A look into Kirsch's own troubled identity

In filings before her 5-year sentence, she described a history of emotional distress, shoplifting and family dysfunction.

For an 18th-birthday present, Jocelyn S. Kirsch got breast implants - an operation performed by her plastic-surgeon father.

The day after she graduated from high school, her mother left her behind and took off to California.

Arrested for shoplifting four times, she has admitted stealing merchandise on as many as 100 other occasions without getting caught.

And she hasn't spoken to her only brother in years.

Those are just a few excerpts from the psychologically troubled backstory of Kirsch, 23. Her stunning looks captivated an international audience when she was arrested in December in a bold identity-fraud scam in Philadelphia. The world was still watching Friday when U.S. District Judge Eduardo C. Robreno sentenced her to five years in prison and ordered her to pay about $100,000 in restitution.

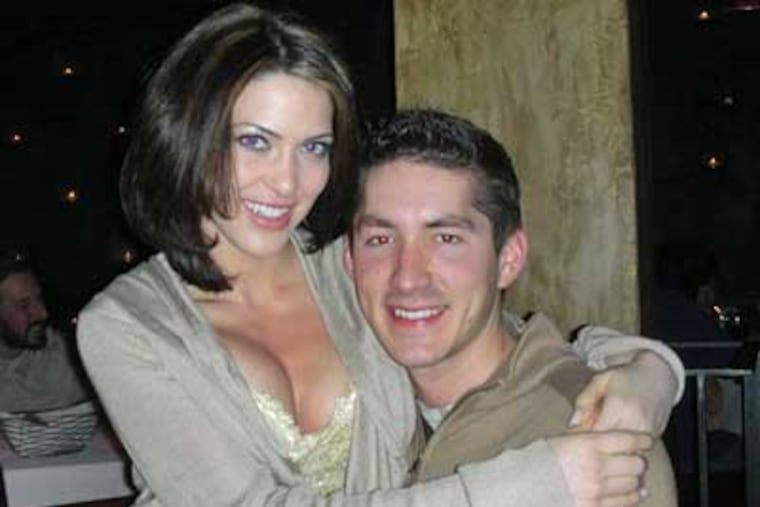

For a year, Kirsch and then-boyfriend Edward Anderton - scheduled to be sentenced Nov. 14 - partied their way through a crime spree that inspired police to dub them the "Bonnie and Clyde" of identity theft. They stole identification from friends, neighbors and coworkers to finance fun - dinners in trendy restaurants, vacations to Paris and the Caribbean, and shopping trips for clothing, electronics, even $2,200 hair extensions.

Psychological and other records introduced in court, however, reveal another Kirsch beneath the high-life veneer: a sad young woman who grew up in a highly dysfunctional family and suffered emotional problems long before entering Drexel University in 2003.

She told one psychologist that her father was "incapable of true emotional connection," and that he and her mother "should never have been parents." She said she was afraid of frogs and of "never learning to be normal."

At her sentencing, Kirsch's mental health was debated at length, based on five psychiatric and psychological reports providing a graphic account of her childhood, her grim relationship with her parents and brother, and her romance with Anderton.

Assistant U.S. Attorney Louis D. Lappen said that Kirsch clearly had "some psychological issues," but that they were not serious enough to warrant a reduced sentence.

Defense attorney Ronald Greenblatt argued that Kirsch was "so clearly mentally ill," with borderline personality disorder, that she deserved a break. For instance, she told people that she had violet eyes because she was of Lithuanian descent, but she was just wearing tinted lenses. She also claimed to be an Olympic pole vaulter.

It was ironic, Greenblatt said, that a woman who had invaded others' privacy by stealing their identities would become the object of a media frenzy, that photos of Kirsch - always smiling, often in a bikini - would be splashed across the Internet.

"It wasn't what the press made this out to be - this girl who had everything doing it for fun," he said. "This was a disturbed person."

Robreno, the judge, sought to balance the issues. He noted the seriousness of Kirsch's crime, yet acknowledged that she had grown up in an environment of "stress and hostility."

He said he "was left to wonder: Was the defendant mentally ill, or was she really self-indulgent?"

In the end, Robreno shaved 10 months off the 70 to 81 months prescribed by sentencing guidelines, and ordered mental-health treatment for Kirsch in prison.

Kirsch is the only daughter of Lee Kirsch, a plastic surgeon, and Jessica Eads, who until recently was a nursing director at a California hospital. The Kirsches moved to North Carolina from Florida in 1995 with their daughter and son, Aaron.

Kirsch's problems began as her parents focused their attention on her brother, who had developed emotional and behavioral problems of his own.

"It is now easy to see," her father wrote to Robreno, "that our family spent a lot of effort attending to Jocelyn's brother, and even though she seemed to be doing fine, we may have well overlooked her difficulties."

In another letter to the judge, Kirsch's maternal step-grandmother, Sandy Cole, recalled her as sullen and unhappy, a troubled preteen with a strange and impolite sense of humor. Even as she blossomed into a beautiful teen, Cole wrote, she remained "very insecure" about her body.

By the time Kirsch was in high school, her parents' marriage was falling apart.

Kirsch told psychologist Allan M. Tepper that her mother, with whom she had lived, left for California the day after she graduated from high school in June 2003.

She did not get along with her brother, a year older than she, so she moved to a neighbor's home.

According to Tepper's report, Kirsch said her brother had been violent as a child. "He basically beat me since I was an infant," she said. It has been years since she has spoken to him.

Kirsch arrived in Philadelphia in September 2003 as a Drexel freshman. During four years there, she visited her father once - in the summer of 2004 when he performed the breast-implant surgery and fixed a bump on her nose. It was a birthday gift, she told psychologist Jeffrey E. Summerton.

She found it "kind of creepy" that her father had operated on her, she said, but he "wouldn't let me go to another doctor."

Another psychologist, Frank M. Dattilio, termed the surgery "a boundary violation" and noted that "the symbolism of her father taking a scalpel to her body was, at the very least, odd."

Cole, the step-grandmother, wrote to the judge, "I truly think she was led to believe by her father that external beauty and living the 'high life' was what she should aspire to."

After a serious relationship with a Drexel graduate who enlisted in the military, Kirsch met Anderton in September 2006. She told him about her shoplifting arrests, and soon they set off on a criminal path.

Kirsch, who suffered from the painful bladder condition interstitial cystitis, said Anderton had held her hand during medical procedures. She also took a number of pain medicines, including OxyContin, Percocet and Xanax, and told psychiatrist Kenneth J. Weiss that she often felt "stoned."

During her time with Anderton, Kirsch told Weiss, her behavior changed.

"She developed an urge to travel, felt impulsive, and did odd things such as painting her apartment neon pink," Weiss wrote in an evaluation. "She and Ed lived in a bubble."

When they were arrested late last year, police searched their Center City apartment and found dozens of fraudulent driver's licenses and credit cards in a variety of names, plus a kit for picking locks, computer software used in identity theft, and a machine for printing ID cards.

Tepper found that Kirsch had a "fractured self-image," an exaggerated need for attention, and chronic feelings of emptiness.

In her letter to Robreno, Kirsch said she had always known that something was wrong with her. Growing up, she said, she felt isolated and misunderstood.

In Anderton, "I thought I'd found the half of myself that was missing," she wrote. "I felt whole. . . . I loved him."

As for their crimes, she continued, "one small thing led to a number of larger indiscretions, and before I knew it, we were doing more and more dangerous things: spending our money recklessly, drinking, lying, stealing."

Kirsch has been in custody since July. In her letter to Robreno, she called prison "horrific" and asked him to remember that she was more than "the sum" of her wrongdoings:

"I am not Bonnie, I am just Jocelyn."