Belfast celebrates Titanic enterprise

The city where the liner was built is looking to tourism.

BELFAST, Northern Ireland - To most of the world, the name Titanic means tragedy, spiced with romance, sacrifice, and luxury. But in Belfast, where it was built, the doomed ship is a triumph of industry, enterprise, and engineering.

The city hopes the rest of the world will soon see it that way, too.

Northern Ireland's capital, scarred by 30 years of Catholic-Protestant violence and mired in Europe's economic doldrums, is gambling on a gleaming new Titanic tourist attraction to bring it fame beyond the Troubles - and a renewed sense of civic pride.

Tying the city's name to a sinking ship is not, apparently, a problem.

"What happened to the Titanic was a disaster," said Tim Husbands, chief executive of Titanic Belfast, a $160 million visitor attraction due to open March 31, ahead of the 100th anniversary of the ship's sinking. "But the ship wasn't."

Colin Cobb, a Titanic expert who leads walking tours of the docks and slipways where the ship was built, puts it even more succinctly: "Tragedy plus time equals tourism."

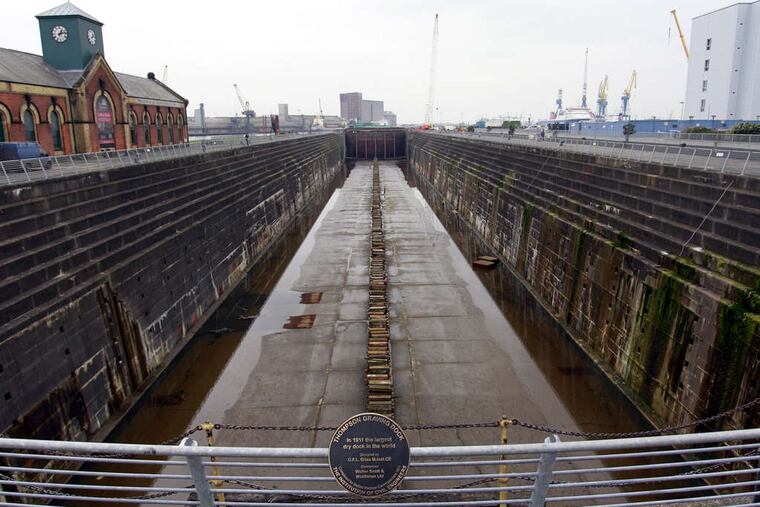

Celebrating the ship and its builders is the aim of Titanic Belfast, a shiny new "visitor experience" whose four prow-like wings jut jauntily skyward beside the River Lagan on the site of the former Harland & Wolff shipyard.

Titanic, then the world's largest, most luxurious ocean liner, left this spot on April 2, 1912, eight days before its maiden voyage from England to New York. In the early hours of April 15, the vessel touted as "practically unsinkable" hit an iceberg off the coast of Newfoundland and sank. More than 1,500 of the 2,200 people on board died.

Belfast mourned - and then, for decades, kept quiet about its link to the tragedy.

"When she sank, it was a huge shock for the city," said Susie Millar, whose great-grandfather Thomas Millar was a deck engineer who perished aboard the Titanic. "For years and years it wasn't discussed. But now, coming up to the 100th anniversary, we've rediscovered that pride in the ship, and we're sharing those stories again."

Belfast is banking on the global reach of the Titanic name. But while millions from London to Beijing have heard of the disaster, few know of the ship's Belfast origins.

"I wish the movie had mentioned Belfast just once," said Titanic Belfast marketing manager Claire Bradshaw. "It would make my job a lot easier."

The new exhibit aims to correct the record, telling the story of Belfast's time as an industrial powerhouse, and the thousands of men who worked for three years to build Titanic and its sister vessels, Olympic and Britannic.

It features 3-D projections and sleek audiovisual displays, as well as a roller-coaster-style indoor ride that swoops visitors around the hull and through the rudder of a replica ship amid the glow of molten rivets and the clang of metal on metal.

The stories of several of the Titanic's builders, passengers and crew are followed through the displays to their often tragic conclusions.

There's also a marine exploration center linked to the work of Robert Ballard, who discovered the wreck of the Titanic at the bottom of the Atlantic in 1985.

And managers hope the 1,000-seat banqueting suite, complete with White Star Line crockery and a reproduction of the ship's iconic staircase, will be a popular spot for parties, corporate events, and even weddings.

Belfast is competing with other cities around the world for tourists' Titanic dollars. There's an exhibition at the National Geographic Museum in Washington, a touring artifact exhibit in the United States, and the new Sea City museum in the English port of Southampton, where Titanic picked up passengers and began its final voyage.

Husbands, the CEO, is confident that Titanic Belfast will succeed. He said that 80,000 advance tickets have been sold, and predicted 425,000 visitors in the first year.

Belfast authorities are counting on the attraction to spur a wider regeneration of the city, which has been rebuilding since a 1998 peace accord helped end three decades of sectarian strife.

Part of the challenge is to find new industries to replace vanished trades such as shipbuilding. Harland & Wolff, which once employed 36,000 people in Belfast, now has a work force of just a few hundred who repair ships and build wind turbines.

Later in the year, tourists will be able to visit SS Nomadic, the handsome steamship that ferried passengers to the Titanic during its stop in Cherbourg, France. Previously a floating restaurant beside the Eiffel Tower, it has been brought back to Belfast and is being lovingly restored.