For this writer, Alabama Senate race summons ghosts of Birmingham church bombing

I dashed into the house to see pictures of four young girls - girls who looked like me - flash across the television screen.

I grew up in Florida. North Florida.

But some of my earliest memories are of Alabama: red-clay roads traveled to visit grandparents; a rickety, wooden bridge that seemed too dangerous to cross even to a child; and the time I dashed into the house to see pictures of four young girls — girls who looked like me — flash across the television screen.

It was Sept. 15, 1963.

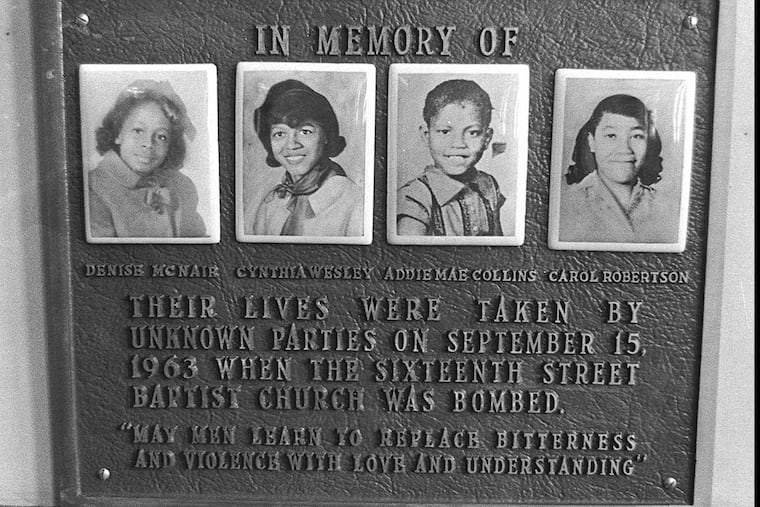

The four girls — Addie Mae Collins, Denise McNair, Carole Robertson and Cynthia Wesley — had been killed in the bombing of Birmingham's 16th Street Baptist Church. Denise was 11, the others 14.

Until that moment, it was possible for a black child living in a segregated South to have no concept of racism. Unless you were taking part in demonstrations in Bull Connor's Birmingham, unless you were in Selma, or in Jackson, or in Philadelphia, Miss., a black child could feel sheltered and safe in countless small Southern towns where there was little "agitation."

But suddenly, looking at the girls' faces, I understood what it meant to be black in America. I was 9, and I realized I could be killed for going to church.

Now, decades later, Alabama's controversial U.S. Senate race has summoned the ghosts of Birmingham's past.

Accusations that Roy Moore, the Republican candidate, molested a 14-year-old girl has put him and his Democratic opponent, former U.S. Attorney Doug Jones, in the national spotlight.

And Jones is best known for prosecuting the last two surviving Ku Klux Klansmen long suspected in the church bombing.

Seeing news of that case again, I was carried back to the bombing and my own pilgrimage to Birmingham 30 years afterward.

"People are trapped in history and history is trapped in them," James Baldwin once wrote.

Despite FBI evidence collected by 1965 showing that at least four men — Robert "Dynamite Bob" Chambliss," Thomas E. Blanton Jr., Bobby Frank Cherry, and Herman Cash — had bombed the church, then-FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover refused to arrest them, testimony from the trials Jones prosecuted revealed.

It would eventually take nearly 40 years for some semblance of justice.

Chambliss was the first to be tried and convicted in 1977. Later, Jones prosecuted Blanton in 2001, and Cherry in 2002. Both were convicted and sentenced to life in prison; Cherry died in 2004. Cash had died in 1994 without being charged, and Blanton was denied parole last August.

But years before these men ever saw their day in court, somehow, we who were children at the time of the girls' death understood that a nation's grief would bring change to America. Others my age — Oprah Winfrey, Denzel Washington, Condoleezza Rice — were told by parents, teachers, and the little old ladies at church to make sure to "get your education." There would be no celebrating Christmas that year, as many black families were protesting the violence, but still, there was hope. Our parents knew that doors would be opening for us that had not been opened to them.

A year after the bombing, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was passed, followed by the Voting Rights Act of 1965. (We had no idea then those advances would be followed by policies leading to mass incarceration and the school-to-prison pipeline.)

Young people knew "this was our moment," said Kariamu Welsh, a professor of dance at Temple University. Black people were about to help shape change in the country.

Welsh was about 13 and living in Brooklyn in 1963. She said the memory of the girls "still haunts me.

"I think of them in those pictures and they were just waiting to live their lives."

I, too, remained haunted by what could have been, and in 1993, on the 30th anniversary of the church bombing, I traveled to Birmingham.

The editors at my newspaper denied my request to cover a week of events commemorating the girls. (Interestingly, newspapers weren't covering issues about race and gender then; now we have a team of reporters covering identity, and I am one of them.) So, I took vacation time and went to Birmingham, anyway.

I made my way to the church; to Kelly Ingram Park where statues depicted children being threatened by police dogs; to the Civil Rights Institute; and to the cemetery where three of the girls were buried.

Then I found myself at the front door of Alpha Robertson, the mother of bomb-victim Carole.

It was a sunny September afternoon, and I paused as I stood on her wide front porch, listening to the Parker High School Band practicing at the school nearby.

I didn't know then that Carole had played the clarinet and was supposed to join the band the Monday after she was killed. I only wondered if living near the high school had been a constant source of sadness for her mother.

Mrs. Robertson, a retired school librarian, was gracious and kind, even though she declined to give me an official interview. (I discovered that many of the girls' relatives were soured about reporters coming to town.) Still, Mrs. Robertson invited me inside and offered me a cold soda.

Something besides journalism had propelled me to her front door, I told her. Something about the debt one generation owes another for its sacrifices.

I told her if she didn't want to talk to me, then perhaps I could talk to her, about how I had never forgotten her daughter and the other girls.

I told her I had grown up with two friends I met in our 4th grade class the year of the bombing and that we had remained friends throughout our lives.

As we graduated high school, began college, careers, marriages and families, I sometimes thought of what lives the four girls might have lived.

Mrs. Robertson took my business card, and I was surprised and flattered a few months later when she sent me a Christmas card. We stayed in touch sporadically over the years, and I continued to keep a file about the case.

After Blanton's conviction in 2001, she had been quoted in the New York Times: "I'm very happy that justice came down today, and, you know, that's enough, isn't it? You know, I didn't know if it would come in my lifetime." She was then 82.

Mrs. Robertson once told me how she refused to hate all people because of what a few white men had done.

"You can't waste your life hating," she said.

I had not known she had suffered from cancer and strokes. Then in August 2002, I saw a news report that she had died at age 83.

It made me reach out to Jeff Wallace, the district attorney's representative for the team Jones led.

"She was one of those people that you warm up to, just in the way she talks," he told me. "The honesty's out there on her sleeve, the sincerity is on her face."

Jones offered a similar take in her New York Times obituary: "We referred to her as the moral center of the universe. She just had that presence and aura that brought you in and cradled you."

On the morning of Sept. 15, 1993, church bells rang across Birmingham at 10:22. The anniversary program was to take place at the 16th Street Baptist Church. When I got there, I saw that someone had placed a single yellow rose on the front steps.