In Philly's 'last death-penalty case,' killer gets a life sentence instead

Asked whether to impose the death penalty, the jurors, who had already found Robert Lark guilty of the 1979 murder, sent a note: "We are at a deadlock."

On Tuesday, Philadelphia elected a district attorney who has pledged to take the death penalty off the table.

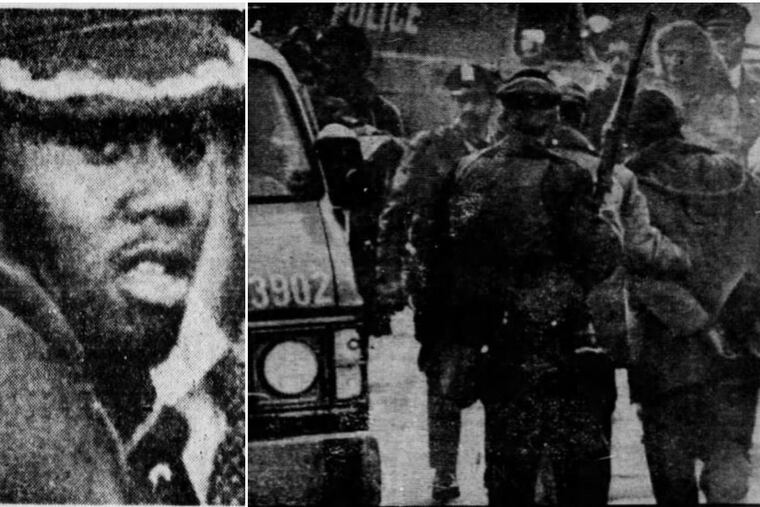

But two days later, prosecutors asked a jury of Philadelphians to impose it one last time — in the case of Robert Lark, a 63-year-old man who has already spent more than three decades on death row for the 1979 murder of 36-year-old Tae Bong Cho at a takeout restaurant Cho owned in North Philadelphia.

The jurors, who had already found Lark guilty of murder, sent a note to Judge Steven Geroff after an hour of deliberations: "We are at a deadlock. Nobody is budging, and there won't be a unanimous decision."

That meant Geroff would have to sentence Lark instead — to the mandatory term of life in prison with no possibility of parole.

"It's obvious to me that you are quite a villain," Geroff told Lark. Then, he tacked 22½ to 45 more years in prison onto the life sentence, for a series of related convictions on charges including terroristic threats and kidnapping.

Lark was first convicted of the crime in 1985. But that verdict was overturned in federal court based on Lark's claim that the prosecutor in his trial had used race-based practices in jury selection. At an evidentiary hearing, the prosecutor could not provide an explanation other than race for striking three African American jurors in the case.

Jury selection for Lark's new trial, which began Oct. 2, took more than a week. In a death-penalty case, lawyers must select a pool of jurors who state they are willing and able to impose the harshest punishment the law provides.

"Each of you," Assistant District Attorney Gail Fairman told the jury, "looked inside of yourselves, and each of you stated, 'Yes, we can do this.'"

A majority of Pennsylvanians no longer support capital punishment, according to a 2015 York College of Pennsylvania poll. One complaint is that so-called death-qualified juries are inherently biased, and studies have shown such juries inherently are more likely to convict.

No one has been executed in Pennsylvania since 1999. Since 2015, Gov. Wolf has maintained a moratorium on executions.

The standard penalty for first-degree murder in Pennsylvania is life in prison, but aggravating factors can trigger the death sentence. The prosecutors described two such factors. The first, they said, was that Lark had murdered a witness. They said he killed Cho on Feb. 22, 1979, because Cho was scheduled to testify in court the next morning that Lark had robbed him at gunpoint two months earlier.

Second, they said, Lark qualified to be executed because of his significant criminal history, which included the gunpoint robberies of a store clerk, of Cho, and of his own landlord.

"The crime was an affront to the justice system," Fairman said.

Lark's lawyers presented mitigating factors: a childhood destroyed by his mother's drug addiction and neglect, and his stepfather's violent abuse.

His birth was a surprise to his 15-year-old mother, defense lawyer Regina Coyne said. "In his first year of school, when he was 5 or 6, he went to five different schools," she said. "He was in survival mode."

She described rats and a leaking roof, vomit on the floor. She spoke of foster homes where he was taken away from his siblings, and described how he ran away from those placements and slept in cars until he could find his siblings and reunite them.

The jury's decision means Lark will move from death row — where for 32 years he has been kept in his cell for 23 hours a day, according to his lawyer — into the general prison population.

Nonetheless, Lark will appeal the verdict, according to his other lawyer, James Berardinelli, who said he had been prevented by the judge from presenting key evidence, including a pattern of questionable behavior by the police who investigated the case.

That, prosecutors noted, means prolonging the pain for Cho's family as well.

Seeing the case return to court, Assistant District Attorney Andrew Notaristefano said, "brought back everything. They thought this was over with, and then they had to relive it all over again."