New Jersey's Teacher of the Year among finalists for national teaching honor

Ocean City High School's Amy Andersen is the second in the state to make the final round for the award.

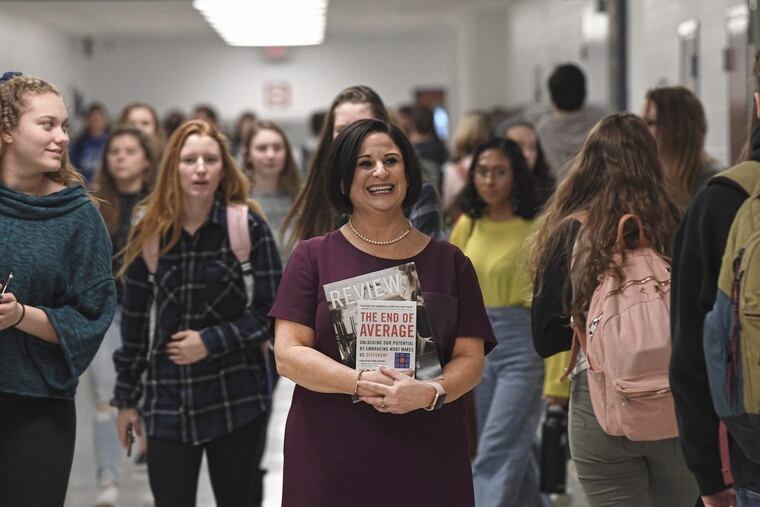

When American Sign language teacher Amy T. Andersen steps into a classroom, she immediately commands attention from her students.

An educator for more than two decades, Andersen has carved a niche at Ocean City High School in Cape May County, where students eagerly fill up every spot in her popular classes. Now she hopes to take her passion to a national arena to share her experiences that extend beyond the classroom to the deaf community.

"The most important thing you can do as a teacher is connect with your students," she says. "If you feel that a teacher loves you, that's the name of the game."

Andersen, 45, is among four finalists for National Teacher of the Year. It is the first time since 1972 that a New Jersey educator has been considered. The finalists were chosen by a national selection committee of the Council of Chief State School Officers from a field that included all 50 states and U.S. territories. The other finalists represent Ohio, Washington State and the Department of Defense Education Activity at Camp Lejeune in Jacksonville, N.C.

The winner will be announced this spring in Washington, D.C. The recipient will spend the next year on sabbatical traveling the country as an education advocate, giving speeches to policymakers and working with other educators. The award has been given by the council, a national nonprofit organization, since 1952. New Jersey has participated since 1969.

Andersen was named New Jersey's Teacher of the Year for the 2017-18 school year last October. She was selected from a field of seven other county finalists for the top honor to advance to the national competition.

"She's by far not only my favorite teacher but the best teacher I've had in my entire life," said Tim Smith, 16, a junior and second-year sign language student. "She's just so much more than a teacher."

Andersen started the American Sign Language program at Ocean City High in 2004 with 42 hearing students; today about 130 students are enrolled in six classes. More than 85 percent of her students have obtained the state seal of biliteracy in sign language. The high school has 1,200 students.

Many of her former students have studied American Sign Language in college and landed jobs as interpreters and deaf educators. Some have interpreted for former First Lady Michelle Obama and Madonna.

Outside of school, Andersen has helped transform Ocean City into what locals describe as a deaf-friendly community. The library offers sign language classes that have become popular among parents. Former students work in stores, restaurants and businesses and readily provide sign language services, if needed. There also socials at local coffee shops for students to interact with the deaf community and evening performances to raise funds for scholarships to benefit her students.

Anderson volunteers at a local day care center, where she works with deaf and hearing-impaired infants and toddlers. She convinced the state, believed to be for the first time ever, to hire a deaf paraprofessional to work with a young deaf boy who was lagging because he lacked communication skills.

Every year, more than 12,000 babies are born with hearing loss, according to the Alexander Graham Bell Association for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing.

"I want that for all babies," said Andersen, a mother of two, Jacob, 6 and Jordan, 13. She will spend six months working with the state Department of Education on a policy project to expand services to deaf and hearing-impaired infants and toddlers.

She has been on sabbatical from teaching since January, providing professional development to other teachers across the state, and attending workshops. She has logged nearly 9,000 miles on the 2017 Ford Fusion she received as state Teacher of the Year.

Andersen returned to Ocean City High last week for a reunion with her students and staff. She met with student leaders during a lunch meeting to brainstorm on how to create a more inclusive environment where students can celebrate their differences.

"I miss my students a lot," she acknowledged. "It's bittersweet being out of the classroom."

Andersen visited with her second-year sign language class during the final period of the school day. The school hired two co-teachers to fill in for Andersen. The students were obviously excited to see Andersen, but following protocol, silence prevailed in the classroom, where only sign language is used to communicate.

Standing before her students, Andersen relished her role, jumping into the lesson and dividing the class into groups. A few times, laughter erupted when Andersen made a witty comment. She flicked the lights to get their attention.

"Mrs. Andersen is amazing," Sarah Zigner, 16, a junior, said in an interview in the library.

Zigner said the sign language class has made her more confident, improved her public speaking skills and helped her make friends. Once an aspiring doctor, Zigner said she now plans to either follow in Andersen's footsteps or teach deaf or hearing-impaired students.

Senior Elizabeth Buch, 18, an aspiring actress, said she plans to major in theater and deaf education after she "stumbled" upon Andersen's class her sophomore year. "She's just so warm and welcoming. She still loves what she does."

During the 2016-17 school year, 2,689 high school students statewide took American Sign Language, state officials said. Nearly three dozen districts offer the course as a world language.

Andersen, an only child, grew up in Cape May County. Her parents were both special education teachers and later, administrators. But she wanted to be a musician. That changed while she was attending Indiana University and enrolled in an American Sign Language class, got involved in the deaf community, and volunteered in a kindergarten class for deaf students.

She began her teaching career in 1996 in Boston, where she worked for eight years. One of her former third-grade students, Sam Harris, became a sign language expert and became a media star when his expressive hurricane warning translations for Florida Gov. Rick Scott made headlines. He later made an appearance on Jimmy Kimmel.

Harris, 32, an American Sign Language professor at St. Petersburg College in Clearwater, Fla., said Andersen took him under her wings during a difficult period in his young life. She shifted his "focus from negative to positive," he said.

"She was a good teacher. I learned a lot," Harris recalled in an interview. "She's part of the reason I am who I am."

Andersen said her status as state Teacher of the Year has given her a rare forum to advocate for children and the profession, and that makes her a winner.

"I don't need my face on a magazine or all of the accolades," she said. "It's put me in a position where my voice is heard."