Expert sees no link between vaccines and autism

They liken him to a prostitute. Someone with blood on his hands, who doesn't care about the health of children.

They liken him to a prostitute. Someone with blood on his hands, who doesn't care about the health of children.

Those are among the insults that Paul Offit gets by e-mail each week at Children's Hospital of Philadelphia.

He should probably expect to start getting a lot more.

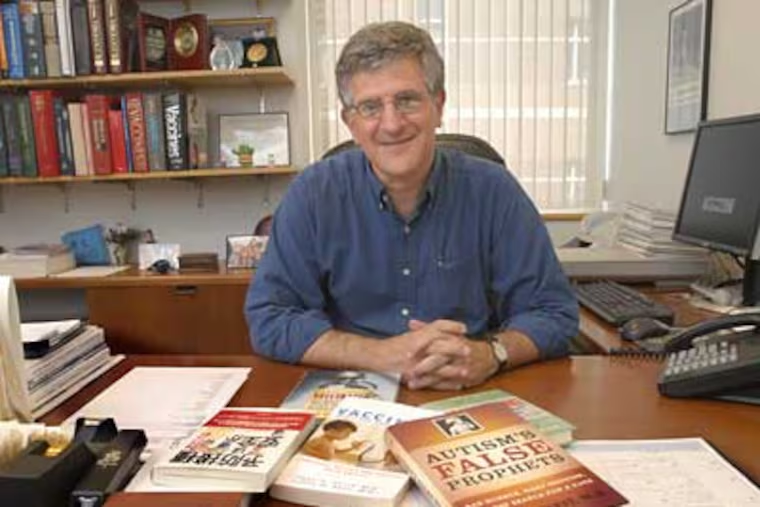

Offit, 57, has been defending the safety of vaccines for years, in response to beliefs that they are tied to autism-related disorders. He continues in the same vein with his new book - Autism's False Prophets: Bad Science, Risky Medicine, and the Search for a Cure - which is already generating heat.

Offit, director of the Vaccine Education Center at Children's and a leading expert on infectious diseases, is among many physicians who defend vaccines. The mainstream scientific and medical communities overwhelmingly agree there is no evidence that vaccines cause autism, though the topic continues to receive study.

But Offit is arguably the issue's most public face. After spending much of his career on vaccine research - a choice that proved unexpectedly lucrative - he now devotes most of his time to teaching and writing on vaccines.

Offit doesn't think any of his critics mean him real harm, though he was rattled once when a caller knew his children's names and where they went to school.

"We put a new security system on our house as a way of celebrating the launch of this book," Offit said during an interview in his office. "Which I think most authors don't do. Maybe Salman Rushdie."

Like global warming and stem-cell research, the topic of vaccines and autism is one that straddles the realms of science and politics.

Diagnoses of autism and related neurological conditions have been increasing for years, to a rate of 1 in 150 children. Some forms can exact a terrible toll on families.

The symptoms arise in early childhood. The timing coincides with the administration of vaccines, so some parents and advocates see a causal link. Some have blamed thimerosal, a mercury-based preservative that was used in small amounts in some vaccines; others blame the vaccines themselves.

Yet thimerosal was removed from all vaccines except some that protect against the flu, and autism rates continued to rise - one of the points Offit makes.

One outspoken critic is an Oregon resident, J.B. Handley, a parent of an autistic child and cofounder of Generation Rescue, a nonprofit group devoted to autism.

Asked about Offit, Handley called him "morally reprehensible" and a "pseudo-scientist."

So why does Offit do it?

Chiefly, he worries that some parents will choose not to inoculate their children, allowing for the resurgence of long-forgotten diseases. Indeed, the government reported 131 cases of measles for the first seven months of this year, the highest number for that period since 1996. Nearly half of the patients had not been vaccinated for religious or philosophical reasons. Moreover, Offit doesn't want the study of an unlikely vaccine-autism link to siphon funds from other research.

During the interview, the pediatrician spoke rapidly and with conviction, shifting between puzzlement and sadness when discussing the debate. One thing he is not: deterred.

"I don't need this," he said. "I do it because it's the right thing to do, and somebody should do it."

Offit and his opponents do agree on one reason that he feels so strongly about vaccines: He helped to invent one himself.

In 1979, while he was a senior resident in Pittsburgh, Offit was unable to save a nine-month-old child who died from an infection of the microbe rotavirus.

He knew that the widespread ailment caused diarrhea and vomiting, killing a half-million children each year worldwide through dehydration. In the United States, most children are saved with proper treatment, yet here was one who died at a fully equipped hospital.

So when Offit came here, he joined forces with Fred Clark and Stanley Plotkin, Philadelphia researchers who were already at work on finding a rotavirus vaccine.

After years of study and testing, the end result - dubbed RotaTeq by Merck, the eventual manufacturer - was approved in 2006.

It seems to be working, according to preliminary data.

During the winter and spring of 2007-08, the rate of rotavirus infections plummeted by more than 50 percent compared with the previous 15 winters - though most children had not yet received all three doses. Many had not gotten any, yet appear to have been protected because those who did were less likely to transmit the disease, the government believes.

Children's Hospital sold its interest in RotaTeq in April for $182 million, and a portion went to the three co-inventors named on the patent. Offit will say only that his share was "substantial."

His opponents say his earnings make him unable to provide an unbiased defense of vaccines. Yet RotaTeq came years after concern over vaccines and autism began, and it never contained mercury.

Offit says he was drawn to the project in 1981 because of the challenge of tackling a global scourge, not because of any hope of a big payoff.

"I love the logic of the anti-vaccine people," Offit said. "I work on a vaccine for 25 years that has the capacity to save 2,000 lives a day, so that I can make money, so that I can lie about vaccines, so I can hurt children."

And plenty of parents bear him no ill will.

"I admire a person who's willing to get up there and stick his neck out for things he believes in," said Kathleen Seidel, mother of a teen with Asperger's syndrome, a related disorder. She runs the blog www.neurodiversity.com.

Plotkin, Offit's co-inventor and former boss, lauds his teaching efforts and his "intestinal fortitude" but worries about his shouldering such a public burden.

"I have talked to him about trying to find other people, younger people who will also take up the cudgel, so he is not the most obvious target," said Plotkin, who also developed the rubella vaccine.

Offit said he doesn't read any of what's posted about him online. He leaves that to his wife, Bonnie, who is also a pediatrician. She admits that some of it makes her "a little nervous," but said she encourages him to continue his work.

Not that he never takes a stance against vaccines. When serving on a federal advisory committee in 2002, he voted against recommending the smallpox vaccine because he thought the risks outweighed the benefits.

Offit doesn't dispute that drugmakers fund some studies that find vaccines safe. On the other hand, he notes in his book, some studies that reported problems with vaccines had received funding from lawyers who planned to sue the manufacturers.

Whom should the public believe? The true test of science, he says again and again, is whether it can be replicated.

Last week, yet another study seemed to support his case, in the Public Library of Science ONE. This time, researchers found no link between autism and the measles-mumps-rubella vaccine.

Yet the debate will almost certainly continue.

And Offit is sticking with it.