Area vets recall freezing Battle of the Bulge

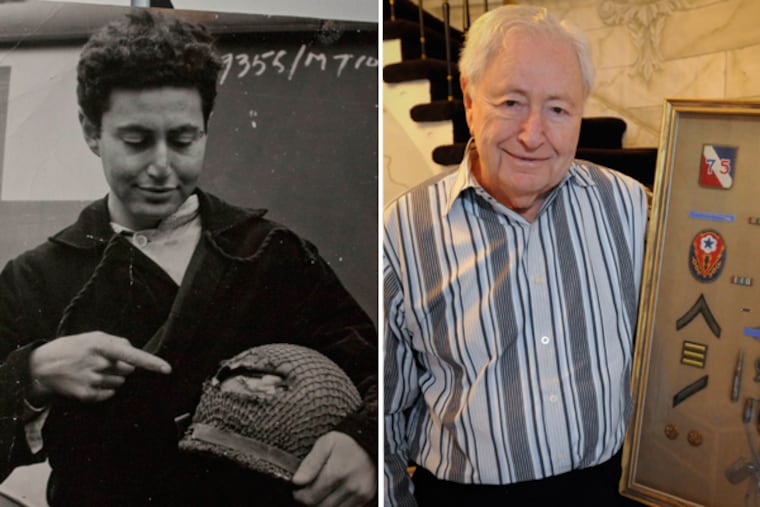

Leonard Becker felt the blow to his helmet and was sure his luck had run out. He was the only member of his 12-man squad who hadn't been killed or wounded as enemy tanks shelled the snowy Ardennes forest during the Germans' last-ditch effort to stop the Allies' advance during World War II.

Leonard Becker felt the blow to his helmet and was sure his luck had run out.

He was the only member of his 12-man squad who hadn't been killed or wounded as enemy tanks shelled the snowy Ardennes forest during the Germans' last-ditch effort to stop the Allies' advance during World War II.

So when Becker removed his helmet and saw the jagged gash through the metal, he sat back and waited to die. He couldn't bring himself to feel the back of his head.

Across the Philadelphia area and South Jersey, the snowflakes and nip in the air are triggering deep-seated memories of an ever-shrinking number of World War II veterans who fought the Battle of Bulge, which started 69 years ago today.

Looking from their homes at snow-covered yards, they're reminded of the bodies of dead soldiers frozen like statues, ice in their canteens and cold so bitter their skin would freeze to the barrels of their guns.

Becker, 90, of Wynnewood, was pleasantly surprised to find himself still alive 10 minutes after the shell exploded over him.

Evacuated by medics with wounds to his head, face, and shoulder, he's often thought of that close call and the shrapnel-torn helmet that he donated to the National Museum of American Jewish History in Philadelphia.

"As a youngster, you can't wait to see the excitement of action," said Becker, who later invested in Philadelphia-area real estate and owned shopping centers and office and apartment buildings. "But once you're there, it was just no fun to see buddies hit, some killed and captured."

Another Army veteran of the battle, Elmer Umbenhauer of Cape May Court House, recalls the house-to-house fighting in Nenning, Germany, and the unrelenting cold that went through to the bone. "It was the luck of the draw whether you made it or didn't make it," said Umbenhauer, 88, a dentist and retired Merck & Co. Inc. clinical research director.

And Army tank commander Ed Lambert of Collingswood remembers losing three tanks in the war, the last one during the Battle of the Bulge, outside Bastogne, Belgium. It was hit by an artillery shell.

"Our Sherman tanks were iron caskets," said Lambert, 89, retired manager of merchandise receiving for the now-defunct Strawbridge & Clothier. "None of my original crew survived" the war.

Nearly seven decades ago, the Allies were quickly moving toward Berlin when the Third Reich struck with a vengeance in what became the Battle of the Bulge, fought from Dec. 16, 1944, to Jan. 25, 1945.

The battle was the largest and most costly of the war for the Americans, with nearly 90,000 casualties, including 19,000 killed.

The German offensive was intended to breach the Allied line of American and British troops posted in the forested Ardennes mountain region during a snowy overcast period that prevented air support and resupply.

Becker hoped to shoot a camera instead of a rifle when the war broke out. He had been a photographer for magazines and newspapers at Overbrook High School and Temple University and freelanced photos for The Inquirer, so he thought he'd try his hand at it in the Army.

It wasn't to be. The Army needed more foot soldiers, and he eventually found himself in the path of a German onslaught that created a bulge the Allies tried to push back.

After his helmet was hit with shrapnel, Becker wondered what he should do. "I remembered that we were instructed to take our sulfa tablets with plenty of water to prevent infection if wounded, so I put several in my mouth and unscrewed my canteen for the water but was frustrated because the water was frozen solid by the extreme cold," he said.

"I then also remembered that if wounded, we should place a tourniquet between the heart and the wound, so I was going to put one around my neck, but then I realized I might choke."

About that time, two Army medics found him and escorted him to the rear, where an ambulance was waiting to take him to a hospital.

"And there I witnessed a most unusual sight," he said. "I stepped into the ambulance and . . . saw three captured wounded German soldiers with the swastikas on their helmets waiting to also go back to our hospital.

"Suddenly, the war no longer made any sense to me because if we had encountered each other five minutes earlier, we would have tried to kill each other . . . and now we were exchanging icy glares," Becker said. "I guess that war can make strange bedfellows, but I sure was confused as an 18-year-old Jewish boy from Philly."

Umbenhauer was 18 in 1943 when he joined the Army, and he found himself at Nenning the following year.

GIs had pushed German troops from the town three times and were forced out three times. In a fourth attempt, Umbenhauer's fresh unit finally held the town.

"It was our first time in combat," Umbenhauer said. "There was nothing but mass confusion.

"Our company commander was killed in the first five minutes," he said. "There was house-to-house fighting, and you never knew what was behind the next door."

The severity of that winter and biting wind is one of the memories he'll "never forget. We'd have snow up to our knees and had no way of getting warm," Umbenhauer said. "If I'm sitting with my kids and there's a terrible snowstorm, I'd say, 'Look out there; that's the way it was during the Battle of the Bulge.' "

Lambert has similar memories. "We didn't have any heat in the tank," he said. "My toes have been cold from the time I came home.

"Any time the temperature is low like this," he said, "I wear heavy-gauge socks."

Lambert's tank was hit near Bastogne, where the American commander had once famously rejected the Germans' call for surrender with one word: "Nuts."

"I was with Gen. George Patton," said Lambert, whose son, Gary, served during the Iraq War. "He was a crazy man but anything that would get us the hell home, that was OK with me."

When the war ended a few months later, the survivors were glad to be back home. "I think the military training does a lot for anybody when they're a youngster," Becker said. "It gives them an appreciation for a hot meal instead of a cold C-ration."

856-779-3833 InkyEBC