N.J. schools among 'most segregated' in nation, suit says

The lawsuit alleges New Jersey has created and maintained "one of the most segregated public school systems in the nation" and faults the state for requiring students to attend public schools in the municipalities where they live, rather than taking action to reduce segregation.

TRENTON — In a case that could reshape New Jersey's public school system, a coalition of civil rights advocates and black and Latino students sued the state Thursday, alleging that persistent segregation has violated the constitutional rights of hundreds of thousands of students.

Filed by the Latino Action Network, the NAACP New Jersey State Conference, and other plaintiffs, the lawsuit argues that New Jersey has been "complicit" in creating and maintaining "one of the most segregated public school systems in the nation." One white student also joined the suit.

Although the total of black and Latino students is nearly equal to the white total statewide, a significant and growing number of blacks and Latinos attend schools that are almost entirely nonwhite, the suit says. That includes districts that have been under state control.

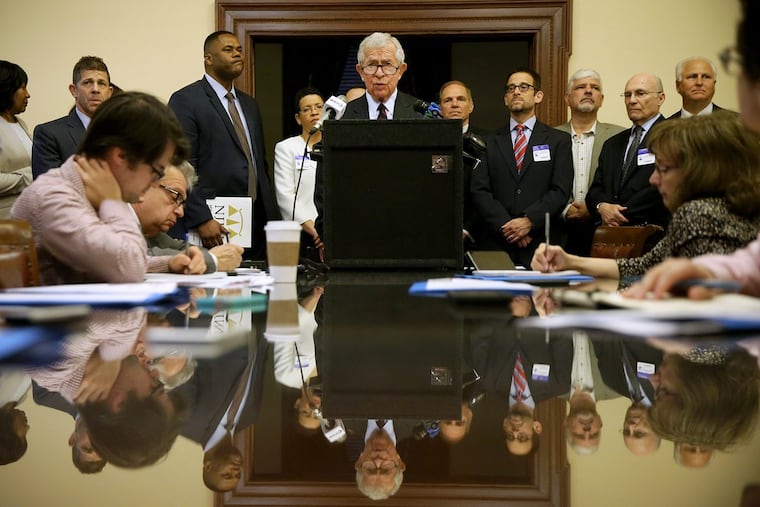

"New Jersey's segregation results from a longstanding failure of state educational policy that's legally and morally indefensible," said former state Supreme Court Justice Gary Stein at a news conference in Trenton announcing the suit. But Stein said the remedies "may take several years to implement."

A spokesman for Gov. Murphy said that while the administration could not comment on pending litigation, Murphy "is deeply committed to boosting diversity in our schools."

The lawsuit faults the state for requiring students to attend public schools in the towns where they live rather than taking steps to reduce segregation, including consolidating its fragmented school districts. It asks the court to declare unconstitutional the state's "longstanding and intensive segregation" of black and Latino students, and require the state and lawmakers to come up with a new methodology for assigning students to schools.

New Jersey might have an exceptionally favorable environment for such a challenge, legal experts say. The state constitution explicitly prohibits segregation in public schools; Pennsylvania's and other states' do not.

In Camden County, the suit names Camden, Lawnside, and Woodlynne as districts with better than 90 percent nonwhite pupil populations, with at least 64 percent living in poverty. More than three-quarters of the pupils in the state-controlled Camden district are enrolled in schools almost absent of whites, according to the suit, which also faults the state for permitting charter schools to locate in "individual intensely segregated urban districts" rather than implementing multi-district schools to promote diversity.

Statewide, the population of New Jersey public school students in 2016-17 was 45 percent white, 27 percent Latino, 15.5 percent black and 10 percent Asian.

"Because educational opportunity is, as a result, undermined for students in schools that are often characterized by intense poverty and social isolation in numerous, well-documented ways, these segregative state laws, policies, and practices deny an alarming number of black and Latino students the benefits of a thorough and efficient education," the lawsuit alleges.

It also contends that all pupils, "including white students," are harmed by "homogeneous learning and social environments" that "produce a two-way system of racial stereotyping, stigma, fear, and hostility that obscures individuality and denies all concerned the recognized benefits of diversity in education."

The case "is going to be extremely important in reinspiring state advocates to use their state constitutions to promote school integration," said Philip Tegeler, a civil rights lawyer in Washington. But it was not clear just how the case might apply elsewhere.

The lawsuit, announced on the 64th anniversary of the U.S. Supreme Court's Brown v. Board of Education decision that declared government-mandated segregation to be unconstitutional, was filed in Superior Court.

That anti-segregation provision in its constitution provides a stronger basis for a desegregation case than federal law, legal experts say. And unlike at the federal level, New Jersey's court has also ruled that the state has the power to order school districts to consolidate to achieve racial balance.

"The two big obstacles to national integration were both eliminated almost half a century ago" in New Jersey, said Paul Tractenberg, a former Rutgers University law professor who leads a nonprofit focused on diversity and equality in education.

New Jersey's many school districts — 674, most confined to town boundaries and including 40 percent that don't serve students in all K-12 grades — combined with the requirement that students attend school where they live "is really a recipe for segregation," said Tegeler, a member of the steering committee for the National Coalition on School Diversity.

The proportion of students in New Jersey attending schools that are less than 10 percent white has risen "almost continuously" since 1990, according to a report by Tractenberg. The percentage of schools enrolling less than 10 percent white students has more than doubled since the 1989-90 school year.

Those schools performed worse than state averages, the report said. It found "a significant correlation between how proportional a school's demographic profile is to the state and an array of educational outcomes," including graduation, dropout and college matriculation rates.

Research has proved the benefits of integration, including exposure to students with more resources, said Gary Orfield, research professor and co-director of the Civil Rights Project at UCLA.

"It's very hard to get ready for college in a school where almost everybody is nonwhite, and almost everybody is poor," Orfield said. Integration "makes a big difference not just for your education, but for your life."

The suit alleges that New Jersey has ignored "feasible solutions" to segregation, including letting black and Latino students attend schools outside their home districts and the creation of themed magnet schools to attract students across a region.

"New Jersey needs this lawsuit. … There's no amount of goodwill or well wishes or optimism we can marshal that will accomplish the kind of systemic relief … that is required," said Ryan Haygood, president of the New Jersey Institute for Social Justice.

But the issue underlying the lawsuit isn't just where students are permitted to attend public school, but where they live.

"One of the issues that will undoubtedly arise is, school segregation is in at least some part the result of housing segregation," said Dennis Parker, who is director of the ACLU's Racial Justice Program and has been involved in a long-running Connecticut desegregation case. "How that plays into what created the problem and how you remedy it is important."

New Jersey municipalities and school districts long have resisted consolidation. "One of the things that has kept this from being part of the policy debate in New Jersey is the concept of home rule, where politicians have been really afraid to take it on. It has a lot of consequences," including high property taxes and schools that are segregated, "because they're so community-based," said Patrick Murray, director of the Monmouth University Polling Institute.

While advocates won landmark school funding rulings intended to equalize aid between rich and poor districts, "we did not try to deal with the fact that the poor, urban districts are overwhelmingly populated by low-income, minority kids," said Tractenberg, who founded the Education Law Center that brought the Abbott v. Burke case.

New Jersey's growing diversity — 45 percent white students last year, down from 52 percent in 2010-11 — has produced some "surprisingly diverse" school districts, Tractenberg said. But that diversity isn't necessarily present at the school or classroom level, he said — another challenge in bringing about integration.

As the nation becomes increasingly nonwhite and the percentage of students in poverty grows, "the educational consequences for the kids who are isolated increase," Orfield said. And white students who are isolated "are going to be severely unprepared for the society they're going to be living in as adults."

This article was corrected to reflect that New Jersey's population is 55.8 percent white, according to the U.S. Census.