For a family in church sanctuary, a legal way out?

"We're doing everything we can on our end, and we're seeing a great deal of resistance on ICE's part," said lawyer David Bennion, who represents the family of Carmela Hernandez. "It's a single-minded focus on deporting everyone they can, without regard for mitigating factors."

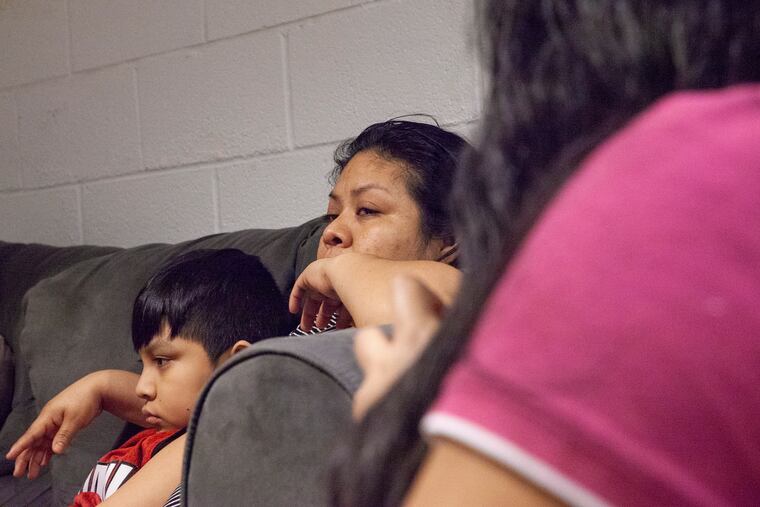

Since December, when the weather turned and temperatures fell to freezing, through the emerging warmth of spring and summer and now fall, Carmela Apolonio Hernandez and her four children have stalled their deportation to Mexico by living in the basement of a North Philadelphia church.

Sanctuary, though, is at once solution and problem, offering protection from immigration authorities while alerting those same enforcement agencies to their exact location. It comes without time limit — a man in Arizona has spent two years and four months inside a Phoenix church.

Walking through the welcoming doors of a house of worship is one thing, as done by 51 people in sanctuary across the country. Finding a safe way out is another.

But for Hernandez, an earlier, hard experience in the United States could offer the family a legal route out of the Church of the Advocate — if the government approves.

Hernandez, 37, has applied for what is called a U visa, which can be granted to people who have been the victims of certain types of crimes in America, and who help police investigate and prosecute the criminal activity, her lawyer confirmed.

It's the same type of visa application that last year enabled an undocumented Mexican immigrant — who had been stabbed in an assault years earlier — to end 11 months of sanctuary inside the Arch Street Methodist Church in Center City.

"I tell all my clients, 'If we don't fight, we can't win,' " said David Bennion, who represents the Hernandez family.

Bennion said Hernandez was a victim of attempted extortion, which occurred last year when she was living in New Jersey.

The list of qualifying offenses is broad, ranging from murder to perjury to stalking. The visa is valid for four years, and after three, the holder can apply for lawful permanent residence in the U.S.

A spokesperson for U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services said the agency does not confirm or deny whether someone has applied.

Congress created the U visa in 2000 with the goal of strengthening the ability of police agencies to investigate and prosecute cases of domestic violence, sexual assault, and trafficking — while protecting victims who suffered substantial mental or physical abuse.

A 2014 study in Arts and Social Sciences Journal found the issuance of the visas had done that, enhancing the justice system's ability to detect, investigate, and prosecute crimes, and making communities safer overall.

The government issues a maximum of 10,000 U visas a year, with additional applicants being placed on a waiting list. The timing for the Hernandez family is far from clear, given the backlog. Last October, Javier Flores Garcia left Arch Street Methodist after being granted deferred action, which allowed him to live and work in the U.S. while awaiting approval of a U visa.

Today 14 men, women, and children are in sanctuary in Philadelphia, more than in any other city in the country.

Hernandez and her children — Edwin, 9; Yoselin, 12; Keyri, 13; and Fidel, 16 — have been there the longest. They fled to the United States in August 2015, after being threatened by the same drug criminals who had killed her brother and two nephews. The family was denied asylum, and took sanctuary only days before their Dec. 15 deportation date.

The children have been able to attend public school, left alone by agents from Immigration and Customs Enforcement, known as ICE. Carmela has not been off the church grounds, and lately has been sick, she thinks from the dampness of the weather or the stress.

"Not knowing when we're going to be able to get out has been the hardest part," she said in an interview.

Still, she swears she'll never give up, never put her children in danger by returning to Mexico.

Bennion said law enforcement officials in New Jersey certified that Hernandez was in fact a crime victim, and he filed her visa application in March. He's now submitting additional information to USCIS to support approval of the visa.

"We're doing everything we can on our end, and we're seeing a great deal of resistance on ICE's part," Bennion said. "It's a single-minded focus on deporting everyone they can, without regard for mitigating factors."

An ICE spokesperson declined to comment, citing privacy restrictions.

Only the truly desperate take sanctuary, trying to forestall deportations that they say would split them from their children or put them in danger in their homelands, supporters say. It's a last-chance gamble, a means to buy time and avoid arrest by ICE agents who are officially dissuaded from making arrests at churches, schools, and hospitals.

It's not always successful. Some people end up leaving sanctuary when the isolation becomes unbearable, or when they exhaust their appeals.

"Where do you go when sanctuary fails? I think it is a place called 'Off the map,' " said Hilary Cunningham, an immigration scholar at the University of Toronto.

Some try to live so quietly as to go unnoticed by police and government agencies, Cunningham said. Others embrace "protective undergrounds," conducting their lives strictly within a network of trusted friends. Some, fearing they could be killed in their homelands, move to a third country.

"The end of sanctuary doesn't always mean you are never going to get picked up by ICE again," said the Rev. Shawna Foster, a movement leader at Two Rivers Unitarian Universalist in Carbondale, Colo. "It doesn't mean you're in the clear."

For instance, a Mexican immigrant left sanctuary in Denver in 2015 after being assured by ICE that he was no longer an enforcement priority — only to be detained, scheduled for deportation more than a year later, and finally saved by a judge who ordered a two-year stay of removal.

Hernandez's relatives, she said, were taxi drivers, killed when they were unable to pay an extortion fee. After she and her elder daughter were threatened and assaulted by the same gangsters, the family fled north, approaching U.S. authorities near San Diego and asking for asylum. After three days in detention they were released to the care of a relative, an American citizen in Pennsylvania.

The family later settled in Vineland.

Hernandez is appealing the denial of asylum in federal court. And she's seeking relief before the Board of Immigration Appeals, based on a recent Supreme Court ruling on the handling of key deportation documents.

"She's been very courageous," Bennion said. "She understands, in some ways more clearly than I can, how she's not been treated right, how her rights have been violated. She basically said: 'No, I'm not going to accept this. I'm not going to be pressured or shamed.' "