Scarfo pal's conviction offers glimpse into mob

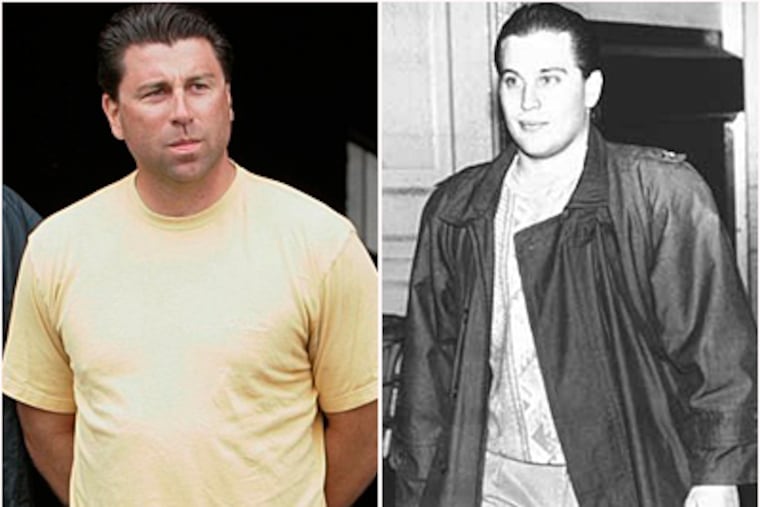

Nicodemo Scarfo Jr. was targeted, but never charged, in a federal racketeering case that resulted in the conviction last week of North Jersey mobster Andrew Merola, one of his best friends and closest underworld allies.

Nicodemo Scarfo Jr. was targeted, but never charged, in a federal racketeering case that resulted in the conviction last week of North Jersey mobster Andrew Merola, one of his best friends and closest underworld allies.

Scarfo, son of jailed Philadelphia-South Jersey mob boss Nicodemo "Little Nicky" Scarfo, was under surveillance and his phones were wiretapped during the investigation, which began about five years ago.

"He was someone we were interested in," said Robert Buccino, chief of detectives for the Union County Prosecutor's Office, which initiated the probe.

Scarfo was not charged when the case was presented to a grand jury, but a sworn affidavit that is part of the case file provides details about how the onetime heir apparent to the Philadelphia crime family was able to operate in North Jersey and, more important, how he managed to reestablish himself in the underworld after he was nearly killed in a botched South Philadelphia mob hit in 1989.

According to the affidavit of a New Jersey State Police organized-crime investigator, Nicodemo Scarfo, from his prison cell in an Atlanta federal penitentiary, was able to take out the equivalent of an underworld life-insurance policy that guaranteed his son would not be targeted again after the failed hit at Dante & Luigi's Restaurant on Halloween night.

The story demonstrates how mob families interact and how underworld alliances are employed, according to law enforcement and underworld sources.

The shooting, one of the most notorious in a series of gangland hits during the Scarfo era, stemmed from a split within the crime family after "Little Nicky" Scarfo and more than a dozen of his associates were sentenced to lengthy prison sentences in 1988.

Weeks before he was shot, the younger Scarfo "learned that there were threats to his life coming from within the family," according to the affidavit submitted by Michael Gregory, an investigator with the state police Organized Crime Control Bureau.

Authorities believe the threats originated with Joseph "Skinny Joey" Merlino, a member of a rival faction of the Philadelphia crime family. Merlino, now serving time for an unrelated racketeering conviction, has long been a suspect but has never been charged in the Dante & Luigi's shooting.

The younger Scarfo was eating dinner in the restaurant with two friends when a man wearing a mask and carrying a trick-or-treat bag walked up to the table, pulled a gun out of the bag, and opened fire.

Scarfo was hit multiple times in the arms and torso but survived. After his release from a Philadelphia hospital, he moved to North Jersey, where he was "put on record as an associate of the Lucchese [crime] family," the affidavit alleges.

That arrangement was set up by "Little Nicky" Scarfo, who had befriended fellow inmate Vic Amuso, a Lucchese crime family boss who was also serving time in Atlanta.

The younger Scarfo's position in the Lucchese organization was solidified several years later, according to the affidavit, when he was "elevated to the role of soldier."

Becoming a "made" member of the Lucchese organization, Gregory noted, "effectively ensured Scarfo Jr.'s protection." Based on underworld protocol, "he was considered 'untouchable' for any additional attempts on his life without the permission of the head of his new family."

The affidavit also notes that while living in North Jersey, Scarfo began associating with Merola, now described as one of the highest-ranking members of the Gambino crime family in North Jersey.

Among other things, Gregory pointed out that Scarfo assumed control of Merola's illegal gambling operations when Merola was jailed for 42 months on a federal extortion conviction in 1998.

While Merola was doing time, Scarfo "made collections and payments in connection with illegal gambling wins and losses and loan-shark debts," Gregory wrote.

The affidavit, submitted in March 2007, pointed out that the investigation focused on that same gambling operation and described Scarfo as Merola's "former partner."

Scarfo, 44, who remains the focus of an unrelated multimillion-dollar financial fraud investigation, was one of several people whose phones were wiretapped during the investigation. He was also spotted meeting with Merola and several other defendants by investigators conducting surveillance.

Merola, 42, pleaded guilty Tuesday to a racketeering-conspiracy charge, admitting he headed a mob crew that Assistant U.S. Attorney Ronald D. Wigler said was involved in a "smorgasbord" of crime in New Jersey.

Twenty of the 23 defendants charged in the case have entered guilty pleas.

The crimes listed in the case included gambling, loan-sharking, extortion, labor racketeering, and a series of financial scams that could have been a Sopranos subplot.

Investigators say Merola and his associates manufactured counterfeit bar codes and used them to steal tens of thousands of dollars in merchandise from stores including Home Depot, Lowe's, Best Buy, and Circuit City.

The scam involved copying and counterfeiting the bar codes of lower-priced items, then returning to the stores and putting the phony codes on more expensive items.

The mobsters would then buy the more expensive items at the lower price.

The indictment listed several items taken from a Lowe's store in Paterson, N.J., between October 2006 and April 2007 as examples of the scheme.

Authorities said Merola and his associates kept the more expensive items and sold them for a price closer to their actual value, or, in an even bolder move, removed the fake bar codes and returned the items for store credit or gift cards equal to their actual value.

The examples cited in the indictment included bar codes taken from a Europro vacuum listed at $49.97 used to buy a Dyson vacuum valued at $549.99; a chain saw listed at $44.97 used to buy a chain saw valued at $374; a paint sprayer listed at $58 used to buy a sprayer valued at $624; and a welding machine listed at $58 used to buy a machine valued at $669.

According to sentencing-guideline recommendations, Merola faces 10 to 12 years in prison and could be ordered to pay fines and forfeitures totaling $350,000.

He remains free on $1 million bail pending his sentencing.