Federal jury finds Main Line payday lender Hallinan guilty of racketeering conspiracy

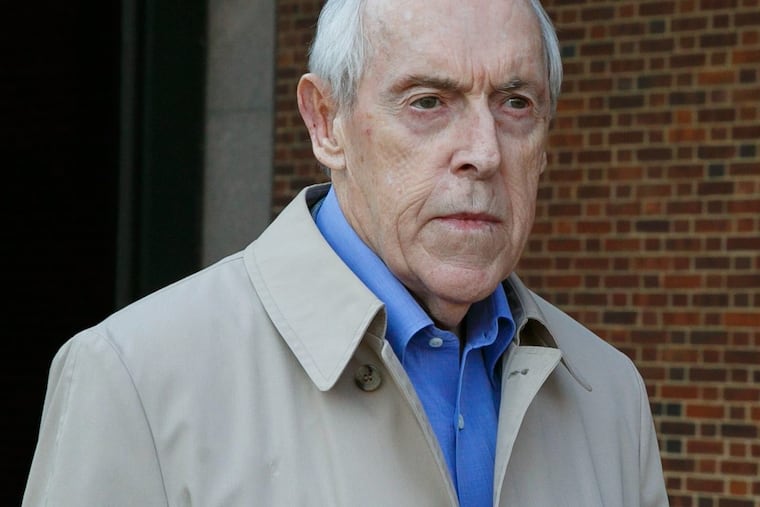

Charles M. Hallinan was known as the "godfather of payday lending"

A former Main Line investment banker known as the "godfather of payday lending" was found guilty of racketeering conspiracy charges Monday by federal jurors, whose verdict cast doubt on the legality of business tactics that have enabled the multibillion-dollar industry for years.

The panel of nine women and three men took less than nine hours to convict Charles M. Hallinan — who in a nearly two-decade career originated strategies that have been widely adopted by other payday lenders — on 17 counts that also included fraud and international money laundering.

Convicted alongside him was his longtime lawyer and co-defendant, Wheeler K. Neff, a man whom prosecutors had accused of helping to devise the faulty legal framework Hallinan used to justify his evasion of state regulations to rake in millions — one low-dollar, high-interest-rate loan at a time.

"Mr. Hallinan has managed to evade justice for more than a decade," Assistant U.S. Attorney Mark Dubnoff said in court after the verdict was announced. "It's time for [him] to start paying the price."

Hallinan, 76, sat stone-faced as the jury forewoman read out one "guilty" verdict after another in the Philadelphia courtroom. The multimillionaire Villanova resident and Wharton grad betrayed little emotion over the fact that he now faces a sentence that could effectively send him to prison for the rest of his life and criminal forfeiture proceedings next month that could strip him of property and assets worth millions.

U.S. District Judge Eduardo Robreno ordered both Hallinan and Neff to remain under house arrest until their sentencing hearings in April. For Hallinan, that means he will spend the next five months confined to his $2.3 million Villanova home.

He is only the latest in a series of payday lenders convicted in recent months of racketeering conspiracy, a crime traditionally prosecuted in cases against Mafia loansharking operations.

Government lawyers in his case and those of other prominent payday lenders — including professional race car driver Scott Tucker, who was convicted last month, and Richard Mosely Sr., found guilty Nov. 15, both by federal juries in Manhattan — asserted that there is little difference between the exorbitant fees charged by money-lending mobsters and the annual interest rates approaching 800 percent that are standard across the payday lending industry.

The cases stemmed from a coordinated effort launched under the Obama administration to crack down on abusive payday lenders who have been accused of preying upon financially vulnerable Americans.

Hallinan's lawyer, Edwin Jacobs, said Monday that his client still maintains that he ran a legitimate and legal business. Christopher Warren, lawyer for Neff, 69, of Wilmington, said he thought he had put on a convincing case that Neff honestly believed he was giving Hallinan sound legal advice.

"We thought our client's good faith had been established beyond belief," he said. "The jury's failure to recognize that is disappointing, to say the least."

More than 12 states, including Pennsylvania, effectively prohibit traditional payday loans through criminal usury laws and statutes that cap annual interest rates, yet the industry remains robust.

Roughly 2.5 million American households take out payday loans each year, fueling profits of more than $40 billion industry-wide, according to government statistics.

Payday lenders say they have helped thousands of cash-strapped consumers, many of whom do not qualify for more traditional lines of credit.

"[Prosecutors] call it predatory lending," Warren said in his closing argument to jurors last week. "A guy who needs $300 fast to get to work probably thinks it's a good thing."

But in Hallinan's case, lawyers on both sides were careful throughout the trial — which began in September — to remind jurors that they were not being asked to render judgment on the morality of payday lending. Instead, they pushed jurors to judge the facts on the specific charges faced by Hallinan and Neff.

Hallinan's conviction is not the first in the industry, but it may be one of the most significant.

"There were hundreds of thousands of victims of Charles Hallinan's lending around the country," said Assistant U.S. Attorney James Petkun, co-counsel to Dubnoff.

As one government witness described him while testifying last month, Hallinan was widely known as "the godfather" of payday lending.

He helped to launch the careers of many of the other lenders who now face possible prison terms alongside him — a list that includes Tucker, a former business partner; and Jenkintown lender Adrian Rubin, who pleaded guilty to racketeering charges in Philadelphia in 2015 and became a key witness against Hallinan and Neff at trial.

Hallinan entered the industry in the 1990s with $120 million after selling a landfill company, offering short-term loans by phone and fax. He quickly built an empire of companies with names like "Tele-Ca$h," "Instant Cash USA," and "Your Fast Payday" that generated nearly $490 million in collections between 2007 and 2013.

But as states started to push back imposing interest rate caps that payday lenders say would have crippled their ability to make money off a customer base with an unusually high rate of default, Neff, a former deputy attorney general in Delaware and a banking executive, helped Hallinan adapt.

Under Neff's guidance, Hallinan developed a lucrative agreement starting in 1997 with County Bank of Delaware, a state in which payday lending remained unrestricted.

Hallinan's companies paid the bank to use its name on loans issued over the internet to borrowers in other states, under a legal theory that because County Bank was federally licensed it could export its interest rates beyond Delaware's borders.

Throughout the trial, prosecutors painted that arrangement as hollow. Hallinan did little more than rent the bank's name to hide the fact that his companies based in a Bala Cynwyd office park handled every aspect of the operation from lending the money to vetting the borrowers and servicing the loans.

"The whole thing was a farce and a sham," said Dubnoff in his closing argument last week.

When a lawsuit brought by then-New York Attorney General Eliot Spitzer effectively ended the "rent-a-bank" program in the mid-2000s, Hallinan and Neff sought similar arrangements with American Indians.

They reasoned that by partnering with federally recognized tribes, which hold sovereign immunity to set their own regulations on reservation lands, they could continue to operate nationwide.

Hallinan paid tribes in Oklahoma, California, and Canada as much as $20,000 a month to use their names to issue loans across state lines.

Prosecutors say the tribes did little beyond housing computer servers that Hallinan sent to them to give their operations a sheen of legitimacy. A representative of one tribe with which Hallinan worked — the Northern California-based Guidiville Band of Pomo Indians of the Guidiville Rancheria — testified that he only later found out that the server he had set up in a shipping container on his reservation was devoid of data and was not even connected to the internet.

When plaintiffs' lawyers and regulators began to investigate these arrangements, Hallinan and Neff engaged in legal gymnastics to hide their own involvement, government witnesses said.

Testifying in a 2010 class action case in Indiana, Hallinan maintained that he sold the company at the heart of that suit to a man named Randall Ginger, the self-proclaimed hereditary chieftain of the Mowachaht/Muchalaht First Nation in British Columbia.

But evidence presented by prosecutors showed that Hallinan had continued to run the operation and pay its legal bills even while he was paying Ginger to claim the company as his own.

Ginger later asserted that he had almost no assets to pay a court judgment, prompting the case's plaintiffs to settle their claims in 2014 for a total of $260,000.

That swindle, prosecutors now say, helped Hallinan escape legal exposure that could have cost him up to $10 million.

Ginger also was charged in the case, but remains a fugitive in Canada. The investigation — led by the FBI, the IRS, and the U.S. Postal Inspection Service — has elicited four other guilty pleas from people tied to Hallinan's businesses.