Squabbles mar N.J. forest plan

For 15 years, certified forester Bob Williams watched over 5,000 acres of woodlands and wetlands in Atlantic County's Estell Manor. He thinned trees, conducted controlled burns, and planted and fenced seedlings of the increasingly threatened Atlantic white cedar.

For 15 years, certified forester Bob Williams watched over 5,000 acres of woodlands and wetlands in Atlantic County's Estell Manor. He thinned trees, conducted controlled burns, and planted and fenced seedlings of the increasingly threatened Atlantic white cedar.

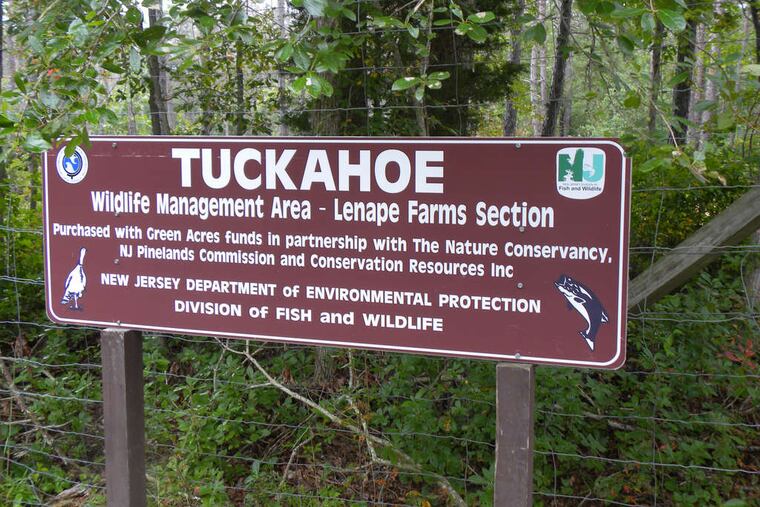

When the Christie administration bought the land from Lenape Farms Inc. eight months ago, Williams and the landowners who hired him were lauded by state officials for encouraging forest regeneration, reducing wildfire hazards, and protecting wildlife.

Last week, the forester returned to the site to find sections of the $10,000 fencing down, deer prints in the mud, and many of the seedlings gone.

"What else haven't they [state officials] done?" Williams asked about the new Tuckahoe Wildlife Management Area. "They put up beautiful signs and built a parking lot, but what about the resource?"

"If they believe in buying land to stop people from building on it, then abandoning it, they should say so," he said. "Everybody agrees we need stewardship, but we end up with endless bickering."

The bickering over forest management erupted anew last week when Gov. Christie conditionally vetoed the Healthy Forests Act, a bill that has divided environmentalist and conservationist groups over how best to oversee 600,000 acres of aging state-owned forests.

The measure called on the Department of Environmental Protection to develop stewardship plans that would include thinning of forests and selling of timber to pay for the program and habitat restoration.

Its supporters say tree harvesting is necessary for healthy forests, which are under attack by invasive plant and insect species. The state's aging woodlands also are overpopulated by deer, and its dense canopies cut off natural light needed for new growth, they say.

Opponents, such as the New Jersey Sierra Club, say "the bill creates an open season on our forests and public land," does not include adequate protections for natural resources, and contains no enforcement mechanism.

Christie's main objection was a provision that would have required the nonprofit Forest Stewardship Council to approve the DEP's plans. That condition won over some environmental groups that were concerned the measure would open forests to commercial logging.

But the governor said the requirement would cause the DEP to "abdicate its responsibility to serve as the state's environmental steward to a named third party." He suggested the bill give the DEP the option of obtaining certification from an outside party while retaining its authority.

"Our New Jersey forests have been neglected for decades," said State Sen. Bob Smith, (D., Piscataway), a bill sponsor. "We have a real crisis, and the whole point of the legislation is finding a creative way of managing the forests."

Populations near the woodlands are vulnerable to fires but have been spared so far this year because of heavy rains, he said.

"The legislation is intended to say to the DEP, 'Come on, manage the forests. You have the authority. Do your job,' " Smith said. "If the [DEP] commissioner states that an outside review from an appropriate forest entity will be gotten, that might go a long way to solving this."

The Legislature can approve Christie's recommended bill changes or let the measure die by taking no further action. An override is unlikely.

Smith said he was studying the constitutionality of the legislation before meeting with both sides of the issue to search for "a reasonable solution."

Pennsylvania, Maryland, and other states have programs in which forest stewardship plans are certified by two outside organizations, such as the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) and the nonprofit Sustainable Forest Initiative (SFI).

SFI opposed New Jersey's proposal because it would bind the state forester to a "single forest management standard when other credible forest certification standards exist, including the SFI standard." It called on Christie to conditionally veto the bill and recommend the FSC requirement be removed or include SFI and FSC certification together.

The DEP "has statutory authority to grant logging rights on state-owned forests as a forest management tool," said department spokesman Larry Hajna. "We have had contracts with companies, notably in our efforts to control the Southern pine beetle, to deal with trees damaged or blown down by Sandy, and, more broadly, to control invasive species."

At Double Trouble State Park in Lacey and Berkeley Townships, the state awarded a bid for the removal of white cedars blown down by Sandy so the area could be replanted with that species, Hajna said. And the New Jersey Forest Fire Service has conducted prescribed burns to help "manage competing species and keep forest healthy while reducing wildfire risks."

The state Forestry Service "would do a great job of producing a stewardship plan," said Tim Dunne, a retired resource conservationist with the U.S. Department of Agriculture. "They have the capability.

But "the overzealous tree protectors stand in front of bulldozers trying to stop active forest management and they say foresters are not there to protect the forest," he said. "They call them loggers, and that's like calling doctors undertakers."

The DEP "can and should move forward," said John Cecil, vice president of stewardship for the nonprofit New Jersey Audubon Society. "It doesn't need legislation if it does the right thing in forest stewardship."

The state should offer plans for two forest areas - one in North Jersey and one in the south - following the best science, then execute them, said Les Alpaugh, a retired New Jersey state forester who has a private forest consultant business.

"The [state's] Green Acres program sets land aside, but nobody thought about what to do with it after they got it," he said. "They should have bought the development rights and left more of the land in private hands, where the owners would take care of it."

Whatever course the state takes, funding will be the key. "The reality is that it takes money to manage land," Cecil said. "The state can do whatever it wants, but with shrinking budgets and staff, we see nothing getting done."

Some of the money for the program can be provided by the sale of timber. The legislation "provides the opportunity to offset management costs by responsibly managing a renewable resource and directing any profits back into forest stewardship and habitat conservation," said Kelly Mooij, vice president of government relations for the New Jersey Audubon Society.

Among the concerns of the New Jersey Sierra Club is the effect of logging on park access for recreation and the possibility that money raised would be diverted to the general fund, not used on forestry issues.

The bill "does not include adequate protections for natural resources and has a plan without any rules or enforcement," said Jeff Tittel, director of the New Jersey Sierra Club.

While the groups argue, some tree species, such as the Atlantic white cedar, and animals such as the ruffed grouse and bobwhite quail are being diminished or lost, said Williams, a forester who oversees 125,000 acres of private woodlands.

"We need leadership now," he said. "What we have is a food fight."