How the 1964 Democratic Convention sank Atlantic City

If you think things are lousy in Atlantic City now, you should have been there 50 years ago this week.

EVEN THE LATE "positive thinking" avatar Norman Vincent Peale would have a tough slog finding optimism over Atlantic City's current state, what with gaming revenues running about half of what they were eight years ago and three casinos set to turn out their lights by mid-September. But everything is relative. Compared with 50 years ago this week, the town is Las Vegas, Paris and Rio de Janeiro combined.

The resort's post-World War II decline was exacerbated by what should have been a triumph: Atlantic City had won the right to host the Democratic National Convention.

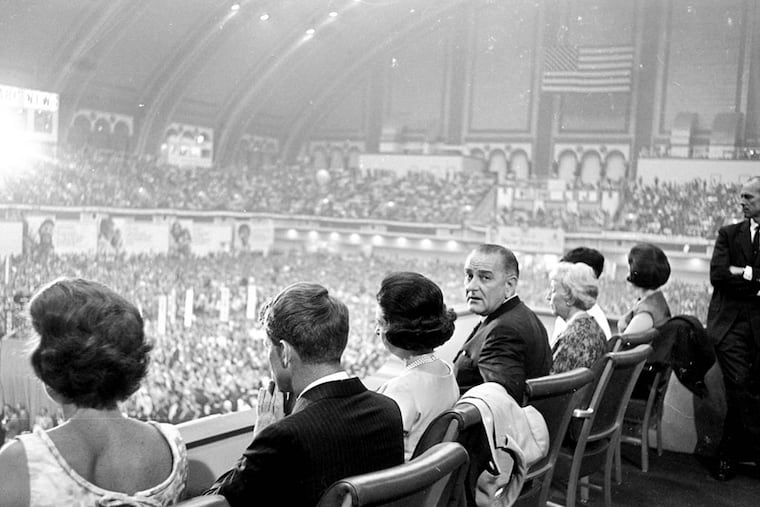

For four days, beginning Aug. 24, the nation's eyes were on the Democrats' nominating convention at what was then called Convention Hall and is today Boardwalk Hall. By the time the final gavel sounded, Atlantic City's decades-long reign as "The World's Playground" was in tatters.

But the pummeling its already-sagging reputation took that week and thereafter would ultimately lead to the city's rebirth.

Delegates and reporters arrived in a town "where the tourism industry was clearly on the decline, with old hotels that didn't have central air conditioning, not every room had a phone, hardly any rooms had a television," explained Nelson Johnson, author of Boardwalk Empire, the 2002 history of Atlantic City that inspired the HBO series of the same name that launches its fifth and final season Sept. 7. "It was a pretty beat place."

Making matters worse, Johnson added, was that the Republicans had convened six weeks earlier in San Francisco, which he described as "a community where the tourist industry was on the rise, with new hotels and a new convention center. The contrast [for the media] was really severe."

But, noted the author in his book, none of this kept local hoteliers and other merchants from gouging their guests, figuring they'd never see them again anyway.

What the locals apparently didn't consider were the thousands of reporters who were thrilled to share their unhappiness and disgust with Atlantic City with their millions of readers, listeners and viewers.

Had the convention itself offered anything resembling intrigue or drama, those covering it might have been too busy to complain about the town's lack-of-hospitality industry. But except for a rumored push by Robert F. Kennedy that, to President Lyndon Johnson's relief, never materialized, and a floor fight over the seating of the all-white Mississippi delegation, the '64 Dem confab was a snooze fest. That gave the press corps plenty of time and space to brood publicly about the conditions they were forced to endure.

Even famed presidential historian Theodore White couldn't resist taking potshots. In The Making of the President, 1964, he wrote, "Of Atlantic City, it may be written: Better it shouldn't have happened . . . time has overtaken it, and it has become one of those sad, gray places of entertainment . . . where the poor and the middle class grasp so hungrily for the first taste of pleasure that the affluent society begins to offer them - and find shoddy instead . . . it is rundown and glamourless."

The Fourth Estate's contempt for the beleaguered seaside town endured for years.

"After the convention, the town got a lot more scrutiny than it wanted, and the political power structure got an examination it didn't want," Nelson Johnson said. "It led up to investigations of corruption and a series of indictments in 1972."

Thanks to the technology that brought middle-class Americans air conditioning and affordable air travel - the same factors that killed the once-bustling Catskills resorts - nails had been hammered into AyCee's coffin for years before 1964.

The convention debacle not only applied the final nail, but lowered the box into the ground. For the next decade-plus, Atlantic City would be little more than Camden with a boardwalk - just another small, decaying northeastern city facing metastasizing poverty and all the ills that it brings: the flight of its middle class, high crime, blight and a palpable sense of despair.

But a few civic-minded die-hards were challenged to seek ways to fix the seemingly unfixable situation. The ultimate solution was both innovative and controversial.

A referendum to sanction casinos throughout New Jersey failed in November 1974; two years later, state voters green-lighted gambling in Atlantic City, which paved the way for a quarter-century of unfettered economic growth (even if the city itself never became the paradise legal gambling's early boosters envisioned).

Today, the city again finds itself facing formidable problems. But even after Sept. 16, when Trump Plaza follows Revel and Showboat down the road to extinction, the Atlantic City that remains will still be more vital, successful and glamorous than anyone could have imagined during that week in late August 1964.

Blog: philly.com/Casinotes