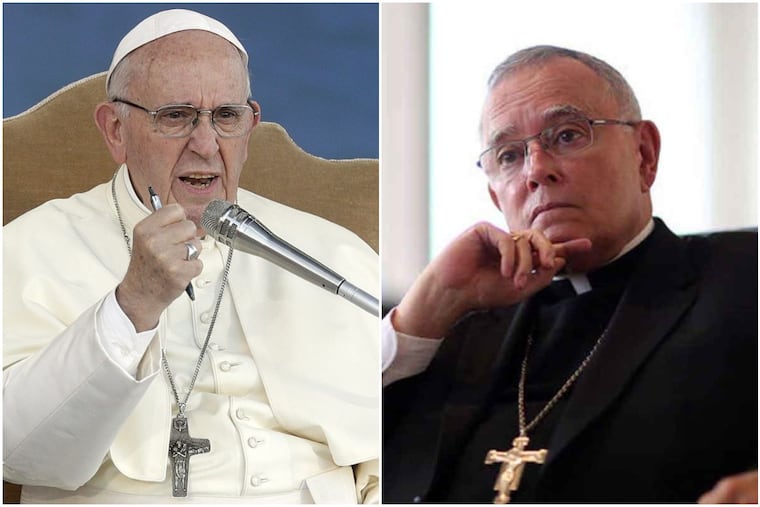

For Archbishop Chaput and Pope Francis, envoy’s letter a reminder of past tensions

Pope Francis' purported reproach of the region's top Catholic as too "right-wing" underscored a widening rift between the church hierarchy's conservative and liberal wings.

It's a rare papal slight that receives a public airing — and this one was aimed directly at Philadelphia's Archbishop Charles J. Chaput.

But Pope Francis' purported reproach of the region's top Catholic as too "right-wing" — as stated this weekend in a public letter penned by one of the pontiff's most vocal critics — offered more than just an unusual glimpse into the Vatican's dirty laundry.

It underscored a widening rift between the church hierarchy's conservative and liberal wings, and suggested evidence of a flinty relationship between two men who may best epitomize both sides.

In public, Chaput, an unswerving traditionalist, and Francis, embraced by liberals as a Vatican "change agent," have professed mutual admiration — most notably as the two stood side by side during the pope's visit to Philadelphia in 2015.

And yet their public pronouncements have put them at apparent odds on issues ranging from same-sex relationships to divorce and the church's role in politics.

The perception of a split between the men has so often garnered attention that Chaput complained to the Washington Post in 2015 about the tendency to pit him as Francis' foil.

It "is a great narrative," he said, "except that it's not true."

Yet Saturday brought more confirmation of a divide.

In a published letter, the Vatican's former top diplomat to the United States, Archbishop Carlo Maria Viganò, a staunch Francis critic, called on the pontiff to resign, alleging that he and his predecessor, Benedict XVI, had long known about the sexual misconduct of Cardinal Theodore McCarrick, the former archbishop of Washington, who was forced to step down this summer amid scandal.

In an unrelated passage tucked into the 7,000-word memo, Viganò recounted a five-year-old exchange in which Francis allegedly took a swipe at Chaput.

"The bishops in the United States must not be ideologized," Viganò said Francis told him at a 2013 gathering of papal ambassadors in Rome. "They must not be right-wing, like the archbishop of Philadelphia."

Viganò wrote that Francis also said bishops should "not be left-wing" either, adding, "And when I say left-wing, I mean homosexual."

Francis has not denied Viganò's characterization of his remarks. He sidestepped questions from reporters aboard the papal plane Sunday as he was returning from Ireland, saying he would not dignify the former diplomat's letter with a response.

"I will not say a single word about this," he said. "I believe the statement speaks for itself."

Chaput, meanwhile, declined to respond directly, saying through a spokesperson that Viganò's claims were "beyond his personal experience." But he vouched for the former ambassador's character, saying he "found his service to be marked by integrity to the church."

Those words might hardly seem inflammatory to most lay people, but longtime Catholic Church observers saw hints of palace intrigue.

"We know that Archbishop Chaput had words of praise for Bishop Viganò," said Massimo Faggioli, a theology professor at Villanova University. "And that is surprising, given that Viganò put pressure on the pope to resign. One would expect a bishop to say that no one has the right to ask the pope to resign."

Chaput and the pontiff first met at 1997's Synod for Bishops for America in Rome, when Francis was Archbishop Jorge Bergoglio of Buenos Aires. The paths their careers have taken since have increasingly put them at odds, at least in tone if not on issues of doctrine.

Both men, observers say, view the Catholic Church as at a crossroads. They differ on which path to take.

Francis, since his election in 2013, has warned church leaders away from engaging in politics, and advocated opening the Catholic tent to better engage with a changing world — a vision perhaps best crystallized by his response to reporters' questions that same year on his views about participation by homosexuals in the church.

"Who am I to judge?" the pontiff replied.

Chaput, meanwhile, has emerged as one of conservative Catholicism's leading voices in America — an unapologetic culture warrior who has thrown himself into political debates on same-sex marriage and abortion with relish, strongly arguing against both. From the pulpit, he has advocated for strict adherence to traditional doctrine, fearing that accepting loosening public mores without a fight could set the church irrevocably adrift.

"Stuffing your Catholic faith in a closet when we enter the public square or join a public debate isn't good manners," he told a room full of Catholic lawyers in Harrisburg in 2006. "It's cowardice."

Despite their differences in approach, Chaput has never publicly criticized the pontiff and has said they agree on fundamental church teachings against gay marriage, abortion, euthanasia and contraception.

In a 2013 interview with the National Catholic Reporter, he said the pope's seemingly more permissive statements have been misinterpreted by people who "want to use [him] to further their own agendas."

And yet, Chaput's approach and Francis' vision have appeared at times to be at directly odds.

For instance, when Francis in 2016 issued a pronouncement that appeared to give bishops more latitude in deciding whether to give Holy Communion to divorcees or those in same-sex relationships, Chaput four months later issued a decree insisting that Catholics in "irregular" sexual relationships should still be denied within the Philadelphia Archdiocese.

Two years prior, when the pope convened a meeting in Rome to encourage more open debate on the church's stances on controversial social issues, Chaput, in public remarks, worried that it left an impression of uncertainty. "I think confusion is of the devil," he said.

Some church watchers cited that apparent difference in worldviews to explain Francis' passing over Chaput when he named 17 new American cardinals in 2016. The five previous archbishops serving the Philadelphia Archdiocese had all been elevated to cardinal.

For all the public discussion of their differences, Philip Cunningham, a theology professor at St. Joseph's University, said he sees the divide as more one of style than substance.

"Chaput's way of doing theology and relating to the traditions is with a different style, and with a different set of priorities, than the pope," he said. "They're not mutually exclusive by any means, but they are different."