West Goshen police chief turns kidney donor

The e-mail that Nancy Gleason received last September was lengthy: a last-ditch plea from a distant relative, writing to ask if she knew anyone who might be willing to donate a kidney to a stranger.

The e-mail that Nancy Gleason received last September was lengthy: a last-ditch plea from a distant relative, writing to ask if she knew anyone who might be willing to donate a kidney to a stranger.

Gleason clicked the "forward" button and typed in her husband's e-mail address. Her e-mail was just one line long: "We're both O-positive. I'm in if you are."

Eight months later, Chief Joe Gleason of the West Goshen Police Department was heading into surgery at the Mayo Clinic, about to give a major organ to a woman he had met two days before.

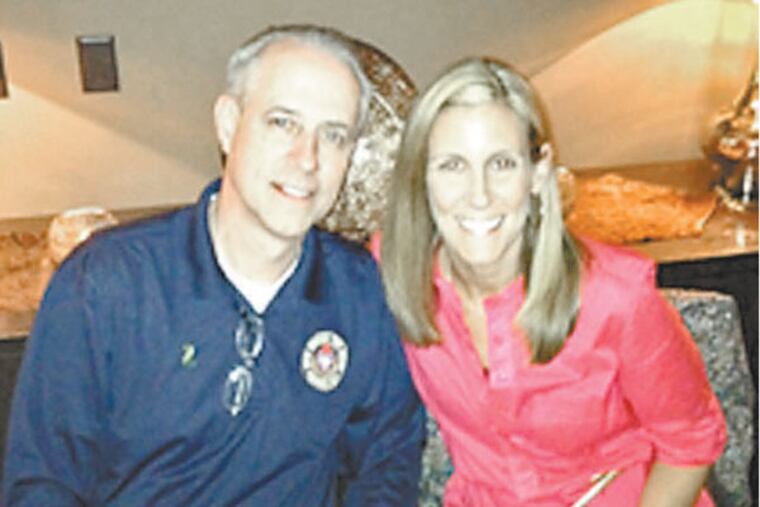

Gleason, 55, who has led the West Goshen department since 2011, gives new meaning to the term unassuming. Ask him to talk about himself and he'll smile and say he just doesn't like to. Married to Nancy for 30 years, a father of three, he worked his way up from traffic cop to chief of police over a 31-year career.

"I have a lot of pride in this place," he said.

Last September, his nephew's wife included the Gleasons on a mass e-mail on behalf of her sister, Megan Comerford, who had been found to have a kidney disease in 2002.

A mother of three girls who owns a French-inspired restaurant with her husband in Decatur, Ill., Comerford had been on dialysis for almost a year and on an organ-transplant list for nearly three. When her sister sent the e-mail, her kidneys were functioning at less than 15 percent.

"Other donors had gotten pretty far in the process, and there was always something that wasn't going to work," she said. "I thought, I can't get attached to it until I'm actually in pre-op, because so much can change."

Comerford, 36, had dealt with her condition for nearly 10 years and had taken well to dialysis. But the disease was taking its toll.

"I was going back and forth from doctors' offices, back and forth from dialysis," she said. "It was a full-time job, maintaining your own health care."

Halfway across the country, all five Gleasons had submitted their blood for testing. Doctors quickly identified Joe Gleason as a potential match for Comerford, and he spent most of January undergoing test after test to confirm their compatibility. By March, it was official: Gleason was a match, and he called Comerford to celebrate. It was the first time the two had spoken.

In late April, Joe and Nancy flew to Rochester, Minn., to the Mayo Clinic, where the transplant would be performed.

"We met them at a restaurant," Comerford said. "We kept looking at everyone walking in, asking, 'Is that Joe? Is that Joe?' "

Gleason shrugged off concerns about the seriousness of the operation. He and his wife, he said, were "brought up in families where you just did for others."

"There were skeptics, people that looked at me like I had three heads," he said. "People say, if you give away one, what happens if yours goes bad? But if you think like that, you're never going to do anything for anyone."

Gleason and Comerford went into surgery May 1. By that evening, they were walking through the halls of the Mayo Clinic together, leaning on walkers, getting to know each other. Within two days, Gleason was out of the hospital, walking five miles a day and drinking "tons of water" - doctor's orders, he said.

Within 81/2 weeks, Comerford participated in a triathlon. She sent Gleason a photo after she crossed the finish line.

It has been seven months since the transplant, and Comerford and Gleason are doing well, with no complications.

"My disease involved a gradual decline in kidney function, so I never felt that bad, but having the transplant, I feel so much better. It's amazing what having clean blood does for the rest of your body," Comerford said, laughing.

Gleason, for his part, says he recommends the surgery to anyone thinking about donating an organ.

"It's been a wonderful journey," he said. A clock with a photo of the Comerfords sits on his desk - a gift from Megan Comerford, he said, to thank him for "the gift of time."

The families still keep in touch. Two weeks ago, the Comerfords were on hand when the Chester County Fraternal Order of Police lodge presented Gleason with a humanitarian award for his donation.

Gleason, true to form, said he did not want the attention.

"I'm still investigating this conspiracy that led to me getting that award," he said, laughing.

Comerford says he deserves all of it and more.

"I can't ever repay him for this gift," she said.