The worst ever: The 1972-73 Sixers

The help-wanted ad that ran sporadically in The Inquirer during the spring of 1972 was in retrospect an organization's cry for help.

The help-wanted ad that ran sporadically in The Inquirer during the spring of 1972 was in retrospect an organization's cry for help.

The 76ers, without a coach since Jack Ramsay's prescient postseason departure for Buffalo, without any willing candidates to replace him, and without any hopes for success, decided to turn to the classifieds, as if the team were seeking another accountant or a ball boy.

It was, even in that simpler NBA era, a sign of desperation and one that foretold what would turn out to be the worst season in league history.

As everyone knows, those 1972-73 76ers were 9-73, a record for futility no team had seriously threatened until this season's New Jersey Nets, who are 7-59 and will play the 76ers tomorrow night at the Wachovia Center.

If the Nets fail to win three of their final 16 games, the dissections will begin. They will endure until some team, unlikely as it is to fathom, is even worse.

Meanwhile, 37 years later, the reasons for the 76ers' historic hardwood hardships seem clear: Wilt Chamberlain's desire to get back to the West Coast, bad trades, and a series of horrendous drafts.

Still, much of the blame clings to their coach, Roy Rubin, the virtually unknown New Yorker whose sad-sack countenance remains the public face of this city's worst sporting disaster.

That story began when Jules Love, who was a stockbroker, a former basketball star at John Bartram High School, and a friend of Sixers owner Irv Kosloff, saw The Inquirer's ad and thought immediately of an old buddy, Rubin.

Love telephoned 76ers general manager Don DeJardin to make his pitch. A longtime coach at Christopher Columbus High School in New York and one of the Five Star Basketball Camp founders, Rubin had just completed his 11th year as Long Island University's modestly successful coach.

"I said to the GM, 'I've got a candidate,' " Love, now 78 and retired in New York City, said. "Then I told him about Roy. And he said, 'You mean he's interested in us?' "

When Love called Rubin to tell him what he'd done, his friend's response was, "You [SOB]!"

Rubin got an interview and, in part because Marquette's Al McGuire and a dozen others had turned it down, the job.

On June 15, just two days before the Watergate break-in would create an even bigger mess in Washington, the little-known 46-year-old was introduced to a bewildered Philadelphia.

"He isn't exactly a household name," Kosloff, who died in 1995, explained at the time. "He's no Al McGuire. Or any McGuire for that matter."

A team desperate enough to run a help-wanted ad also was desperate enough to lock up Rubin, signing him to a three-year, $300,000 deal.

The $100,000-a-year salary was astonishing given his lack of NBA experience and the fact that Chamberlain, about to start the final year of arguably the greatest NBA career ever, was earning just $200,000 with the Los Angeles Lakers.

Rubin, it quickly turned out, had no idea how to coach NBA players. The 76ers started with 15 straight defeats. As grumbling in the locker room and beyond increased, Jack Kiser, the Daily News' beat writer, began referring to him daily as "Poor Roy Rubin."

"The face was Phil Foster," Inquirer columnist Frank Dolson wrote. "The voice was Rodney Dangerfield. The paunch was Jackie Gleason. The mission was impossible."

In defense of his friend, and perhaps feeling guilty for what his calls had wrought, Love began to bring a megaphone to games at the Spectrum.

"I'd turn it toward the press box and yell at Kiser and the others, 'Lay off Roy Rubin! Give him a chance!' " Love said.

But it soon became apparent that Rubin didn't deserve much of a chance. He benched his one familiar star, 36-year-old Hal Greer; quickly alienated the rest of the team; and seemed either unwilling or unable to change.

On Jan. 23, after months of speculation, he was fired. The 76ers were 4-47.

His hiring, especially in light of how things turned out, seems no less incomprehensible now.

"During halftime," recalled Dale Schlueter, a 76ers center then, "he'd say something like, 'Way to go, guys.' Then he'd turn to his assistant and say, 'OK, how many minutes we got left until the second half starts?'

"He was completely lost."

In fairness, it was not all Rubin's fault.

The enigmatic Chamberlain had forced a trade to Los Angeles in 1968. Luke Jackson retired prematurely with injuries. Ramsay, also the general manager between 1966 and 1971, and DeJardin were lousy talent evaluators, drafting a succession of stiffs and trading away Chet Walker, Wali Jones, and others.

From 1967 to 1971, the Sixers had an unparalleled run of horrible No. 1 picks - in order, Craig Raymond, Shaler Halimon, Bud Ogden, Al Henry, and Dana Lewis. All were monumental busts, and by 1972-73, all were gone.

The picks were so surprising, they often stunned those selected. After the 1970 draft, when a sportswriter telephoned Henry to ask how it felt to be the 12th pick in the first round, the Wisconsin product sounded puzzled.

"Don't you mean the first pick in the 12th round?" he asked.

The year before, Ramsay's final team had gone 30-52. But its star, Billy Cunningham, soon jumped to the American Basketball Association, and Ramsay wisely shuffled off to Buffalo. The future was bleak.

Kosloff knew he needed a name to maintain interest in his fading club. He tried for McGuire, but the gregarious Marquette coach wanted too much. When several others turned him down, the owner lowered his standards.

That led to the newspaper ad and, eventually, Rubin.

The New Yorker appeared to have some sense of what awaited him. At his introductory news conference, he acknowledged that he was entering a difficult situation.

"Who knows?" he mused. "Maybe two weeks after the season starts, I'll feel like killing myself."

The Sixers would be 0-7 by then. Rubin hadn't killed himself, though already many of his disgruntled players might have suggested it.

In one of his first acts, and one certain to alienate almost everyone, Rubin relegated Greer, the lone familiar face and a popular all-star, to the end of his bench.

"I felt so sorry for Hal," said Schlueter, who arrived in an early-season trade for Dave Wohl. "He should have been a starter or at least a backup. But he never even got an opportunity to play. That wasn't right."

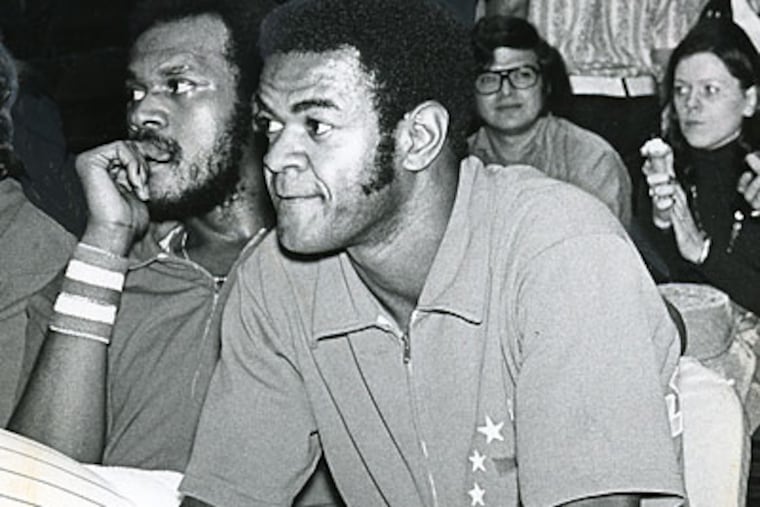

Players such as Fred Carter (named the team's most valuable player), Leroy Ellis, Tom Van Arsdale, and Kevin Loughery kept the Sixers in many games. But neither they nor their coach had answers in crunch time.

On the court, the Sixers lacked a legitimate center, had no go-to guy on offense, and played with little cohesion. Off the court, with Greer nearly invisible, they lacked a leader. It didn't take long for Rubin to become a focus of everyone's discontent.

"Roy told me that the guys just didn't want to play," said Love, the former Bartram star and owner's friend.

Players came and went regularly, 19 in all that year. The losing had to be particularly tough for two - Ellis and John Q. Trapp. A season before, they had played for the Lakers, who won a record total of 69 games.

Whatever his coaching deficiencies, Rubin was a nice man and the job was tearing him up. He lost 40 pounds and plenty of sleep in addition to all those games. Eventually, he even found it difficult to drive to the arena or talk with reporters. Not surprisingly, in the face of so much public criticism, he got defensive.

"Why can't someone else take some of the blame?" he said. "I'm not the one who misses the shots, who throws the ball away, who won't box out. They're killing me. They're trying to take my livelihood away from me."

Rubin impressed no one. Even Harvey Pollack, a loyal and longtime 76ers employee, called him "a bad coach." After a .500 preseason, when the Sixers opened 0-15, he appeared to give up on players who he would say gave up on him.

The Sixers finally won, at Houston, on Nov. 11. By then, some Philadelphia newspapers had stopped traveling with them. But Rubin wanted to make sure the fans learned of his first NBA win. So late that night, he telephoned a sleeping Dolson, who recounted the conversation in his 1981 book, The Philadelphia Story: A City of Winners.

"Is this you, Frank?"

"Uh, yes. Who's this?"

"This is Roy."

"Roy who?"

"Roy Rubin [pause]. Of the 76ers. . . . We beat the Houston Rockets. . . . I figured you'd probably have some questions you'd want to ask me. So go ahead. Shoot."

"Well, there is one thing."

"Yeah, yeah, what's that?"

"Do you have any idea what time it is?"

The Sixers would follow that victory with six more defeats. They would beat the Buffalo Braves on Nov. 28 but wouldn't win a home game until Dec. 6, against the Kansas City-Omaha Kings.

The Sixers' already ailing attendance took a turn for the worse, plummeting by nearly 3,000 a game to an average of 5,901.

Such consistent losing was a lot easier then than it has been since, said Carter, since there were just 17 teams, not 30.

"With the way the talent is spread so thin throughout the league now, no matter how bad you are, you're going to run into a team that you can beat from time to time," Carter said. "That wasn't the case with us."

Even teams the '72-'73 Sixers might have been expected to beat - Buffalo, the Portland Trail Blazers, and Cleveland Cavaliers - wouldn't allow it. While those three teams were a combined 74-172 that season, Philadelphia was 2-16 against them.

"Once the losing got really bad, nobody wanted to lose to us," Schlueter said. "You could see teams playing with more energy because of that. I even think that the refs got caught up in that sometimes."

Fourteen more losses followed the Kings win before Rubin got the last victory of his coaching career on Jan. 7, at Seattle. At the all-star break, after nine consecutive defeats left the Sixers at 4-47, Kosloff fired Rubin.

Loughery was named coach, and the much-relieved Sixers responded by losing 14 straight games. But they showed mild improvement, winning five of seven in February before dropping their final 13.

Incredibly, when Loughery jumped to the ABA's Nets after the season, Rubin halfheartedly threw his stomped-on hat back into the ring.

"I've been sick a month and a half from the whole thing," he said. "But if Kosloff called me back tomorrow, I'd swallow my pride."

The call never came.

Rubin returned to Miami, opened an IHOP restaurant, later became a stockbroker, and then, in another incongruous career move, became a social worker.

He is 84 now and, according to Love, the owner's friend, in failing health. For a while, every time an NBA team went on a big losing streak, Rubin's telephone would ring.

But it's been 20 years since he has talked with a sportswriter, and he didn't respond to any of the many messages left on his answering machine for this story.

"It was all terribly difficult for him," Love said. "It was just easier for him, I think, to drop out of sight."