Abbie Hoffman's presence still echoes in Bucks County

The gray Toyota Corolla that Abbie Hoffman drove in Mexico during his fugitive years still sits in upper Bucks County, parked on the old farm where he lived and took his own life 25 years ago.

The gray Toyota Corolla that Abbie Hoffman drove in Mexico during his fugitive years still sits in upper Bucks County, parked on the old farm where he lived and took his own life 25 years ago.

"I've been wondering what to do with it," Michael Waldron, Hoffman's former landlord and friend, said last week. "But I'm not sure who would take it."

They still remember Hoffman at the Apple Jack bar in Point Pleasant, where he once shot pool and flirted with women.

"He was pretty rowdy," said a 64-year-old regular, who didn't want to give his name. "He was loud. He was Abbie."

And if the iconoclastic 1960s radical - branded as both a counterculture hero and a publicity-seeking clown - left a legacy in Bucks, perhaps it's undeveloped land. Tracy Carluccio, deputy director of the Delaware Riverkeeper Network, said Hoffman's help fighting a 1980s project to pump water from the river sparked a rebirth of local environmental activism.

On April 12, 1989, the 52-year-old Hoffman was found dead in his Solebury apartment, a converted turkey coop. His suicide was an anticlimactic end for one of America's most recognizable provocateurs, a man who helped "levitate" the Pentagon, dump cash onto the floor of the New York Stock Exchange, and nominate a pig for president in 1968.

His death drew national headlines. But his name carries far less currency today, particularly among Americans born after the baby boom. And yet mention of his name still stirs debate over his legacy in the nation and in Bucks County, where he spent his final years.

Hoffman is most remembered as one of the Chicago Seven, a group accused of inciting riots outside the 1968 Democratic Convention. He had an FBI file thicker than all of his books, including Steal This Book, a best-selling manifesto on how to live free.

"So much of the left was overly serious, and Abbie's gift was his humor and theater and the fact that he was educating people," said Jonah Raskin, a Hoffman friend and author of For the Hell of It: The Life and Times of Abbie Hoffman.

Underground

But Fred Turner, an associate professor of communication at Stanford University, wonders if Hoffman's style "haunts us now."

Turner credits Hoffman for satirical influence on comedians such as Jon Stewart and Dave Chappelle. But he said people "tend to believe that expressing one's opinion in a public place is expressing politics. And that is not in any way expressing politics."

After an arrest for dealing cocaine in the early 1970s, Hoffman had plastic surgery and went underground for nearly seven years. He resurfaced in 1980 and served three months in jail, before settling outside New Hope.

"I understood why Abbie went to Bucks County - because you couldn't find it," his brother, Jack Hoffman, said in a phone interview from Massachusetts, where Hoffman grew up before earning degrees from Brandeis University and the University of California-Berkeley.

A performer

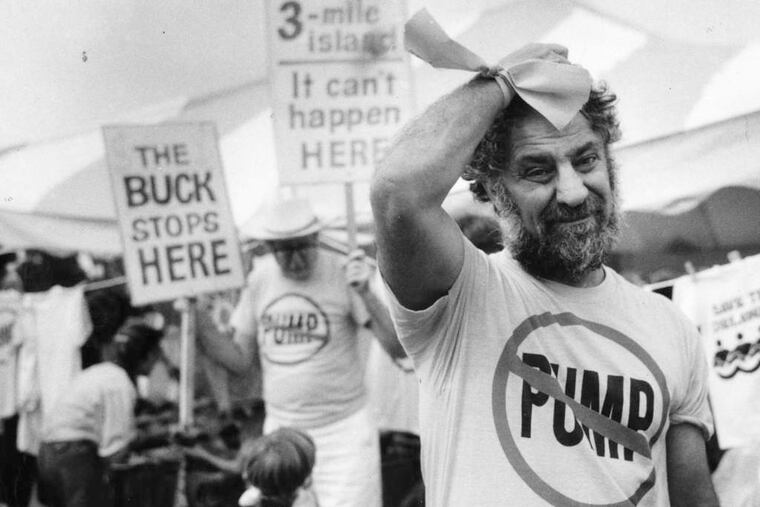

In 1982, Hoffman was hired by the group Del-AWARE Unlimited Inc. to help fight the proposed pump on the river, which would feed water to the Limerick nuclear power plant in Montgomery County.

Carluccio, who was the group's director, said Hoffman attracted much-needed attention to the cause and was instrumental in engaging the larger community.

But Albert Cepparulo, a lawyer who represented pump protesters, said Hoffman "wanted to perform."

He helped lead blockades of the construction site and protests at the courthouse, where he once signed his name on the wall. After an arrest, Hoffman asked Cepparulo - now a Bucks County judge - to represent him.

The writer George Plimpton sent a check to pay Hoffman's legal bills, but Cepparulo said Hoffman was just a sideshow.

"There were so many volunteers that spent years fighting this cause," he said. "And I remember them much more than I do Abbie Hoffman."

The project eventually moved forward despite the opposition; the water started flowing in the summer of 1989.

Hoffman was still lecturing at colleges and writing in the months before he died.

"He had a lot of energy and lots of ideas," said Cheryl Chen, who worked as one of Hoffman's assistants while she was in high school.

Chen remembers getting caught driving without a license with a friend and calling Hoffman from the police station because she couldn't reach her parents.

"He clearly tried to dress respectfully," she said with a laugh. "He drove us home and gave us a lecture about driving without insurance or a license. I remember being surprised by getting that kind of lecture from him."

Waldron, his former landlord, said people visited from all over the world, including the poet Allen Ginsberg. Hoffman once rehearsed his lines as a strike organizer in the Oliver Stone movie Born on the Fourth of July to llamas standing outside his window. One spat on him.

Hoffman, however, had been growing increasingly depressed. He suffered from bipolar disorder and was concerned about growing old.

The last time Jack Hoffman talked to his brother, he told him their mother had been diagnosed with cancer. Later that night, Abbie Hoffman ingested a large amount of the sedative phenobarbital while drinking glasses of Glenlivet scotch.

Despite disbelief among some that Hoffman killed himself - he didn't leave a note - a coroner ruled the death a suicide. The local police department quickly wrapped up its investigation.

"We thought maybe the feds might want to come in and take a look at the computer that was there," said Dan Boyle, a former Solebury police officer who is now a private investigator. "That never happened."

Chen, who now lectures on philosophy at Harvard, said she was in college during the first Iraq War and thought, "What would Abbie be doing in response to this?"

"In the past 15 years, so many crazy things have happened," she added. "I sometimes think, 'What would he be making of all this?' "