At Penn State, slaying still haunts

As a State College murder mystery nears its 40th anniversary, interest in finding the killer is strong. Leads are few, but police say the case remains open.

On the chilly Friday after Thanksgiving, 1969, a killing took place in Penn State's largest library that has baffled investigators and fascinated amateur sleuths ever since.

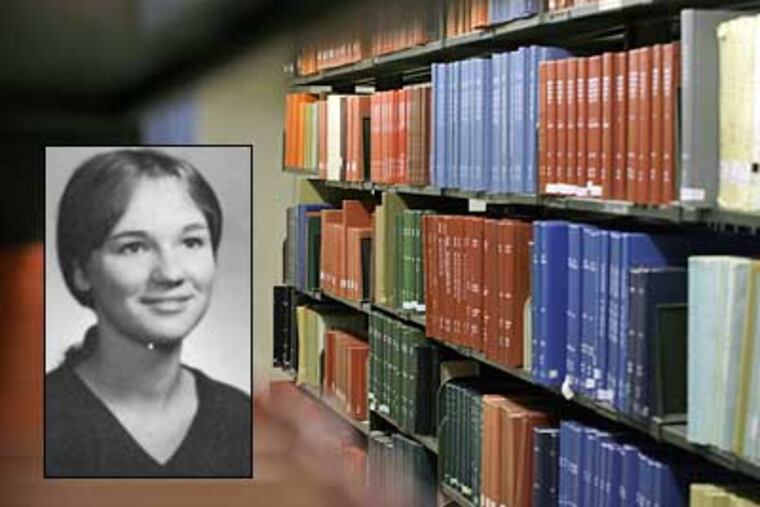

A graduate student, 22-year-old Betsy Aardsma, was stabbed once amid the creaky shelves of Pattee Library. She bled to death from the chest wound.

Though a man was spotted hurrying out of the library, no one was ever caught. A state police investigation is nearing the 40-year mark without an arrest or a named suspect.

Students to this day still whisper about the unsolved slaying.

"One of my friends won't come down here because of it," said Roberta Chapman, studying this month in the library's basement, a few yards from where Aardsma was killed between bookshelves.

The slain woman was from Michigan, was in a stable, long-term relationship, and had a clean personal history, a combination that for a decade has kept investigators grappling for a motive for her death. Speculation that she was killed for interrupting a drug deal or another covert rendezvous never led anywhere.

Nearly four decades later, state police are still actively working the case, and they have begun to solicit tips from a handful of amateur investigators fascinated by the mysterious stabbing.

A Web site, built by a man who sells furnaces, dangles a $2,000 reward for leads. A Penn State lecturer born years after Aardsma died doggedly pursues new information on the case and publishes what he comes up with in the university's alumni magazine. A retired Wall Street professional and Penn State alum throws himself into the case as a sort of unpaid second career, consulting retired police for investigating tips and interviewing scores of people who were around Aardsma or the investigation.

None of them knew or is related to Aardsma, but each has gone far to investigate her death. One even sought advice from a former assistant director of the FBI, Neil Welch.

"Betsy reminds me of my sister, who went to Penn State," said Derek Sherwood, who set up the Web site whokilledbetsy.com and heard about the killing while growing up near State College. "She told me she was terrified of the stacks [and said], 'I never went there unless I had to.' "

He was born about 10 years after Aardsma's murder and is among many too young to remember the killing yet intrigued by it.

"There's still a good deal of mythology on campus about the murder," said Penn State English professor Nicholas Joukovsky, who spoke with Aardsma in his office minutes before she was killed. "I mean, this is something that, undergraduates today, many of them are still aware of the girl who was murdered in the stacks.

"They don't associate a name with the case, but it's part of Penn State lore and has been ever since the time of the killing."

The ongoing interest has caught the attention of state police, who still regard the case as open. Investigators have talked to several of the amateur sleuths about their findings and are planning DNA testing and other evidence reexamination, state police said.

"You'd think it was a cold case, but it's not that cold," said Capt. Jeffrey Watson. "We're moving forward." But he would not say in which direction.

'She had a lot of work'

When it happened, the shocking killing at a big university on a small-town campus made news beyond Pennsylvania's borders as police grasped for the trail of the killer.

Aardsma was pretty, good-humored, and a hard worker, her friends said. She had traveled back to State College on Thanksgiving in 1969 after a dinner in Hershey with her medical-student boyfriend and a group of his friends.

They were on the verge of getting engaged, but each had studies to pursue at schools 100 miles apart. So they decided to part, with Betsy taking the bus back to State College.

"I always regret it," said David Wright, who had been dating Aardsma since they were college juniors in Ann Arbor, Mich.

He said Betsy never mentioned feeling threatened, but he believed her killer had pursued her. In the days after the killing, he was interrogated repeatedly and rethought, again and again, how they could have made different choices.

That she could have prevented it by not returning to State College was a difficult notion for Wright to drop.

"It probably would have happened anyway," he said, "but I was going into finals after Thanksgiving, and she had a lot of work to do. She always came down by bus, and instead of staying over that Thursday night, she went back."

Wright is now a doctor in the suburbs of Chicago. He and his wife of 35 years have four children.

Back in 1969, the news his then-girlfriend had been mysteriously slain in the library reached him at the end of a group study session. Aardsma hadn't said anything to him - or written anything in her daily letters - that indicated the slightest premonition of danger.

Lots of work to do

Then, as now, the bucolic campus managed to remain relatively isolated from society's problems. Serious crimes were rare enough that campus police were mainly security guards.

On the Friday afternoon she was killed, Aardsma had made a 10-minute walk from her dorm to visit the offices of Joukovsky and another professor about her progress on a paper about research methods before going into the library's dim book stacks.

Due to a solid work ethic, Joukovsky said, she had been "one of the better students in what was a very challenging course" he co-taught on British and American literature. She told Joukovsky she would bring him a library book she had used in earlier work for the 60-student class.

"This was a really incredibly demanding course back then," Joukovsky said.

During that era, graduate English students routinely remained on campus that holiday week, recalled journalist Linda Marsa, a close friend of Aardsma's.

She said Aardsma was a bright, friendly woman contemplating how her dreams fit into what she called "the keys to the Country Squire" lifestyle of a doctor's wife.

"We were so earnest," said Marsa by phone from California. "Everybody had stuck around to do these reports."

Pattee Library did not have today's fluorescent lights, computer kiosks, or central air-conditioning, but the low-ceiling stacks are otherwise much the same as in Aardsma's day. There are floor-to-ceiling dark-green bookshelves and, despite the air-conditioning, there are still open grates between each floor for air circulation. When people are scarce, footsteps echo.

Aardsma was in a narrow row of shelves that now houses bound foreign-language periodicals when she was set upon, according to the locations given in police reports.

She was stabbed once in the chest and grabbed a shelf, sending a row of books cascading down. Some students overheard the noise and found Aardsma on the floor.

They tried to help and initially thought she had fainted. She was wearing a red sweater and red dress on which blood did not show, but she bled into her lungs and died in the library.

Her last letter to Wright arrived the next day. Like the others, it did not mention concerns about her safety, he said.

Digging into the case

Various accounts have one, or two, suspicious characters wandering around the stacks at about the time it happened. One student told police he followed a man walking quickly out of the library. However, state police came up empty while speculation swirled, never finding the killer or even the knife the killer used. Some characters were questioned and released, but no suspect was ever publicly identified, no arrest ever made.

As with most high-profile crimes, there was an initial wave of tipsters and theorists that trailed off, State Police Capt. Jeffrey Watson said.

But the mystery lingered.

In the 1980s, a writer named Pamela Kraske delved into the case with help from then-Centre County District Attorney Ray Gricar. She initially thought the mystery could be a true-crime book, but ended up using the findings as a basis for a science-fiction tale involving time travel.

"I did a lot of research and was like, 'There's no way I could write a nonfiction book,' " said Kraske, who published her novel, 20/20 Vision, as Pamela West. "I didn't want to be sued. I didn't have any evidence, and I wasn't going to name anybody, so I turned it into a fiction novel."

(Gricar disappeared in 2005 and has not been found. The investigation has included combing Kraske's novel for clues, because elements of his disappearance are similar to the book's events.)

Others dug into the case and decided to try to solve it.

On whokilledbetsy.com, Sherwood collaborates with Penn State English lecturer Sascha Skucek, who has written several State College Magazine articles about the slaying, to collect findings. The site has many old news clippings, new analyses of evidence, and other notes about the case each has collected.

"We're basically trying to re-create the police file," Sherwood said. "If they won't let us see it, we'll make our own."

On a recent walking tour of Aardsma's final hours, from her dormitory to the library, Skucek ran down the theories about her death - with supposed culprits ranging from a professor who died mysteriously a month later to people interrupted during a covert meeting for drugs or sex - and their flaws. Ducking under the low light fixtures to detail Aardsma's movements in the stacks, Skucek said the stabbing was no crime of genius.

"Another 30 seconds each way and he'd be caught," Skucek said of the killer. "It's a case of complete luck."

'Loss of innocence'

He and Sherwood have their theories about the case, but are still looking to speak with people who were around the library, such as the student who told police he followed a man who hurried away.

Another civilian who has dug into the case in recent years, retired Wall Street consultant and aspiring writer Bill Earley, tried to find the same former student. Earley learned that the man had died - a common problem for the civilians researching Aardsma's murder.

"People moved. They died. They went away," Earley said.

Earley enrolled as a graduate English student at Penn State shortly after Aardsma's death and had heard about the murder on the radio. It jarred his idyllic concept of Happy Valley, and it stuck with him.

"It really was the classic loss of innocence," Earley said.

Decades later, with his finance career winding down, he began looking into the case and asking law enforcement figures how to investigate it.

"It's obviously consumed a hell of a lot of his time and energy in the last few years," Welch, the former assistant director of the FBI, said of Earley, who had sought his advice. "I can see how something like this would grab a hold of you and get you on a pursuit like Don Quixote."

Earley assembled his findings in manuscript form, for a book that he says is unfinished and that he has no plans to publish. In it, he names a person he suspects to be the killer, a different person from the one Sherwood suspects. He is hopeful about the ongoing police effort.

"These guys spent a lot of money and a lot of hours on this," Earley said.

'Renewed interest'

Trooper Kent Bernier inherited the Aardsma case with another state police trooper two years ago, after the previous investigators retired. Bernier said he checked whokilledbetsy.com regularly and had been in touch with Sherwood, Earley, Skucek and others.

"We're just looking at it differently and trying to do different things that haven't been done yet," Bernier said.

Their search for new angles on the old slaying includes modern forensics testing unavailable to the 1969 investigators.

"It's possible now that DNA might be a big breakthrough for us," said Bernier.

He would not give specifics on what was to be tested.

Whether the police investigation comes to a prosecutable case will fall to Centre County District Attorney Michael T. Madeira to decide. He said he was far from having enough of a case to take to a grand jury, though state police had displayed what he called a "renewed interest" in solving the case.

"There is significant value to that," Madeira said, "but it is not the same as having evidence."

Talk of the unsolved killing still resonates around State College, where the library stacks remain a place nonstudents can freely enter and wander.

Old newspaper clippings and other messages appeared where Aardsma was slain to mark the killing's 25th and 30th anniversaries. They could have been the work of the killer or a macabre prank. Other unexpected things have happened as new generations of students learned of the slaying.

A Facebook.com account for "Betsy Aardsma" exists, with a shadowy profile picture attached. Currently, all 15 accounts linked to it as "friends" were those of Penn State students or alumni who had graduated within the last two years.

Aardsma's family still lives in Holland, Mich., and has been contacted from time to time by people interested in the case, including Skucek and Earley.

Carole Aardsma, Betsy's sister, said the family retained a faint hope that investigators would get somewhere, though the interest in it was difficult to deal with.

"Honestly, we have mixed emotions, because it dredges up a lot of bad memories, too," she said. "We have nothing against what they're doing. We hope it leads somewhere."

View a short film, "Murder in the Stacks," which examines the legends growing out of the Betsy Aardsma case, via http://go.philly.com/unsolved.

The film was made in 2003 by Penn State student David Milone.

EndText