Bad guy-catching billboards began in Philly

Four years ago, Natosha Gale Warner, who works in Philadelphia for the FBI, was batting around ideas with Clear Channel vice president Barbara Bridge about ways to use the company's new digital billboards - the kind that can change images a half-dozen times a minute.

Four years ago, Natosha Gale Warner, who works in Philadelphia for the FBI, was batting around ideas with Clear Channel vice president Barbara Bridge about ways to use the company's new digital billboards - the kind that can change images a half-dozen times a minute.

After discussing using the billboards to publicize a citizen-action program, Warner recalled saying, "How about featuring fugitives, the kind you would normally see in the post office?"

Since that inspiration, hundreds of billboards have sprung up around the country, contributing to the arrests of at least 40 people - most recently a man picked up in Connecticut who authorities believe is the "East Coast Rapist."

On Feb. 28, the very day his picture went up above highways in seven states - including one next to the toll plaza at the Benjamin Franklin Bridge - a crucial tip was called in to Maryland police.

"What took you so long?" Aaron Thomas, 39, reportedly said when U.S. marshals arrested him Friday afternoon in Connecticut. Authorities believe the unemployed truck driver attacked at least 17 women over a dozen years from Virginia to Rhode Island.

This week, drivers on I-95, the Pennsylvania Turnpike, the Admiral Wilson Boulevard, and the Walt Whitman Bridge can catch glimpses of the likes of Cornell Sutherland, wanted for murder, staring back between ads for Mars Needs Moms and March Madness on CBS.

The Philadelphia area has had the lion's share of successes since Clear Channel launched the effort on Sept. 13, 2007, with eight people arrested since then in connection with crimes including operating a Ponzi scheme, drug dealing, rape, and murder.

Clear Channel, said Philadelphia division president George Kauker, has long worked closely with police and firefighters - posting billboard tributes to fallen officers, for example - so getting on board the fugitive billboard idea was "pretty automatic."

The first arrests came quickly. The month after the billboards went up, two fugitives were captured as a direct result of the publicity, the FBI announced.

And then the billboards helped catch a man later convicted of killing a police officer.

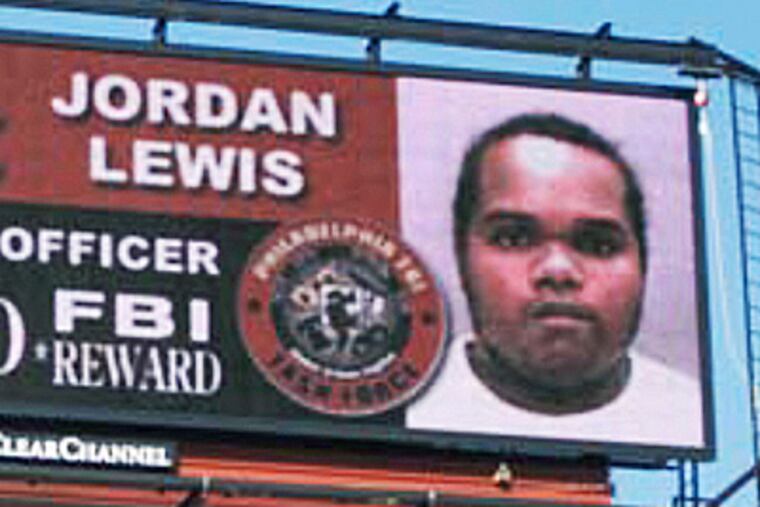

That Halloween, Philadelphia Police Officer Chuck Cassidy was gunned down while responding to an armed robbery, and digital billboards quickly spread the word about the manhunt for suspect John "Jordan" Lewis, who was captured within a week in Miami.

Lewis, who confessed, was sentenced to death in 2009 by a jury.

Early on, Warner, who works as a community-outreach specialist for the FBI, suggested taking the program national, she said.

In December 2007, the FBI announced that the company had agreed to expand the program to 150 billboards in 20 metropolitan areas, from Los Angeles to Tampa, Fla., to Newark, N.J. Since then, other outdoor advertisers have joined in and the program has exploded, with up to 1,500 of the nation's 2,400 digital billboards now available to take part - at no cost to the FBI, according to the agency and the Outdoor Advertising Association of America, a trade group.

The commitment, though, apparently varies greatly. In some places, wanted posters run only when an ad slot goes unsold, said Chis Allen, an FBI spokesman in Washington.

Not so in Philadelphia. Every day, Clear Channel has "wanted" banners in its rotations here, sacrificing considerable revenue, said Kauker.

"Nationally, it's tens of millions of dollars, absolutely," he said, adding that company billboards have also run many Amber Alerts.

Typically, suspects are featured only locally, so mug shots posted in Akron won't match the ones in Albuquerque.

But in January 2009, confessed Ponzi schemer Glyn Richards of Haddon Heights skipped a court appearance in Camden, and the FBI believed he might have fled to Tampa. So Clear Channel put his face on billboards there. Within a few weeks, he was arrested in Tampa, and was later sentenced to 30 years in federal prison.

In summer 2009, the long arm of the law got longer when the search for a serial bank robber spread to billboards in eight Southern states. He was identified within a day and arrested within a month, according to news reports.

And last Aug. 1, the search for the Granddad Bandit - a middle-aged man wanted for holding up more than two dozen banks from New York to Texas - went digital nationally, with a billboard push expanded to 40 states.

Ten days later, Michael Francis Mara, 53, was arrested at his Baton Rouge, La., home and later pleaded guilty to two of the robberies.

Those successes inspired the decision to use billboards to find the East Coast Rapist, Allen said.

While Maryland police haven't said whether the tipster saw the suspect's sketch on TV, in print, online, or on a billboard, it was publicity about the billboard campaign that led to the explosion in media interest, investigators point out.

By far, Philadelphia has had the most success. Among the featured fugitives found were armed-robbery suspects Ernest Avery and Brian Leatherbury, homicide suspect William Worrel, and accused drug dealer Gerald Williams.

But sketches of the so-called Kensington Strangler or fuzzy video images of the suspect in the rape and killing of Northern Liberties waitress Sabina Rose O'Donnell never made the billboards.

That's because drivers have only an eight-second glimpse, said J.J. Klaver, the FBI's Philadelphia spokesman.

Warner, 39, who started with the FBI as an intern out of Benjamin Franklin High School, said she gets "a little ping in her heart" thinking about the program.

"This makes me feel good to know that people are doing the right thing."