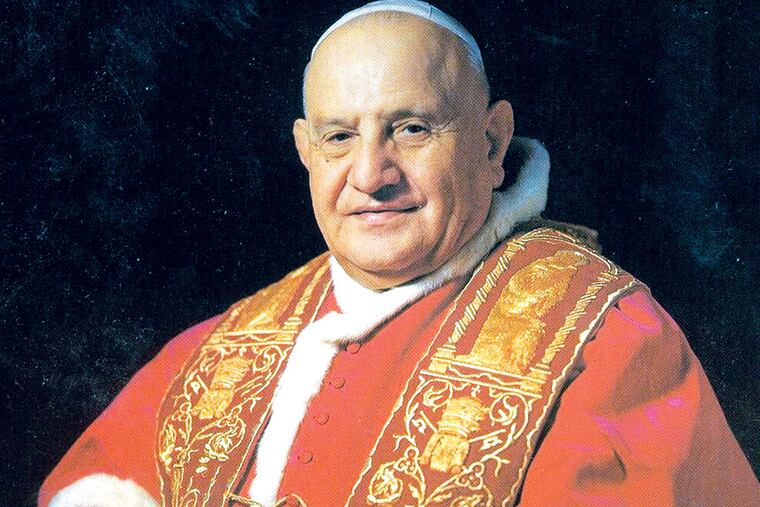

John XXIII opened windows for the church

FULL MOON BATHED ST. PETER'S SQUARE in Vatican City on the night of Oct. 11, 1962, in what many saw as a holy light.

FULL MOON BATHED ST. PETER'S SQUARE in Vatican City on the night of Oct. 11, 1962, in what many saw as a holy light.

Despite the lateness of the hour, the faithful holding candles packed the square and called out to the pope to make an appearance.

Pope John XXIII appeared at the window and delivered what became known as the "Sermon on the Moon."

The occasion was the opening session of the Second Vatican Council, and while not many of those in the square could have perceived the full meaning of what had transpired, a momentous event in the history of the Catholic Church had occurred.

Although John XXIII would not live to see the council's work concluded - he died on June 3, 1963, at age 81 - his vision launched what amounted to a revolution in the ancient religion, the beginning of a movement conceived to bring the church into the modern world.

On that moonlit night in Rome, the pope concluded his remarks by saying, "Returning home, go to your children. Give them a hug and say, 'This is the pope's hug.' Maybe you'll find tears to dry. Say a good word: 'The pope is with us.' "

John XXIII was considered a stopgap pope. Elected at age 76, he was supposed to keep the Chair of St. Peter warm for the next, younger man.

But he had other ideas. There was shock and some dismay when he announced the Second Vatican Council. Cardinal Giovanni Montini, who would become Pope Paul VI, remarked to a friend that "this holy boy doesn't realize what a hornet's nest he's stirring up."

John had been in office less than three months when he announced in January 1959 that the council would convene. In preliminary discussions about its purposes, he insisted that the time had come to "open the windows of the church to let in some fresh air."

Vatican II, as it came to be called, would open those windows. It led to important changes in the church.

For one, the council sought to make the Mass a more vibrant experience for a laity that for centuries had worshipped passively and in near-silence.

The Mass, traditionally celebrated in Latin by the priest standing with his back to the parishioners, would be spoken in the language of the country in which it was celebrated, with the priest facing the worshipers.

The custom of women's wearing hats or head coverings in the church withered away. Suddenly, guitars and drums started replacing or supplementing the old organs.

Nuns' habits became less cumbersome, with some orders dressing their sisters in ordinary clothing.

The council also called for opening dialogue with other religions, and an end to blaming the Jews for the death of Jesus.

Pope Francis, who announced last Sept. 30 his intention to canonize Popes John XXIII and John Paul II in a single ceremony on April 27, described John XXIII as "a bit of a country priest, a priest who loved each of the faithful and knew how to care for them.

"He was holy, patient, had a good sense of humor, and especially, by calling the Second Vatican Council, a man of courage. He was a man who let himself be guided by the Lord."

Lyndon B. Johnson was able to put into a few words the character and accomplishments of John XXIII when he awarded him the Presidential Medal of Freedom posthumously, in December 1963.

The president said John was "a man of simple origins, of simple faith, of simple charity. In this exalted office, he was still the gentle pastor.

"His goodness reached across temporal boundaries to warm the hearts of men of all nations and all faiths."

According to Charles J. Chaput, archbishop of Philadelphia, Pope John XXIII was "a man who committed himself to world peace and international justice.

"In talking about peace, John always began with the rights of the individual human person and the importance of the common good. Peace in the world begins in our own personal actions, and in public forums like Congress and state legislatures.

"We can't protect our own rights unless we defend the rights of the weakest members of our own society."

Angelo Giuseppe Roncalli was the fourth of 14 children born to a family of sharecroppers in a village in Lombardy, Italy. His life before he became pope was one of unceasing service to his faith and people, Catholic and non-Catholic.

He was a sergeant in the Italian army in World War I, in which he served as a stretcher-bearer carrying the wounded on the front lines.

He worked tirelessly to help Jews escape the murderous talons of the Nazis in the 1930s and '40s, and always decried the tendency of the Catholic Church to blame Jews for the crucifixion.

When Roncalli attended the conclave of cardinals in which he was elected pope in October 1958, he had a round-trip train ticket from Venice, where he was the patriarch. After 11 ballots, to his surprise, he was elected pope and didn't need the return ticket.

He became known as il Papa buono, the Good Pope. He visited prisoners and sick children, and was known to slip out of the Vatican at night to take in the sights of Rome. That last habit earned him the nickname "Johnny Walker."

During the Cuban Missile Crisis in October 1962, John offered to mediate between President John F. Kennedy and Soviet leader Nikita S. Khrushchev. Both men thanked him for his offer, and when John XXIII became ill, Khrushchev sent him a note expressing his best wishes. The pope personally typed a letter thanking Khrushchev for his concern.

Time named John its "Man of the Year" for 1962, the first pope to receive the title, followed by John Paul II in 1994 and Francis in 2013.

Angelo Roncalli was ordained a priest on Aug. 10, 1904. He was made a cardinal by Pope Pius XII on Jan. 12, 1953. He served numerous church positions over the years.

John was declared "blessed" in September 2000 by Pope John Paul II, after a miracle of curing an ailing Italian nun was found. Church doctrine holds that two miracles are needed for sainthood, but Francis waived that requirement for John XXIII because of his many good works.

John was diagnosed with stomach cancer in September 1962, and died nine months later.

Two wreaths placed on the sides of his tomb in the Vatican grottoes were donated by the prisoners of Regina Coeli and the Mantova jail in Verona, both of which the pope had visited.

He had told the inmates, "You can't come to me, so I'm coming to you."

They were acts so typical of il Papa buono.