3 Asian American artists talk labor: The emotional, the invisible, the inconsequential

The Asian Arts Initiative's upcoming 'Working Conditions' examines labor and how it relates to the Asian American experience.

Should people be defined by their work? Should immigrants?

So much of the debate around immigration policy in the United States centers on labor, says Asian Arts Initiative curator Carol Zou: Either immigrants are accused of stealing jobs from "real" Americans, or their contributions to the economy — whether it's how they're building businesses or taking factory work — are used to justify their right to live here.

And that way of thinking about immigration is steeped in tradition: Many early immigrants, like the Chinese or Filipinos, came to the States as laborers.

But those narratives fall short, Zou says. A new exhibit from the Asian Arts Initiative, "Working Conditions," hopes to complicate the conversation. Featuring artists from Hawaii, Toronto, and Philadelphia, the exhibit explores questions of how Asian American lives are shaped by labor conditions and draws attention to the "unrecognized, undocumented, or unseen labor that exists in our society," Zou says.

The exhibit opens Friday and runs until Dec. 15, with performances and poetry readings interspersed throughout.

Here's how some of the featured artists are exploring the way labor intersects with the Asian American experience.

The labor of assimilation

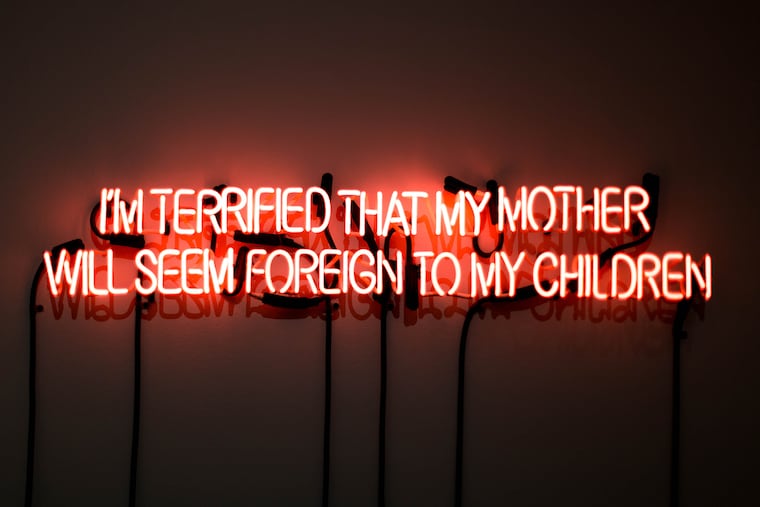

Shellie Zhang's I am Terrified /我担心, a pair of neon signs written in English and Mandarin, refers to what Zhang, a Toronto artist from Beijing, called "the labor behind preserving language and heritage and the labor of assimilation by necessity."

"The piece examines the existential question faced by many non-English-speaking individuals in the diaspora," Zhang, 27, wrote in an email. "They must adapt and learn another language in order to function within contemporary society, most often at the detriment of losing their mother tongue. How do families navigate this change and how does it affect the ways in which they communicate with each other?"

It's also a comment on the "gendered emotional labor that mothers, sisters, aunties, and women carry," she said, as studies have shown it's often women who pass on language to future generations. "I wonder in what capacity women of the diaspora like myself can pass on cultural traditions and language in the U.S. and Canada as the environment becomes more and more hostile."

The labor of community building

When Lisa Pradhan submitted a zine about growing up as a queer Nepali American to the South Asian-focused A1 Bazaar pop-up marketplace, she heard back from a reader who was surprised — and delighted — to discover another queer Nepali American.

"I've never met anyone else who's like you," the reader told Pradhan. And Pradhan, who's based in the Bay Area, could identify: For a long time, she hadn't known anyone who was queer and Nepali, either. It set her on a journey to create In Search of Queer Nepalis, a set of questions that acted as prompts for art pieces she crowdsourced from the Nepali community, including from New York organization Adhikaar.

In Search of Queer Nepalis looks at the "unseen emotional labor it takes to build community," Pradhan, 26, said. She sees the project as a way to lay the foundation for a burgeoning queer Nepali community.

The labor that doesn’t produce anything

Filipino Jewish artist Rebecca Maria Goldschmidt kept hitting dead ends. Goldschmidt, a 31-year-old graduate student at the University of Hawaii who chose that school because she wanted to study the state's rich Filipino culture, tried making suka (Filipino sugar cane vinegar) from sugar canes native to Hawaii. But it didn't work. She tried making paper out of bagasse, leftover cane stock, and after weeks of ripping up the leaves in her studio, crushing them, soaking them, and boiling them, it didn't work, either.

There was nothing that came out of the process that had value, she said. But it made her think about time — about the time it takes to do things, even things that don't turn out, and the labor that we don't see, labor that's easy to forget.

In Hawaii, because of its plantations, Goldschmidt says, there's a lot of talk of labor that's invisible to most people: "We consume and consume and consume but we don't even know the labor that's behind the objects we're eating," she says. Ultimately, her piece about suka, Nabanglo a lamisaan/Aromatic Table, will take the form of a tasting table for sugar cane vinegar. But she hopes it will get participants thinking about the labor behind the food we eat and the relationship between humans and the land.