Prospect of long trial helped drive NFL settlement

Soon after being tapped to preside over the concussion-related lawsuits filed against the National Football League by its former players, Judge Anita B. Brody called about a dozen lawyers in the case to her chambers in Philadelphia's federal courthouse.

Soon after being tapped to preside over the concussion-related lawsuits filed against the National Football League by its former players, Judge Anita B. Brody called about a dozen lawyers in the case to her chambers in Philadelphia's federal courthouse.

Brody knew the sport - her grandson is a standout high school player - and with 30 years as a judge, she knew the law. From any view, she told the group, it looked like a protracted march toward a trial, with no real winners.

Years of draining interrogations of aging athletes who were fading away. A cloud lingering over every NFL game, maybe every hit.

"This is going to end badly," Brody warned them, according to three people in the room that day.

That was the backdrop that led to Thursday's surprise $765 million settlement. Urged by the judge and quietly negotiated behind the scenes, the announced deal was a tightly choreographed pact that seemed to appease most of the parties. But not all.

The players will get $675 million - half within three years - to compensate retirees of any era who have documented brain damage. An additional $75 million will be set aside for exams and medical monitoring of all players now retired.

In turn, the NFL escaped what was potentially the biggest public relations challenge of its existence, and without having to admit or address the players' key contention: that league executives suspected or knew each skull-shaking hit to a player's head was probably causing lifelong damage but ran them back onto the field again and again.

As the dust cleared Friday, hurdles remained. The judge still must approve the agreement, OK the lawyers' fees, and appoint a claims administrator to decide how much each player deserves. Brody will also schedule a "fairness hearing," probably this month, to let opponents of the deal speak up.

Some retirees weren't waiting to object.

"Big loss for the players now and the future!" Kevin Mawae, former president of the players' union, tweeted, noting that the NFL was on pace to make $27 billion over the next two decades - more than 25 times the settlement.

Brent Boyd, a lineman for the Minnesota Vikings in the 1980s, said the deal wasn't the groundbreaker the lawyers claimed.

"The players are left at the same station we got picked up at," Boyd said in a phone interview.

Boyd, 56, said he was diagnosed in his late 40s with early-onset dementia and, later, Alzheimer's. But league doctors disputed his claim that his condition was related to his playing days, he said, and he gets only $1,500 a month in disability.

A Reno, Nev., resident, Boyd said it would be cruel and traumatic to subject players like him to more medical exams and second-guessing. He also fears older, more frail players - or their widows - will face the same sort of obstacles when they try to get compensation.

He believes hundreds of other ex-players will oppose the agreement. Those who do could opt out of the class and launch lawsuits on their own.

"In the past, it was delay, deny, and hope we die," Boyd said, repeating words he's said many times since he became one of the first players to raise the issue, testifying in Congress in 2007. "This proposed settlement is exactly along those same lines."

The lawyers and mediator stressed the benefit of reaching a compromise that could quickly help players.

Jeffrey Pash, an executive vice president for the league, also called it "an important step that builds on the significant changes we've made in recent years to make the game safer."

Sol Weiss, a Philadelphia lawyer and co-lead counsel in the case, said many players didn't comprehend the details. According to Weiss, if Boyd has a qualified physician's diagnosis, he won't need to be tested again.

"The reason we settled is to help this [kind of player] who had a problem right now," Weiss said. "He gets immediate help; there's no interference from the NFL."

On Friday, Weiss held a conference call with about 60 retired players. He said most were pleased with the terms.

"This was not a four-week trial after five years of discovery, where there's appeals that could go on," the lawyer said. "This is a resolution where both sides compromised to get this started now rather than way down the road. That's what a settlement is."

Andrew Brandt, a former executive with the Green Bay Packers, said no deal was likely to please all of the players, particularly those who signed on to the case without any symptoms of brain injury.

Most of the 4,500 plaintiffs weren't claiming to have provable brain damage. Instead, they joined the class by filling out a seven-page boilerplate form in which they asserted they played in the NFL and had had at least one concussion.

"In some sense, [the agreement] is good news for players who are truly suffering," said Brandt, a lawyer who runs the Jeffrey S. Moorad Center for Sports Law at Villanova University. But, he added, "I think a lot of plaintiffs in this case were not."

Still, the settlement is not likely to push the issue out of the spotlight, according to Doug Smith, director of University of Pennsylvania's Center for Brain Injury and Repair.

"This actually brings it forward," Smith said. "Everybody, including the owners, agree there is a problem, even if the owners did not admit to any wrongdoing. It seems like they do endorse the concept that getting hit on the head a lot is not a good thing."

The pact sets specific medical criteria and payouts for retirees or their families who meet them: $5 million for Lou Gehrig's disease; $4 million for deaths from chronic traumatic encephalopathy, a brain injury linked to concussions; $3 million for dementia.

Approval of those payouts is expected to fall to a third-party claims administrator appointed by the judge. The same process has been used to compensate plaintiffs in other high-profile cases, including claims made after the 9/11 terror attacks and Hurricane Katrina.

The NFL will also pay the plaintiff lawyers' fees, on top of the settlement fund. That figure is likely to be revealed in coming weeks.

Lawyers in similar class-action or mass-tort cases typically collect a fee equal to a third of the settlement. This litigation, consolidated under Brody in February 2012, was shorter than most.

Michael Boni, a class-action lawyer in Philadelphia, said he still would expect the plaintiffs lawyers' take to be near $100 million. "The plaintiffs [lawyers] are going to certainly ask for a seventh," said Boni, who is not involved in the case.

Weiss declined to discuss the fee negotiations, but said most of the money would go to lawyers in the 11 firms that steered the national litigation and helped craft the settlement. Some might also get a second payment if they negotiated a fee from their clients, he said.

An additional $10 million is to be spent by the NFL on education and research, most likely targeted at young athletes.

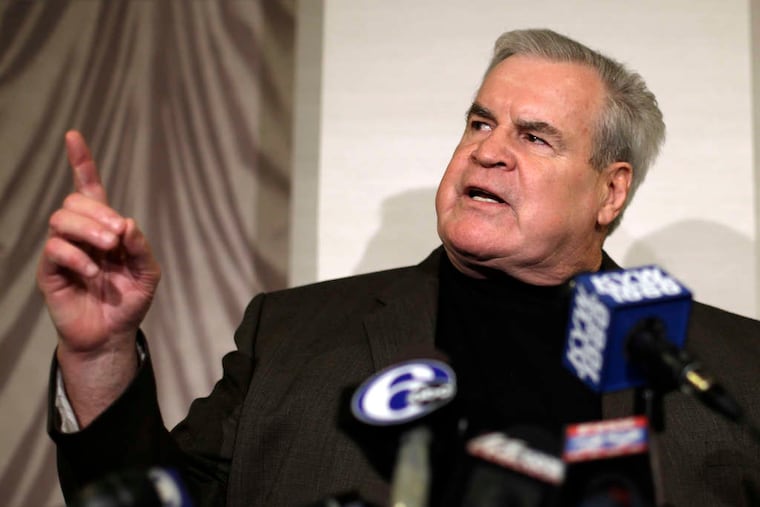

Bill Bergey, the linebacker who anchored the Eagles defense in the 1970s and joined the lawsuit last year, said he was heartened by the agreement.

"The money isn't the important part," Bergey said Friday. "There are a lot of players out there, people I played with, who need the help desperately."