When past is present: New documentary explores harsh treatment of Chinese immigrants

The topic is not merely an American immigration story, filmmaker Ric Burns said. It's THE American immigration story,

From the working man in the street to the president in the White House, people wanted these foreigners to go, to stop coming to the United States.

They were taking American jobs. And undercutting wages. They couldn't even speak English.

One strategy: Make life hard on those already here, by forcing them to carry special identification papers, and questioning the right of their American-born children to hold American citizenship.

That was 130 years ago. But it might sound familiar today.

It does to Ric Burns, whose new film doesn't explore the Trump administration's crackdown on immigration, but examines the racist government actions against Chinese newcomers at the turn of the last century.

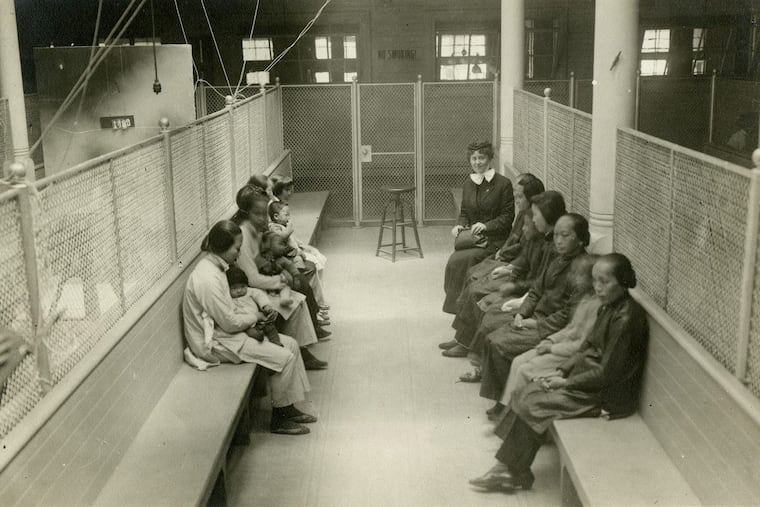

The film, The Chinese Exclusion Act, is a portrait of a largely forgotten, uniquely hateful piece of legislation signed by President Chester A. Arthur on May 6th, 1882. The act singled out one race and nationality, making it illegal for Chinese laborers to enter the United States and banning them from ever becoming American citizens.

"Almost every element of the story reads like a Rorschach of what's going on today," Burns said in an interview. "The language, the posturing and political maneuvering that began in the 1850s, that political maneuvering has not changed in any way."

The documentary, which Burns codirected with filmmaker Li-Shin Yu, debuts nationally at 8 p.m. Tuesday on PBS stations.

The topic is not merely an American immigration story, Burns said. It's the American immigration story, encompassing civil rights and citizenship and what it means to be an American. It shows what can happen when a particular group of people is characterized as a threat.

The 1882 Exclusion Act marked a radical change for a nation that had generally welcomed foreigners. It sprang from a belief among whites, especially in the western United States, that the Chinese were racially substandard — and to blame for unemployment and declining wages.

"I'm the legacy of this system. … It's part of my life," said K. Scott Wong, the Charles R. Keller professor of history at Williams College, who appears in the film.

Wong grew up in Cinnaminson, and his Philadelphia Chinatown roots run deep.

One grandfather, Wong Wah Ding, was known as the "mayor of Chinatown" in the 1940s, quoted and photographed in the newspapers when the press sought an opinion from the Chinese community.

Professor Wong was grown before he learned that his other grandfather was a "paper son," one of scores of Chinese who entered the United States by falsely claiming to be the child of a Chinese-American.

"All those people, they didn't come, 'I want to break the law,'" Wong said. "They were, 'I want to make a living.'"

Chinese began arriving in the United States in greater numbers during the California Gold Rush, in 1849, many traveling from troubled Guangdong Province in the south. All hoped to escape poverty and civil war, and to find their fortune digging on Gam Saan, the Gold Mountain.

Some Chinese successfully dug gold from the earth — earning resentment from white miners. More worked in mining camps and towns, washing laundry and running restaurants, or swinging picks and shovels to build the transcontinental railroad.

Eventually the workforce of the Central Pacific Railroad was 90 percent Chinese.

"Here were cooks, laundrymen, and servants ready and willing," wrote American educator Henry Kittredge Norton. "Just what early California civilization most wanted, these men could and would supply."

The men supplied something else too — scapegoats.

The Chinese were seen as strange, dressed in unfamiliar clothes, their hair woven into a single long braid, known as a queue. When jobs became scarce during the depression of the 1870s, the Chinese became an easy target.

Newspapers took up the cry, with big, front-page headlines that declared, "The Chinese Must Go!"

Anti-Chinese violence swept through the West. Eighteen were killed by a white mob in Los Angeles in 1871, and Chinese homes and businesses were destroyed in Denver in 1880. Five years later the Rock Springs Massacre in Wyoming would leave 28 Chinese miners dead.

That hate was huge, the Chinese population minuscule.

In 1860, the United States had 34,933 Chinese — .001 percent of the population. By 1880, the number of Chinese had tripled to 105,465, but the surging U.S. population meant they still only accounted for .002 percent of the country.

The Exclusion Act had immediate consequences. Wives and children could not come to visit or live. And if Chinese workers traveled home to see their families, they would not be allowed back into the United States.

Ten years later, the Geary Act extended the exclusion law and added an onerous new provision: Every Chinese immigrant had to carry a legal document called a Certificate of Residence, and to present it to authorities when asked. Without that paper, Chinese could face deportation.

Yet more than 100,000 refused to register, demanding that America fulfill the civil-rights promises contained within its founding documents. It was an American-born Chinese, Wong Kim Ark, whose landmark 1898 Supreme Court case confirmed that he and others were U.S. citizens by virtue of their birth on American soil.

Burns has written, directed and produced documentaries since The Civil War, which he produced with his brother, Ken, and cowrote with Geoffrey C. Ward. Co-director Li-Shin Yu has collaborated with Burns for two decades, including the eight-part New York: A Documentary Film.

Burns began work on the new documentary about six years ago, and says the timing of its landing was a surprise, amid the rise of a Trump administration that encourages the view of immigrants as "the other."

"The Chinese were the meta 'other' of the 19th and early 20th century," Burns said, noting that the Exclusion Act and its accompanying bans weren't fully repealed until the 1960s. "They were the 'other' against which an increasingly complex American society could rally itself. … The idea that this couldn't happen, we don't have those kind of racist feelings anymore, I'm sorry, we do have those racist feelings."

TV

The Chinese Exclusion Act

8 p.m., Tuesday, PBS