It's been 50 years since Martin Luther King Jr. was killed. Are things better or worse?

What would King say about how we've progressed as a nation?

Philadelphia activists, labor leaders, ministers, and teachers will tell you: Of course there has been progress in the 50 years since the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was killed on April 4, 1968.

But they also will say the country has much work to do — not just when it comes to civil rights, but regarding King's eventual focus on economic justice and peace, what he called "the era of human rights."

After all, who remains to benefit from economic policies, neighborhood gentrification, or the public school system of the last 50 years? So many black men are being killed by police, but how does it compare to the days of Jim Crow?

What would King say about how we've progressed as a nation?

Brittany "Bree" Newsome, the North Carolina activist who climbed a flagpole in 2015 to take down the Confederate flag at the Columbia, S.C., statehouse, believes progress has been "minimal." Of the demands made at the 1963 March on Washington — when King gave his "I Have a Dream" speech — only access to public accommodations has been resolved, she said.

"Voting rights, schools, police brutality, and housing still represent unresolved issues of inequality and racism," said Newsome, a filmmaker and activist.

Here are perspectives Philadelphians gave on how far we've come on King's dream.

Racism and racial relations

Corean Holloway was one of nine students to desegregate the all-white school in her hometown of Hemingway, S.C. Today, the Philadelphian says racism is still entrenched.

It may not always be flagrant, like what she witnessed during segregation — public attacks by police with dogs and fire hoses aimed at children — but it can be found in the policies that cities and school districts enact that have a detrimental impact on people of color.

The 24 city schools that were closed in 2013, for instance, "hurt the black children the most," said Holloway, 66. "A lot of those kids had to travel a longer distance to get to school, and it made it harder for the parents for them to go farther away."

When President Barack Obama was elected in 2008, many people heralded a post-racial society, said Raymond M. Brown, 70, a partner in the law firm of Greenbaum, Rowe, Smith & Davis in New Jersey. Brown was one of the students who took over Columbia University buildings in 1968 to protest the school's plans to build a gymnasium in a city-owned Harlem park.

But he says the opposite happened: Obama's presidency "exacerbated racism and struck a nerve."

Now, there's a part of the black community that is feeling "not only hopeless, but under attack," said the Rev. David Brown, community pastor at Wharton Wesley United Methodist Church in West Philadelphia and an assistant professor of communications at Temple University. "Hate groups are rising."

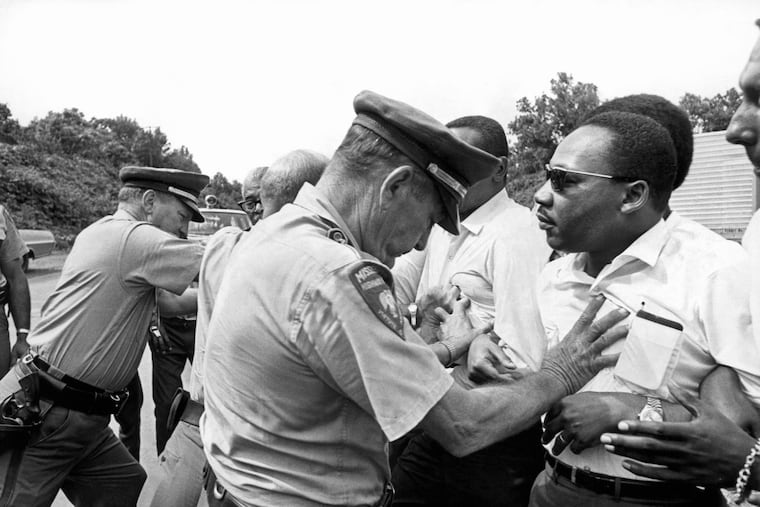

Police brutality and gun violence

"I believe if King were alive today, he would be standing with Black Lives Matter activists, calling for an end to police brutality, an end to the raids in my community; he would echo the call to shut down prisons," said Erika Almirón, executive director of Juntos, an immigration advocacy group. In other words, she believes honoring King's legacy is far from complete.

This week alone, protests continue in Sacramento, Calif., after the March killing of Stephon Clark, 22, an unarmed black man who was shot by police eight times, six in the back.

The repeated deaths of black men at the hands of police "makes me a lot more angrier than I was in the 1960s," said the Rev. William B. Moore, who took part in sit-ins at lunch counters as a college student in Fayetteville, N.C. Now 70, he is pastor of the Tenth Memorial Baptist Church in North Philadelphia.

"You would have thought that things would have improved, but it seems like now, in this environment, we have taken a giant step backward in terms of race relations in many ways. It makes you angry, because it's always the same flippant and frivolous excuse on the part of police that 'I thought it was a gun.' "

Police brutality is just a modern-day form of lynch mobs, said Raymond Brown, the lawyer. In addition, cellphones now reveal to everyone the violence that black people always knew occurred.

But the killings, mass incarceration, and deportations have inspired an urgency to organize and protest, especially by young people, said David Brown, the minister. He credited Florida high school students with energizing talks about gun reform and ending gun violence.

"There's a level of impatience on the part of young people, which I think is healthier," Brown said. "We are tired of waiting. We have people dying now."

Poverty and unemployment

Philadelphia's poverty rate, at 25.7 percent, is the highest among the nation's 10 largest cities, the Pew Charitable Trusts reported last fall, with 400,000 people living below the poverty line — $19,337 a year for an adult with two children. The Center City District compared today's poverty rate with 1970's; depending on the neighborhood, numbers then ranged from 3 percent to 36.2 percent.

"The same poverty that King was concerned with is still here today," said Minister Rodney Muhammad, president of the Philadelphia NAACP. "The civil rights legislation did not have the power to erase poverty."

Muhammad, echoing the Poor People's Campaign of 50 years ago, stressed that poverty isn't just an issue for African-Americans.

"There's a lot of white folks that are being left out, and pretty soon, if we don't join forces and form a coalition, it's only going to get worse. It has less to do with black and white, but more to do with the top ruling class against those at the bottom."

What has definitely changed in 50 years, said John Dodds, director of the Philadelphia Unemployment Project, is the city's manufacturing base: It's pretty much gone.

"The whole Center City boom is not helping lower-income and lesser-educated people," Dodds said.

Political power and gentrification

That Temple University plans to build a football stadium against the wishes of its North Philadelphia neighbors isn't so different from the wrath Columbia drew in 1968 from its Harlem neighbors when it planned to put the gym in a public park, Moore said. Both are conflicts between bureaucracies trying to force their will over poor and working-class communities.

But today's anger isn't just against white political power, Moore said. Despite the large number of black politicians elected in Philadelphia since W. Wilson Goode Sr. became the city's first black mayor in 1984, stadium opponents say today's officials don't advocate for them as black leaders would have in the 1960s.

Moore noted Temple held a March 6 community meeting at Mitten Hall that neither City Council President Darrell L. Clarke nor State Sen. Sharif Street attended. But earlier that morning, Clarke did attend a campaign fund-raising breakfast (up to $1,000 a plate) at the Divine Lorraine sponsored by three developers.

"It's a betrayal and an affront to the legacy of activism that won civil rights for black people," Ruth Birchett, a North Philadelphia resident who organized the Stadium Stompers. "We are void of representation in City Council."

If King were alive today, Moore said, his "Letter From Birmingham Jail" — his essay in 1963 to white Southern ministers — would have to be recast: "I think King would write an open letter to the black politicians in Philadelphia."

Discrimination in housing

It was only seven days after King's assassination that the Civil Rights Act of 1968 — which also included the Fair Housing Act — was signed by President Lyndon B. Johnson.

Last week, Angela McIver, chief executive of the Fair Housing Rights Center in Southeastern Pennsylvania, testified before a City Council committee about redlining practices.

"According to the Center for Investigative Reporting, 50 years after the federal Fair Housing Act banned racial discrimination in lending, people of color continue to be routinely denied conventional mortgage loans at rates far higher than their white counterparts," McIver told a public hearing Thursday. In written testimony, local banking institutions denied they discriminate.

Segregation in education

Though the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision made segregation illegal, Karel Kilimnik, a public education advocate who retired from the Philadelphia schools, says segregation has only intensified.

"Fifty years after King, [public education has] become so much more segregated," said Kilimnik, of the advocacy group Alliance for Philadelphia Public Schools.

Charter schools deplete funds from traditional schools, said Kilimnik, which fuels the expansion of charters while neighborhood schools suffer. And national studies have found greater segregation of students as a result of charters.

Mark Gleason, executive director of the Philadelphia School Partnership, which raises funds to improve education for low-income students, said schools assigned by geography will reflect segregated neighborhoods.

Keeping that in mind, Gleason said, "desegregation shouldn't be the goal. Equity of educational opportunities should be the main goal."