publishers, is to allow each opinion equal airing, Franklin wrote – an objective that has grown more complicated as the printed page gives way to the infinite Internet, allowing anyone to self-publish.

Franklin had faith that truth would win out over falsehood, if given a fair chance to compete, and that serving "all Parties" meant being willing to offend. He didn't spell out the terms of fairness, however, and the parties with whom he was dealing were, for the most part, people he knew in the flesh, rather than anyone, anywhere in the world, with a computer and an Internet hookup.

"Being thus continually employ'd in serving all Parties, Printers naturally acquire a vast Unconcernedness as to the right or wrong Opinions contain'd in what they print," Franklin observed. "They print things full of Spleen and Animosity, with the utmost Calmness and Indifference, and without the least Ill-will to the Persons reflected on."

The printer's good intention, he warned, wouldn't stop the offended party from considering "the Printer as much their Enemy as the Author" – a warning lent new meaning by President Donald Trump's attack on the media as the "enemy of the people."

"If all Printers were determin'd not to print any thing till they were sure it would offend no body, there would be very little printed," Franklin wrote.

Yet the ambitious publisher was no absolutist. At the end of his vehement rejection of predetermined notions of truth and decency, point #10 allows for exceptions that find echoes in today's criticism of Jones, who claimed that the 2012 massacre at Sandy Hook Elementary School was a hoax and promoted the conspiracy theory known as "Pizzagate" that led a gunman to open fire in a D.C. restaurant last year.

"Printers do continually discourage the Printing of great Numbers of bad things, and stifle them in the Birth," he wrote.

There were two main cases in which Franklin refused space on his page, he noted: material that "might countenance Vice, or promote Immorality," as well as "such things as might do real Injury to any Person."

Not even "Offers of great Pay" could shake him from this commitment, he affirmed.

Just as giving certain opinions a platform put a target on his back, so, too, withholding one proved controversial.

"In this Manner I have made my self many Enemies, and the constant Fatigue of denying is almost insupportable," he recounted.

Concluding his statement of principles and before moving on to the specifics of the offending advertisement, he quoted the poetry of Edmund Waller, an English orator and lyric poet who sat in the House of Commons in the 17th century.

"Poets loose half the Praise they would have got

"Were it but known what they discreetly blot;"

Franklin then added a final, slightly less mellifluous line of his own: "Yet are censur'd for every bad Line found in their Works with the utmost Severity."

His frustration at the pitch of the debate is fitting for present times. The principles he articulated, with his characteristic irreverence, seem relevant, too.