Stan Hochman: Raised fists felt round the world

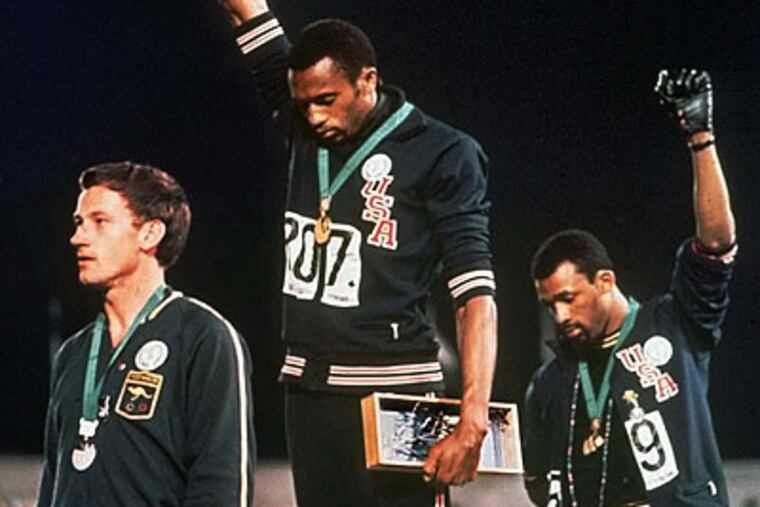

SILENT GESTURE, that's what Tommie Smith had in mind when his wife bought the black gloves in Mexico City. Then he won the 200-meter race at the 1968 Olympics and he slithered his hand into the right glove and handed the left glove to John Carlos, who had finished third.

SILENT GESTURE, that's what Tommie Smith had in mind when his wife bought the black gloves in Mexico City. Then he won the 200-meter race at the 1968 Olympics and he slithered his hand into the right glove and handed the left glove to John Carlos, who had finished third.

Silent gesture, indeed. No punches thrown, no bullets fired, no blood shed. Kaboom! Only trigger-quick punishment and the mushroom cloud of controversy and bitterness and anger that hovers to this day.

Two black athletes on the victory stand, shoeless, a clenched fist thrust into the Mexico City dusk, heads down while the anthem played. Prayer? Or defiance? The crowd gasped and the media mumbled and the Olympic brass growled in the 63 seconds it took to get to "land of the free and the home of the brave."

Forty years later and Carlos insists that the demonstration was his idea, not Smith's. Still insists that he intentionally slowed in the final 50 meters to allow Smith to win the race, creating a gash, a salt-rubbed wound that time cannot heal.

They snipe at each other, in interviews, in books. Perhaps they were unprepared for what happened to them. The instant response: tossed from the U.S. team, given 48 hours to leave the Olympic Village, sent home in shame. Unprepared for the bleak years that followed, the difficulty finding a satisfying job, the suicide of Carlos' wife.

Unprepared too, decades later, for changing times and changing moods, for the honorary degrees awarded them by San Jose State. And then, in 2005, for the 20-foot-high sculpture that the school erected depicting that memorable moment on the victory stand.

There's a fuzzy parallel to Muhammad Ali here. Ali refused to step forward in 1967 at the Houston induction center (his own rare silent gesture) and all hell broke loose. He was stripped of his boxing license before you could say Jack Johnson, forced into almost four years of boxing exile.

Smith and Carlos belonged to the Olympic Project for Human Rights. And one of their goals was to restore Ali's license to fight. Ali went from hated to beloved and ultimately was chosen to light the Olympic flame at the Atlanta games.

It has not played out that way for Smith and Carlos. They thought that they had chosen the right place and the right time to protest. They failed to realize the power of the folks who looked on an Olympic victory stand as sacred ground. And, maybe, they weren't eloquent enough to convince the media that their cause was righteous, and what better place for an athlete than the Olympic victory stand?

I was there and this is what I remember: I remember Carlos in front on the turn, then fading, nipped for second by Australia's Peter Norman. I remember Smith leaning into the tape, setting a world's record of 19.83 seconds, a record that would last 11 years.

I remember the slow procession to the victory stand. The pace of condemned men going to the gallows? Or the wary gait, chins down, of dedicated men finding their way through a lethal minefield to a place in history?

I recall the baffled media trying to make sense of the black-gloved fists, the black scarf around Smith's neck, the black socks, no shoes. I recall a British journalist turning to me and saying, "You don't wear your Sunday best when you go out to fight for truth and justice."

And I said, "Ibsen . . . 'Enemy of the People,' " because it was close enough to one of my favorite lines from one of my favorite plays, and the British guy grinned like we'd won something on "Jeopardy."

We waited for what seemed like an hour before they brought Smith into the interview room. A Greek sportswriter wearing one of those starched, white, pleated shirts breathlessly asked the first question.

"Mr. Smith," he stammered, "who is the coach most responsible for your running style?"

Reaction was swift, violent. Paul Zimmerman, a burly New York Post writer, bear-hugged the guy and tossed him aside. And then started the torrent of questions about the protest.

The answers are a blur, but I remember Smith saying that it had nothing to do with Black Power or the Black Panthers, that an Olympic boycott by black athletes had been discussed and rejected, that it was all about human rights not civil rights, that Norman had willingly agreed to wear an Olympic Project for Human Rights button on the stand.

No one has ever pinned down the symbolism. Lee Evans, another outspoken runner, suggested that Smith wore the glove because he did not want to shake Avery Brundage's hand. Brundage, referred to as Slavery Avery by some athletes, was the rigid USOC leader who welcomed certain African nations to the Olympics despite their apartheid policies.

Brundage did not present those medals. The black socks apparently represented poverty, the clenched fists unity, the beaded necklace a protest against lynching.

The noisy debate didn't end there. Several days later, George Foreman won the heavyweight title and waved two tiny American flags in the ring in some kind of ill-conceived counterpoint to what Smith and Carlos had done.

What Smith and Carlos did played out against a turbulent year in America, the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., race riots in major cities. Americans flinched when race and sports and politics careened into a three-way intersection without traffic lights.

The moment remains, shrouded in mystery, still controversial after all these years. *